Everything you need to know about Australia’s new home battery subsidy

From eligibility to cost, here’s how households and businesses can take advantage of the cheaper home batteries program

Royce Kurmelovs Sat 17 May 2025 in The Guardian

It’s not an overstatement to say Australians love solar power. Without batteries, though, households have struggled to take full advantage of their rooftop systems. Either they don’t capture all the energy produced during the day or they lose their power when the grid goes down. Now the Australian government is looking to fix that with its cheaper home batteries program, which will come into effect from 1 July.

Here’s everything you need to know.

If you have a solar system and battery, you can bank power generated during the day when it is free and use it at night

How will the subsidy work?

The $2.3bn plan will subsidise the installation of small batteries for households, businesses and community facilities. It will be available to households with existing systems and those looking to get solar, and will not be means tested.

It will be available to households with existing systems and those looking to get solar, and will not be means tested.

The scheme is modelled on the subsidy used to encourage the introduction of rooftop solar and will similarly be phased out over the next decade. Households aren’t expected to feel this change because the price of a home battery is expected to drop sharply, as happened with solar.

The Smart Energy Council’s chief executive, John Grimes, says those looking to install a home battery will get a discount of at least 30% on the retail and installation cost – though this is a “rule of thumb”.

a discount of at least 30% on the retail and installation cost

“There’s actually a dollar figure attached to this, so it could be more,” Grimes says. “The way the rebate is structured is that it’s a one-time deal, whether you buy a small battery or big battery, but the rebate is larger for a bigger battery.”

The discount will apply to batteries up to 50kWh; someone buying a 100kWh battery will still get the subsidy on the first half of their installed capacity.

Why is the government offering this?

Tristan Edis from Green Energy Markets says there are two main problems the government is working to solve. The first is that Australians generate heaps of power during the day but there is no way to store for use at other times. The other is that even though the technology is developing fast, the cost of batteries has not come down as manufacturers have not prioritised the residential market. This policy seeks to address both and, long-term, it will enable a phase-out of oil, gas and coal in the power grid.

“First and foremost, it will reduce household power bills, not just for the person installing the battery but other consumers,” Edis says.

“In the longer term it’s also reducing the revenue that a coal or gas generator is able to capture over a full 24-hour period. That will bring forward the date at which they are likely to close.”

What are the benefits?

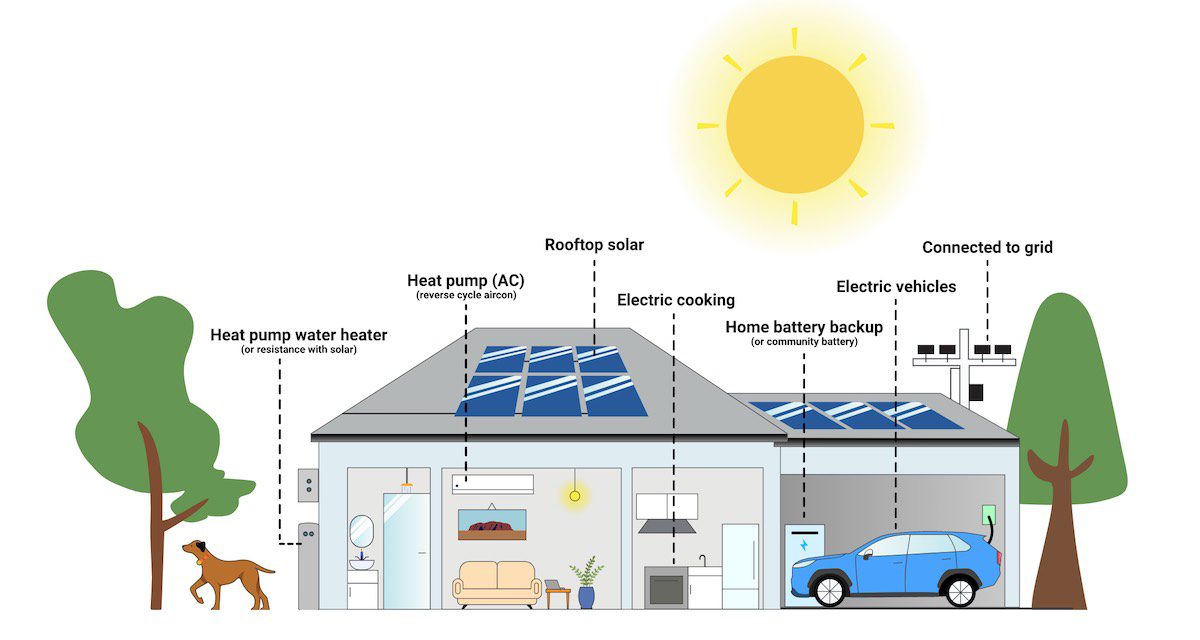

Emissions reductions aside, this will save you money. Grimes describes a battery as acting like a rainwater tank: if you have a solar system, you can bank power generated during the day when it is free and use it at night when it would be more expensive.

According to Labor’s modelling, this will knock $1,100 extra off household power bills each year, or $2,300 a year for those with newer systems – but this is a guide and may vary based on your circumstances.

When can I get a subsidised battery?

Now, effectively. The subsidy comes into effect from 1 July but Grimes says many installers are able to set up a system tomorrow but only turn it on after the start date to ensure you get the discount.

How much will it cost me?

The Smart Energy Council surveyed 9,500 energy users and found a 5kWh to 6kWh battery will cover nine out of 10 households. The price for a battery that size ranges from $5,000 to $9,000 – though there could be other costs if an older solar system needs a retrofit to accommodate a battery.

Getting an entirely new solar array and battery setup is much pricier, with systems starting well above $15,000. Some companies will charge $26,000 before subsidies for large “future-proofed” systems.

Remember, your power bills will be near zero for the lifetime of the system and you will not be paying for fuel if paired with an electric vehicle. State subsidies are also available to further reduce the price on top of the federal rebate.

What kind of battery should I buy?

For some people, a smaller battery will suit their needs but a bigger one may be a good idea to take full advantage of the subsidy.

Every home is different and how much capacity you may need comes down to questions such as: are you on the grid? Is your region prone to blackouts or other natural disasters? What stage of life are you in? Do you work from home? Do you work nights or from nine to five? Do you drive an EV? Does that EV have vehicle-to-grid capacity? If it does, will it be parked most of the day at work when your solar array is producing the bulk of its free power? And, ultimately: what can you afford right now?

There are lots of numbers involved when it comes to the 77 different battery systems on the Australian market. It is also possible a rush in demand will prompt a number of fly-by-night operators to appear, so it is strongly advised to do your research on the company and the system it is offering and to ask around for the best deal.

Households to be “driving force” of energy transition with solar, batteries and EVs

How to fully electrify our homes. Source: Rewiring Australia

Jun 26, 2024

in Renew Economy ELECTRIC VEHICLES

Australian households – and the rooftop solar panels, batteries and electric vehicles they choose to buy and install – are now being recognised as a major driving force of the country’s green energy transition by the Australian Energy Market Operator.

The final version of the latest of AEMO’s 25-year planning blueprints, known as the 2024 Integrated System Plan, notes the huge scale of investments likely to be made by households and other consumers over the coming decades, changing the fundamental nature of the grid.

Some of the numbers are quite breathtaking.

Rooftop solar is expected to grow four-fold from more than 21 gigawatts now to 86 GW in 2050 and home batteries are expected to grow from just 1 GW now to an estimated 7 GW in 2029-30, and 34 GW in 2049-50.

EV ownership is expected to surge from the late 2020s – driven by falling costs, greater model choice and availability, and more charging infrastructure and by 2050 – according to the step change scenario, 97 per cent of all vehicles on the roads are expected to be full battery electric vehicles.

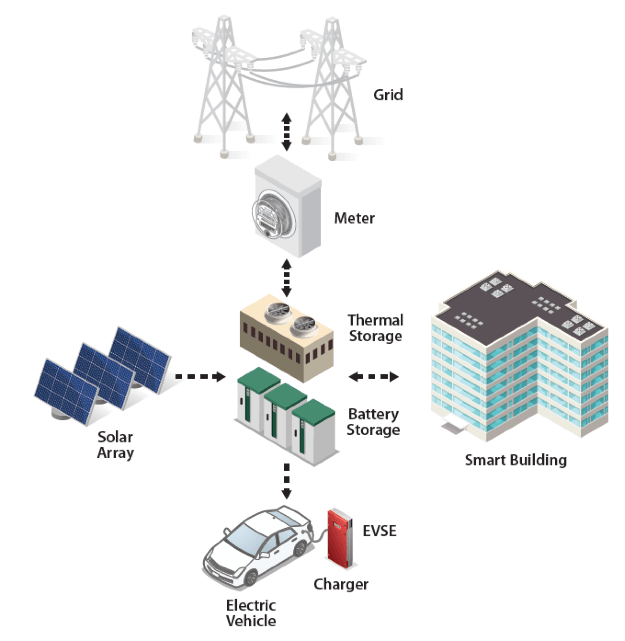

The crucial challenge for AEMO is to get “visibility” and to extent control over these assets because of their scale and their importance to the grid, particularly in their ability to vary demand and provide storage and other grid services at crucial times.

AEMO says that if these assets can be “well coordinated” they can deliver significant savings and, in the case of home batteries alone, will avoid $4.1 billion in costs for additional grid-scale investment in storage.

“Consumers are already a driving force in Australia’s energy transition and this is set to continue,” AEMO chief executive Daniel Westerman says.

“If consumer devices like solar panels, batteries and electric vehicles are enabled to actively participate in the energy system, then this will result in lower costs for all consumers.”

AEMO says other assets such as community batteries, household hot water and pool pumps are expected to also have the ‘smarts’ to help manage the import and export of electricity to the distribution grid.

“Achieving these savings depends on a mix of financial incentives, technology and communication standards, customer preferences, and market or policy arrangements – and in turn increased engagement between consumers, retailers, networks and other market participants,” the document says.

Some of this will be achieved through virtual power plants (VPPs), although AEMO says consumers who own these systems must be able to choose how they are used.

“They will need transparency and material benefits to ensure they support, with confidence, their systems being coordinated with the power system.”

The ISP notes that household energy use is almost entirely made up from lighting and various appliances, but total consumption is expected to triple in coming decades as they use more electricity for heating, cooling and cooking, and to charge their electric vehicles.

That will take total consumption to 150 terawatt hours (TWh) by 2050, but more than two thirds of this will be offset by more rooftop solar, energy efficient buildings and appliances, and changes in behaviour, which will reduce reliance on the grid back down to around 50 TWh, about where it is today.”

Households can draw electricity either direct from their rooftop solar, from the grid, from their household or community batteries, or even from EVs that are able to discharge their batteries,” the document says.

AEMO has ramped up its interested in CER, under pressure from many analysts and lobby groups, and is rapidly shifting its approach from a problem that needs to be solved – it wants visibility and some control over these assets – to an opportunity to accelerate the energy transition.

“While we are pleased the Final ISP contains greater consideration and quantification of the role of consumer energy contributions, bringing together rooftop PV, Behind the Meter storage and EVs, it is critical to ensure consumers are in control of their assets to reduce their bills and build trust,” said Stephanie Bashir of Nexa Advisory.

“It is important now that further work is undertaken to enable these energy resources to support the transition by rewarding consumers for their participation, not penalising them.”

Giles Parkinson is founder and editor of Renew Economy, and of its sister sites One Step Off The Grid and the EV-focused The Driven. He is the co-host of the weekly Energy Insiders Podcast. Giles has been a journalist for more than 40 years and is a former deputy editor of the Australian Financial Review. You can find him on LinkedIn and on Twitter.