How to protect nature and climate in legislation during a housing crisis.

In Australia

Environmentalists worry as Labor seeks consensus on new federal nature laws

Environment minister Murray Watt is restarting the process after the government shelved earlier proposed reforms

Dan Jervis-Bardy and Lisa Cox in The Guardian Australia Sat 14 Jun 2025

A select group of environment and industry leaders will be brought together in a fresh attempt to build consensus on a long-awaited rewrite of federal nature laws, Guardian Australia can reveal.

The environment minister, Murray Watt, will soon detail the next phase of consultation as he presses ahead with an ambition to enact sweeping changes to the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act (EPBC) in the next 18 months.

After the first-term Albanese government shelved proposed reforms amid lobbying from miners and the Western Australian government, Watt has restarted the process.

the first-term Albanese government shelved proposed reforms amid lobbying from miners and the Western Australian government

The past failures, combined with the approval of major fossil fuel projects and the rushed passage of laws to protect Tasmania’s salmon industry, have environmentalists worried about Labor’s second term.

But they also believe Labor’s resounding election victory gives it scope to act “quickly and boldly” to deliver serious reform.

“Australians are tired of the bush being bulldozed and burnt and elected a government that will act on nature and on climate,” the Wilderness Society’s national campaigns director, Amelia Young, said.

A new standard

Almost five years have passed since Graeme Samuel handed his review of the EPBC Act to the then environment minister Sussan Ley, exposing how the systemic failures of successive governments had left Australia’s unique species in unsustainable decline.

The centrepiece of Samuel’s 38 recommendations was a set of national environmental standards turning Australia’s laws from a process-focused system to one focused on outcomes.

Standards that deliver outcomes for the environment and reverse wildlife decline are one of the big demands of the environment movement in this term.

“You’d want to see national environmental standards stipulating places that development should be off limits, such as critical habitat or essential breeding populations,” said James Trezise, the director of the scientist-led Biodiversity Council.

A suite of national environmental standards was supposed to form the third stage of Labor’s Nature Positive Plan, which never saw the light of day as the government prioritised its ultimately doomed environment protection agency (EPA).

The decision of Watt’s predecessor, Tanya Plibersek, to split the reform into stages – starting with the federal EPA – was widely criticised as delaying the urgent task of fixing the EPBC Act.

Senior Labor sources confirmed Watt was leaning toward a different route, pursuing an EPA and amendments to the EPBC Act in one package to avoid dragging out the process.

Environmental organisations also want an end to the “climate blindness” of Australia’s environmental laws, an end to loopholes such as the effective exemption granted to logging under regional forest agreements, and a clearer focus on what’s needed for the recovery of threatened species.

Brendan Sydes, the Australian Conservation Foundation’s national biodiversity policy adviser, said any reform package needed to address the “highly discretionary” nature of the existing laws.

“Because otherwise we just continue to have a situation where people can continue to bring forward proposals that destroy threatened species habitat,” he said.

A watchdog with teeth

The biggest point of tension between industry and environmental groups might be something the Samuel review never even recommended.

Whereas Samuel advocated for a commissioner to monitor and audit the processes governments used to make environmental decisions, Labor proposed an entirely new agency that would both enforce nature laws and assess projects.

Anthony Albanese offered to strip the agency of decision-making powers in a failed attempt to win the Coalition’s support in the previous term.

The design of the EPA 2.0 is up in the air – and will be fiercely contested.

Environment groups including the Australian Conservation Foundation maintain the watchdog must have compliance and decision-making powers and be governed by an independent board.

“We need an independent regulator with responsibility for decision-making on assessments and approvals, rather than just a compliance and enforcement EPA,” Sydes said.

Industry groups that represent major mining companies are staunchly opposed to such a model, instead favouring Samuel’s approach.

The Chamber of Minerals and Energy of Western Australia – whose members include BHP and Rio Tinto – argues a new federal decision-maker would add another layer of “bureaucratic duplication” to an already lengthy and complex environmental approval process.

Bran Black, the chief executive of the Business Council of Australia, said the existing laws were not working for the environment or industry.

“Australia urgently needs faster approvals for projects, so we can deliver more renewable energy projects, build more homes and access more critical minerals,” Black said.

A balancing act

Even if he can broker agreement between environment and industry, Watt would still need to negotiate the laws through federal parliament.

Labor will have two clear, distinct pathways to get legislation passed in the new Senate: deal with the Coalition or deal with the Greens.

Both sides are under new leadership, with the ascension of Ley – who commissioned the Samuel review – offering Labor hope that the Coalition will adopt a more conciliatory approach.

The opposition will face pressure to work with Labor from industry groups including the Minerals Council of Australia, which is desperate to sideline the Greens.

The new shadow environment minister, Angie Bell, said the Coalition would “carefully consider” any proposed reforms.

“We all want to see our outdated environmental laws fixed, but the approach of the Labor government in the previous parliament didn’t get the balance right, and did not have industry or environmental groups on board,” Bell said.

“Our environmental laws must find a balance that protects the environment while not wrapping industries in unnecessary green tape.”

The Greens environment spokesperson, Sarah Hanson-Young, said the overhaul would only be “credible” if it included an end to native logging and a “climate trigger” – the term used to describe a mechanism to account for a project’s greenhouse gas emissions in environmental assessments.

The Greens dropped the climate trigger as a demand during negotiations with Plibersek, which almost ended in a deal before an intervention from Albanese killed it off.

Watt’s provisional approval of a 40-year extension of Woodside’s North West Shelf gas plant has renewed the case for some form of trigger mechanism.

Watt is also facing internal pressure to include climate “considerations” in the nature laws after the Labor MP Jerome Laxale publicly backed the principle.

Then there are grassroots Labor members, who have picked themselves up after the devastation of the collapse of the EPA proposal.

Felicity Wade, the national co-convener of the Labor Environment Action Network, was confident Watt could “walk the line”, listening to business without losing sight of why the legislation existed.

Wade said corporate Australia needed to “leave its bludgeons at the door” as the process started afresh.

Ending habitat loss was the “bottom line outcome”

Ending habitat loss was the “bottom line outcome”, she said, meaning that native forest logging and agricultural land clearing must be addressed in some form.

In the UK

From The Guardian newsletter by Sandra Laville

If you walk down an unpromising, overgrown pathway which winds behind a school on Portsea Island in Portsmouth, you are rewarded a few minutes later when the landscape bursts open to reveal the vast estuary stretching across to Porchester Castle. When you stand still for a moment, you see the coastal meadows and mudflats below are teeming with birds, where human activity is minimal. Known as Tipner West, this stretch of estuarine landscape is considered such an important habitat for wildlife that it has been given the strongest national and international designations. When Labour came to power with its much-vaunted and welcome promise to oversee the building of 1.5m homes and 150 major infrastructure projects, most people concerned with wildlife protection were hopeful that the push for growth would be crafted to take a bow to nature, particularly in the most sensitive spaces on our island such as Tipner West, which are often the last hope for threatened wildlife. That hope is now under threat.

The planning and infrastructure bill was laid before parliament in March by the housing secretary, Angela Rayner. By that time, the rhetoric from the most senior figures in government – the prime minister, the chancellor and Rayner herself – had taken on a tone that seemed to be out of the Trumpian playbook. The target of their ire was nature, in all its forms, and those who decided to try to protect it, who were called “blockers”. The talk was about cutting red tape to “focus on getting things built, and stop worrying about the bats and the newts”.

Ecologists and environmentalists tend to be gentle people; most try to work within the system rather than demonstrating loudly from outside it. When I started looking at the bill, there was still a feeling among environmental NGOs that the government would listen, and protect nature in its legislation.

The most contested part of the bill is the creation of a system that allows developers to in effect pay for nature credits, which can be used to create habitats away from their development site as compensation for damage from a development.

removes the need for developers to do their own environmental assessment

Crucially, this removes the need for developers to do their own environmental assessment on a site to avoid damage and minimise any damage they cause, and then restore and offset the damage done – this is known as the mitigation hierarchy, and is a key part of environmental law.

Instead, they will pay into a nature restoration fund, managed by Natural England, which will allow them to start work immediately, and their money will be used at a later date – there is no rigid timescale – to create habitats elsewhere in environmental development plans created and run by Natural England. Once they have paid into the fund, the bill states, developers can “disregard” the impact of destroying a protected feature.

As the days and weeks have gone on, these same gentle individuals working in ecology and the environment have become increasingly frustrated, angry and disheartened by Labour’s approach.

It is not just an emotional response. A considered line-by-line examination of the legislation in three separate legal opinions has led the likes of the RSPB – not known for hyperbole or direct action – to call the bill a “licence to kill nature”.

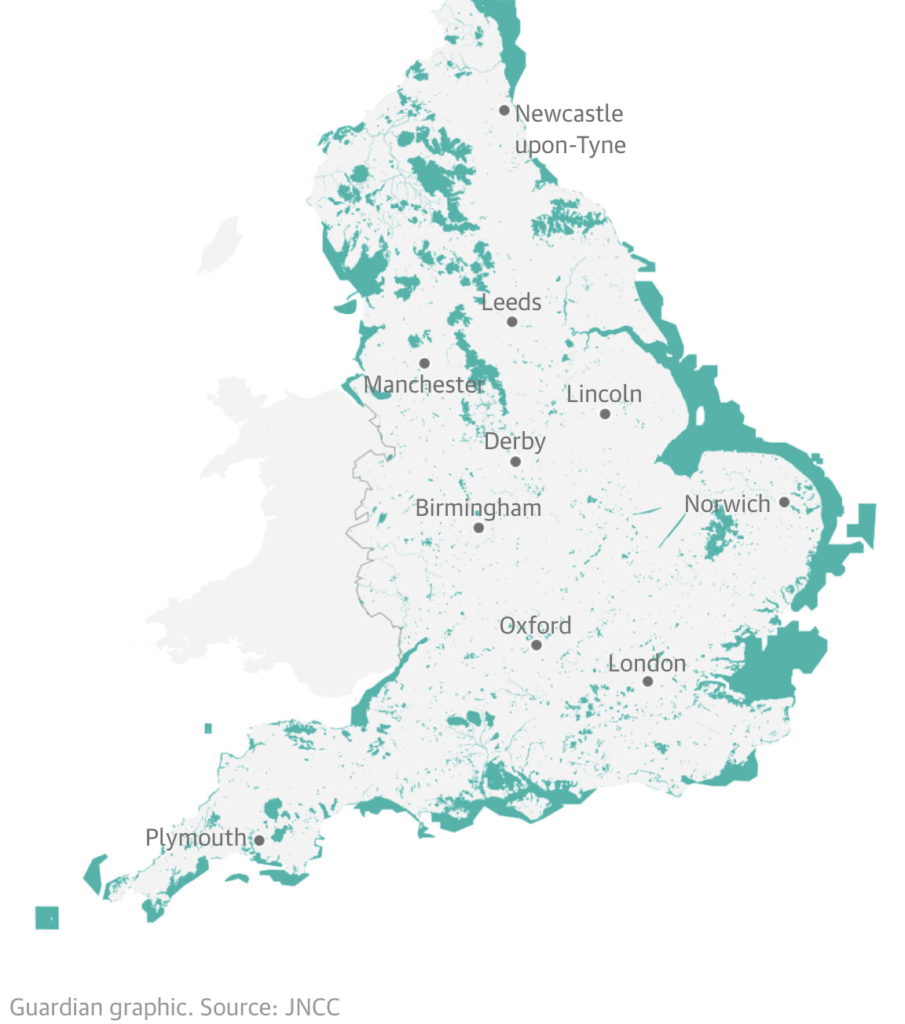

To illustrate what the bill means for the most protected habitats in England, the Guardian has mapped the more than 5,000 ancient woodlands, wetlands, chalk streams and heathlands that have the greatest protection in law because they are irreplaceable wild places.

We examined 10 of these areas that are already, despite their protections, under extreme threat from developers to highlight what legal opinions say is the rolling back of environmental law. This means the most special natural gems in England are more likely to be developed under the bill.

As Alex Goodman KC said in one legal opinion, the legislation withdraws the principal legal safeguard for protected sites. “This amounts to a very significant change,” he said.

the legislation withdraws the principal legal safeguard for protected sites

It’s not just these very special areas that are under threat. Less elevated but no less loved, wildernesses and wetlands – such as local streams, woodland and green spaces that are locally treasured – are all at risk from a weakening of environmental law in the push for growth.

Economically, too, nature has more value than it is ever credited for in current calculations of GDP. As part of our stories, we examined the economics of nature contained in the Dasgupta Review.

The 610-page report to the Treasury in 2021 by the eminent economist Sir Partha Dasgupta was a groundbreaking number-crunching of the value of nature to the economy. It showed that when nature is in decline there is a financial as well as an environmental deficit – the loss of nature will have an impact on the growth so desperately sought by government.

fight to persuade those at the top of government that there is economic value in protecting [nature]

With nature in crisis in the United Kingdom, the fight to persuade those at the top of government that there is economic value in protecting it is set to escalate as the bill returns to parliament this week.

Labour has pledged to deliver 1.5m new homes by the end of the parliament, a target that ministers have admitted will be difficult to meet. Photograph: Flyby Photography/Alamy

This article is more than 3 months old

English and Welsh councils to have greater powers to seize land for affordable housing

This article is more than 3 months old

Exclusive: Compulsory purchase orders will no longer need Whitehall permission under shake-up of planning rules

Eleni Courea Political Correspondent

Mon 10 Mar 2025 11.01 AEDTShare

Councils and mayors will be granted greater powers to seize land to build affordable housing under the Labour government’s shake-up of planning rules this week.

Local authorities in England and Wales will no longer need permission from central government to make compulsory purchase orders (CPOs), in a change that ministers hope will unlock vacant and derelict land.

The change will be made as part of the planning and infrastructure bill, which is expected to be introduced to parliament on Tuesday. It follows the closure last month of a public consultation on the mooted changes to the planning system.

As part of an overhaul of CPO rules, local authorities will no longer need to take into account a property’s “hope value” – an estimate of what it would be worth with planning permission.

a property’s “hope value” – an estimate of what it would be worth with planning permission

Under changes introduced by the Conservatives, councils could ask ministers for permission to buy land without regard to its hope value on a case-by-case basis. Labour’s legislation will introduce a general rule allowing councils to buy land to build homes without paying its hope value.

Councils are being encouraged to make greater use of CPOs to build housing. The government said the changes would mean that homes and large infrastructure projects such as schools and hospitals could be built more quickly and cheaply, helping to regenerate local areas.

Labour pledged to deliver 1.5m new homes by the end of the parliament, a target that ministers have admitted will be difficult to meet. The party has put housing affordability at the heart of its pitch to voters and vowed to get more young people on to the property ladder.

The planning bill will introduce sweeping changes to the planning process, including greater powers for mayors and local authorities, intended to speed up housebuilding and unblock delays. In January, Keir Starmer vowed to end the “challenge culture by taking on the Nimbys” who use repeated legal challenges to block building projects.

Angela Rayner, the deputy prime minister and housing secretary, said on Monday that ministers wanted to “see regeneration happening in every part of this country”, adding: “And to do that we need to make sure public bodies have the tools they need to unlock vacant and derelict sites for public benefit.”

“We’ve been clear that use of these powers should be considered where negotiations to acquire land by agreement are failing and holding back progress. These new powers will support councils and others play their part in delivering 1.5m homes, with the biggest boost to affordable and social housing in a generation, alongside vital infrastructure as part of our Plan for Change.”

Leicester city council used its compulsory purchase powers a decade ago for the regeneration of the city’s waterside area, which has involved the construction of 1,000 houses and development of 9,000 sq metres (96,875 sq ft) of office space.

The area, which had been in decline since the closure of local industries in the 1980s, was comprehensively redeveloped after the council used CPOs to buy the 7-hectare (17-acre) site and demolish derelict buildings.