The evidence is in: Protests can persuade people, and maybe even change how they vote.

An estimated 5 million people around the world took to the streets last weekend in the largest show of resistance yet to President Donald Trump’s return to the White House.

The “Hands Off!” protesters expressed outrage over Elon Musk’s dismantling of federal agencies and programs through the so-called Department of Government Efficiency, the mass firing of federal workers, and attacks on the rights of immigrants and trans people. Two-thirds of attendees at the Hands Off rally in Washington, D.C. — which drew an estimated 100,000 people, according to organizers — named climate change as one of their top motivations for participating. That’s according to data from Dana Fisher, a sociologist at American University whose team surveyed the protesters.

The protests were peaceful, with marchers sticking to preapproved routes and refraining from the kind of civil disobedience that can lead to arrest. That’s in contrast to the array of new tactics the climate movement has implemented in recent years, from the disruptive (blocking roads) to the just plain weird (throwing tomato soup at the glass in front of a Vincent van Gogh painting). These tactics are often unpopular, raising concerns about backlash. But there’s mounting evidence that they work — especially in tandem with more mainstream efforts.

A new review of 50 recent studies finds that protests tend to sway media coverage and public opinion toward the climate cause, without appearing to backfire, even when disruptive tactics are used. The researchers, from the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication, found that collective action sometimes influenced elections by shifting people’s voting behavior. One study in Germany, for example, found that the Green Party received a larger portion of the vote in areas where climate protests took place.

“People only have so much stamina and attention and will to keep fighting in the face of insurmountable odds,” said Laura Thomas-Walters, a co-author of the review and an activist with Extinction Rebellion UK “Let’s use it as effectively as possible.” Thomas-Walters argues that disruption should be aimed at institutions that prop up the status quo, such as banks, corporations, universities and pension funds, to influence decision-makers.

Her review found real-life evidence of the “radical flank effect,” the idea that a more extreme climate group can increase support for more mainstream groups. Two weeks after the group Just Stop Oil blocked a major road around London in November 2022, the public’s support increased for a more moderate group, Friends of the Earth, according to a study published last fall. “You know, it’s ultimately like a good-cop, bad-cop approach,” said James Ozden, a co-author of that study and the founder of the Social Change Lab in London, which conducts research on the effects of protests.

Last month, Just Stop Oil announced that it was ending its three-year resistance campaign, claiming it had achieved its demand of ending new oil and gas licenses in the United Kingdom. But that success came with a cost: dozens of the group’s protesters have faced jail time. According to Fisher, who has been studying climate activism for two and a half decades, that’s not a fluke. “Activists are met with repression when their activism is starting to resonate and work,” she said.

Lab Ky Mo / SOPA Images / LightRocket via Getty Images

Climate protests might even lead to reductions in emissions, the review found, though these effects are hard to study and the evidence is still limited. For instance, parts of the U.S. with lower levels of protests during the initial Earth Day in 1970 had higher levels of air pollution 20 years later compared to places that had better turnout. More recently, a wildly unpopular campaign called Insulate Britain, which blocked roads and demanded that the government retrofit all homes in the United Kingdom, eventually got some of what it wanted, with former prime minister Boris Johnson drawing up plans to insulate thousands of homes in 2022.

There are questions, however, about how these results apply to the rapidly changing political environment in the U.S. in the nearly three months since Trump took office. “The political stakes for protest, and the risks around protest as well as the tactics that will work and won’t work, are changing quite substantially,” Fisher said.

Organizers have recently been inspired by research that looks at efforts in other countries to counter authoritarianism, said Saul Levin, the director of campaigns and politics at the Green New Deal Network, a coalition of climate, labor, and justice organizations. He pointed to a paper from last year, which has not yet been peer-reviewed, that found that a democracy has a substantially higher chance of surviving a political push toward autocracy when there’s a strong public resistance. Based on 35 case studies in countries around the world since 1991, the authors found that there was an 8 percent chance of democracy persisting when there was no active anti-authoritarian movement, compared to a 52 percent chance when an active movement existed.

to solve climate change, we need to harness the power of the federal government

Through surveys of protesters, Fisher has found that climate activists want to remain peaceful, even as she’s seen an alarming increase in support for political violence among left-leaning activists generally. “I do think that it is important to remember that some of the most effective movements that we’ve seen in the United States, as well as globally, have been movements that embrace and commit to peaceful resistance,” Fisher said. “That being said, one of the reasons that those movements have been so successful is because they were met with repression and violence from the state.” In many cases, attempts to repress protests actually fuel resistance and mobilize people.

Levin sees the pro-democracy protest movement as inseparable from the fight for climate action. The Trump administration has cut programs to protect clean air and water and respond to weather disasters. Just this week, Trump signed an executive order instructing the Department of Justice to stop the enforcement of state-level climate laws.

“The whole idea of the Green New Deal,” Levin said, “was that to solve climate change, we need to harness the power of the federal government. They’re destroying the federal government. So inherent to the success of solving climate change is defending these institutions.”

PEER-REVIEWED ARTICLE · Mar 27, 2025

The impacts of climate activism

By Laura Thomas-Walters, Eric Scheuch, Abby Ong and Matthew Goldberg

Filed under: Behaviors & Actions

We are pleased to announce the publication of a new article, “The impacts of climate activism” in the journal Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences.

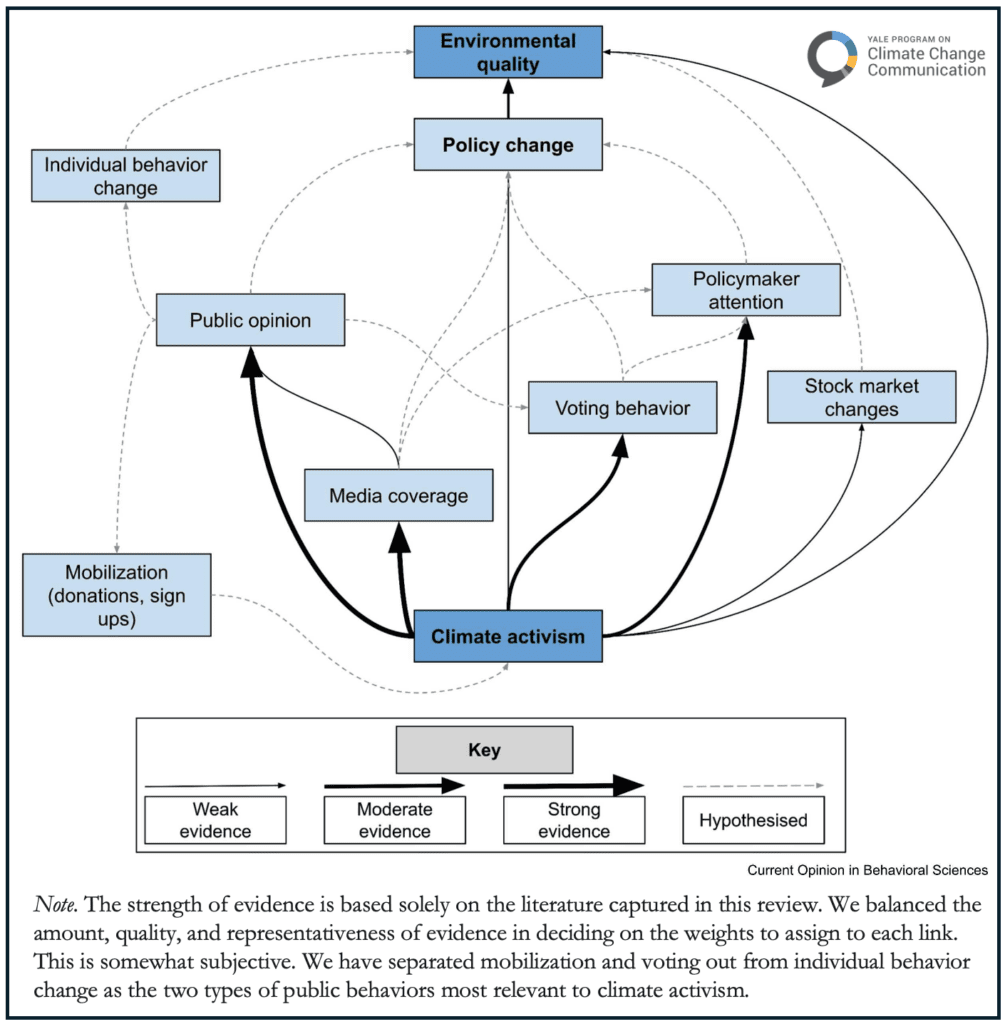

In this article, the research team reviews and synthesizes 50 research articles from the last few years that examine the question: what are the impacts of climate activism? Because climate activism has many different goals and outcomes, the team organized the scientific literature into different outcomes, focusing on impacts on the public, the media, the political system, and other outcomes (e.g., stock market). They took a broad view of what counts as climate activism (e.g., protests, divestment, non-violent civil disobedience), although most studies focused on protests and marches. They focus on collective forms of climate activism, rather than individual actions such as consumer choices or voting behavior. The strength of the evidence for each outcome is summarized in the figure below.

The review finds strong evidence that climate activism influences public opinion and media coverage, although the specific relationship depends on the kind of actions taken and the way the media covers the events. The evidence shows that protest usually increases support for the movement when protests are peaceful, but not when they are violent. But there was also evidence that the influence of activism on public perceptions could be positive or negative, depending on the tone of the media coverage of the protests.

The review found moderate evidence that climate activism can influence voting behavior and policymaker attention. One study in Germany found that areas that experienced Fridays for Future protests had a higher share of the vote go to the Green Party, and that repeated protests increased the effect. Multiple studies in the UK found that protests successfully increase communications by policymakers about climate change or pro-climate actions.

There was less evidence that climate activism leads directly to policy change or improvements in environmental quality. This is not necessarily because climate activism does not affect these outcomes or others we reviewed—it is likely because studies that capture these outcomes are difficult to conduct.

The full article with many other results is available here to those with a subscription to Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences. If you would like to request a copy of the published paper, please send an email to climatechange@yale.edu with the subject line: Request climate activism paper. Or, a preprint version is available here.