How local villagers practice conservation for a fraction of the cost of outside efforts

Guarding lakes and forests from poachers, local communities in Brazil deliver massive conservation benefits—at less than $1 per hectare.

September 24, 2025

Celebrities like Leonardo DiCaprio, Madonna and Jennifer Lopez have made headlines calling for protection of the Amazon rainforest. But anonymous local villagers are the ones playing an outsized role in protecting the forest and wildlife there.

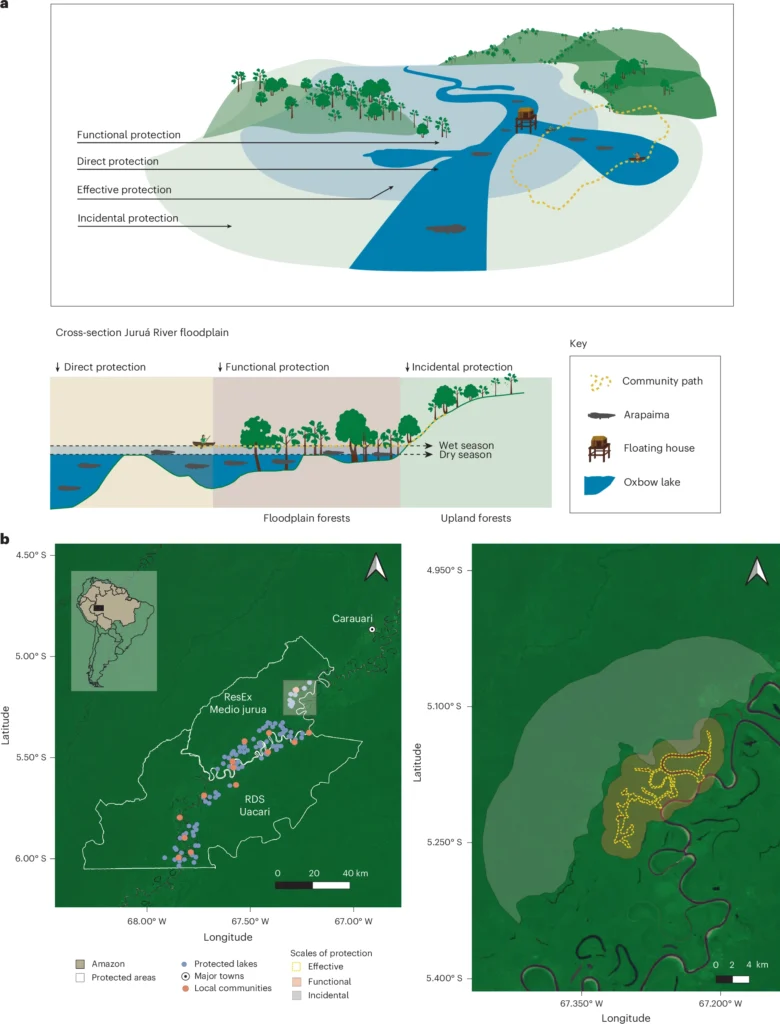

Armed with little more than shotguns and round-the-clock vigilance, people living in 13 small fishing villages scattered along the Juruá River in western Brazil are effectively shielding around 3400 square kilometers of river and forest from poachers and loggers, an area bigger than the state of Maryland, according to new research appearing in Nature Sustainability.

“The conservation dividends from community-based protection are unprecedented and deployed at a tiny fraction of the financial costs of traditional protection mechanisms,” said Carlos Peres, an ecologist at the University of East Anglia in the United Kingdom. “In practice, this makes local land managers true ‘unsung heroes’.”

The new research is the latest in a growing body of work by Peres and colleagues documenting the Juruá as a prime example of how local communities can play a key role in protecting the surrounding lands and wildlife.

Starting in the 1990s, the Brazilian government created reserves along parts of the river where local communities have an official role in managing the landscape. The crown jewel of the effort is a fish known as pirarucu or arapaima. This apex predator is the world’s largest scaled freshwater fish, growing to lengths of more than 3 meters and weighing more than 220 kilograms. Its size and tasty meat make it a central part of the economy of local communities and a target for poachers.

The fish breed in lakes formed when the river recedes after flooding. Some of the lakes are open to all fishing, while others are limited to subsistence fishing or protected from almost all fishing except for a brief, controlled harvest. To enforce these restrictions, people from nearby villages are stationed full time in a floating guard post at the main entrance to each lake.

The system has been a success on several levels. Protected lakes contained around 30 times more fish than lakes open to all fishing, a difference of 304 fish to 10 fish in a lake, according to a 2016 paper. The healthier fish populations also translated into a yearly income boost of around $1000 per household in local villages, the scientists found.

The new research shows those benefits extend well beyond the lakes’ shores. The scientists began with the footprints of 96 lakes guarded by 14 villages, each containing an average of around 13 families. The lakes were typically 47 hectares. But when someone was guarding a lake, their presence also affected activity in the surrounding floodplain, both because they policed activities there and because the higher numbers of fish meant the flooded ecosystem was more intact. The guards also cut off access for people who might want to log the surrounding forests, because waterways act as the main transportation system. In one case, the scientists report, fishers and local leaders worked together to chase away illegal gold miners.

All told, this meant a handful of villages was helping to preserve a large chunk of the landscape, at a time when the Amazon is under immense pressure from mining, logging and farming.

“This study clearly demonstrates the effectiveness of empowering local management action by stakeholders who have the greatest interest and a 24-7, year-round presence where conservation battles are being won or lost,” said Peres.

And the villagers are doing it largely for free, serving as volunteer guards. It’s an arrangement that the scientists warn is problematic both for fairness and for sustaining the conservation gains. While the locals benefit from healthier fish populations, it’s dwarfed by the scale of the protection they provide. Under the current arrangement it costs 95 cents for each hectare protected – and that doesn’t count the upland forests. By contrast, paying two people to guard a lake at the typical daily wage for the region would cost $5.30 per hectare each year. Using agents working for the federal environmental protection agency would cost double that – $9.60 per acre.

The findings show “the glaring lack of social justice behind this strategy” given the demands it places on local communities, the scientists write.

“Recognizing the vital role local people play in protecting the Amazon rainforest and supporting local communities are essential for long-term conservation and a crucial matter of social justice,” says Ana Carla Rodrigues of Brazil’s Universidade Federal de Alagoas, who led the research.

Carla Rodrigues, et. al. “Community-based management expands ecosystem protection footprint in Amazonian forests.” Nature Sustainability. Sept. 19, 2025.