National Climate Disaster Fund: a solution not just for the uninsurable

Betting the house: Australia’s uninsured and underinsured households and the climate crisis

27 MAY 2025

Home insurance Climate change Extreme weather events Climate risk Households Australia

RESOURCES

| Betting the house: Australia’s uninsured and underinsured households and the climate crisis | 493.12 KB |

DESCRIPTION

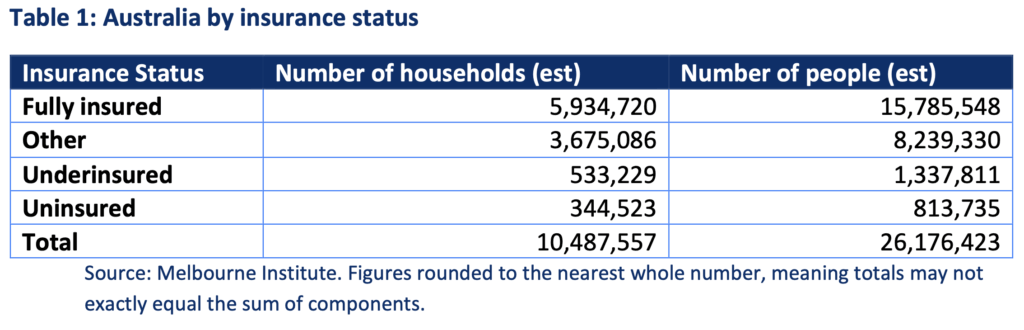

This paper analyses rates of underinsurance and uninsurance in Australia at a time when the severity and frequency of climate disasters is increasing. It finds that in 2023, about one in 30 Australian households did not have home building insurance, and one in 20 Australian households was underinsured. Banks in Australia hold over $100 billion in mortgages on inadequately insured properties, posing significant risks to the broader Australian economy.

As climate disasters cause an increasing amount of damage, insurance prices are pushed upwards. This paper argues the Australian Government is making things worse through not taking stronger action to reduce climate impacts by addressing fossil fuel emissions.

By taxing fossil fuel companies to pay for the costs of the climate crisis, the Commonwealth could create a National Climate Disaster Fund. This fund could be used to help pay for the costs of natural disaster response and recovery, and invested in mitigating the extent of climate change and preparing for its already locked-in impacts. This would help keep Australians safe and help bring down insurance prices.

Key findings

- 344,523 Australian households are not insured.

- 533,229 Australian households are underinsured.

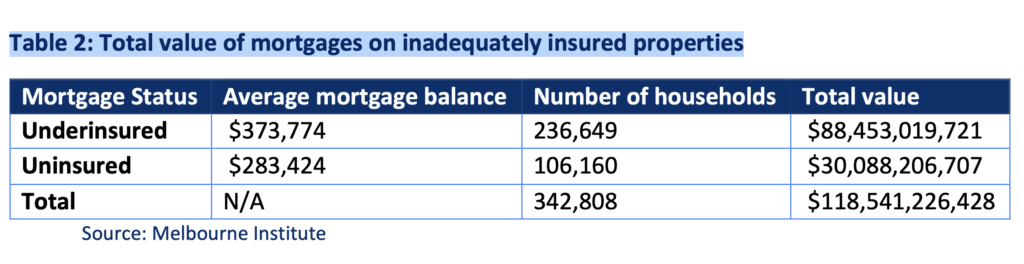

- Mortgages on underinsured homes are worth a total of $88.5 billion, while those on uninsured homes are worth $30.1 billion.

- In 2022, nearly one in 20 Australians – the highest proportion on record – experienced the destruction of or damage to their home due to weather-related disasters.

Summary

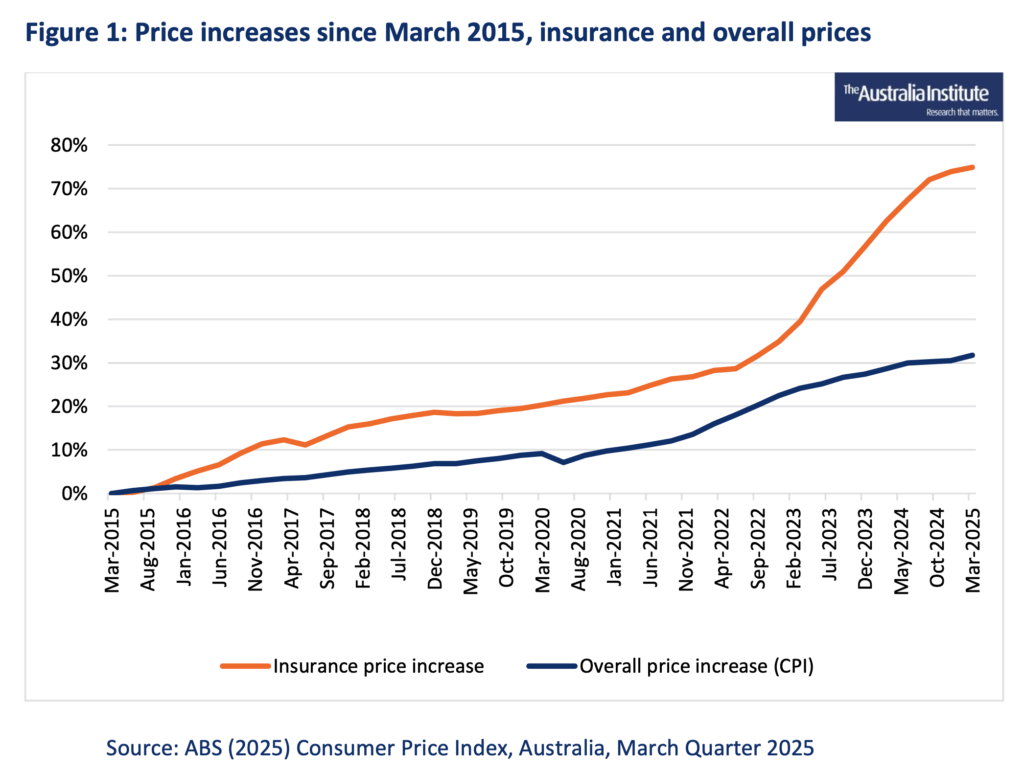

Climate change is already here and getting worse, causing increasingly damaging disasters, and pushing insurance prices higher.

This report draws on data from the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey to analyse rates of under and uninsurance in Australia at a time when the severity and frequency of climate disasters is increasing.

It finds that, in 2023, about one in 30 Australian households did not have home building insurance, and one in 20 Australian households was underinsured. This is over 800,000 households and over 2 million people. Over 300,000 Australian households with mortgages were either uninsured or underinsured. As full building insurance is usually a contractual condition for mortgages, these households risk substantial losses if disaster hits or if the bank finds that they have breached their mortgage conditions.

The analysis in this paper suggests that banks in Australia hold over $100 billion in mortgages on inadequately insured properties, and likely much more. As mortgage lending dominates the Australian financial system, with two-thirds of banks’ total domestic lending dedicated to housing loans, this poses significant risks to the broader Australian economy.

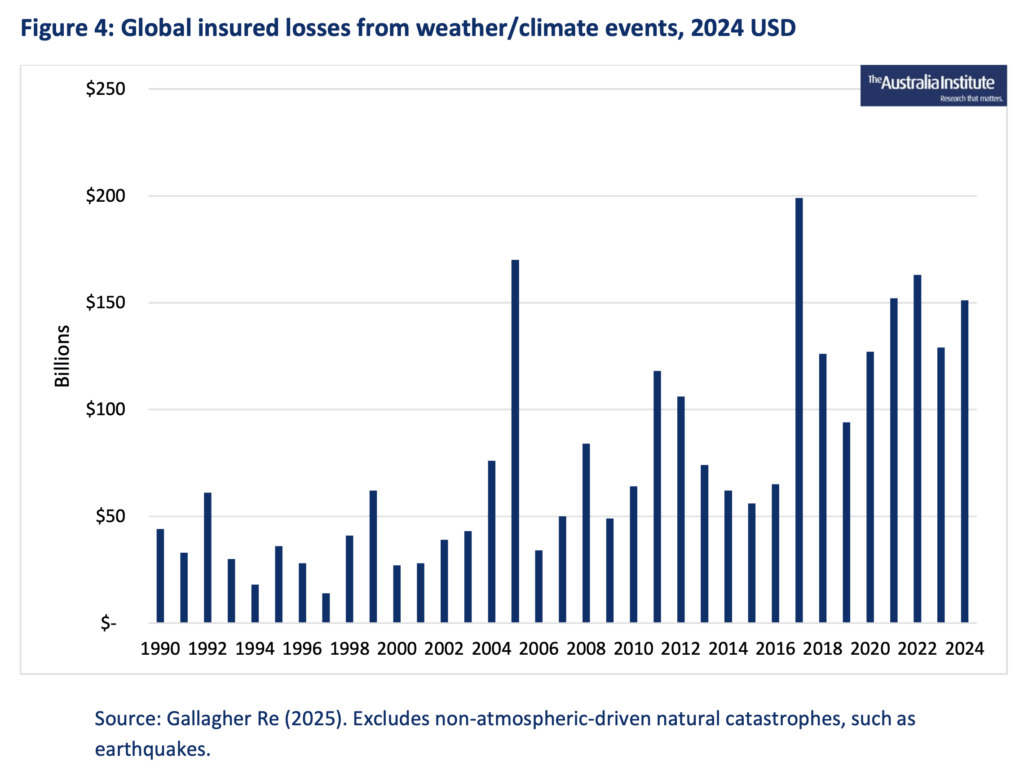

Climate disasters are impacting an increasing number of people and causing an increasing amount of damage. This is pushing insurance prices upwards. In 2022, nearly one in 20 Australians saw their home damaged or destroyed because of a weather-related disaster. In Australia, every year since 2013 has seen more insured losses than the total combined losses from 2000 to 2004. Globally, even accounting for inflation, insured losses for the first five years of the 2020s were USD$722 billion globally, almost double the losses for the entire 1990s (USD$367 billion).

Unfortunately, the Australian Government is pouring fuel on the fire. Through the huge subsidies given to fossil fuels, and by allowing the production of fossil fuels to expand, current policies are enabling further climate pollution. By instead taxing fossil fuel companies to pay for the costs of the climate crisis, the Commonwealth could create a National Climate Disaster Fund. This fund could be used to help pay for the costs of natural disaster response and recovery, and invested in mitigating the extent of climate change and preparing for its already locked-in impacts. This would help keep Australians safe and help bring down insurance prices.

Introduction

Floods, fires, and other climate disasters are becoming more frequent and more severe. When the water recedes, or the ashes cool, the difference between being able to rebuild the family home and financial ruin can come down to whether or not a homeowner has enough insurance.

Analysis by the Climate Council shows that over 650,000 Australian properties (about one in 23) are already at ‘high risk’ of disasters such as flooding, bushfire, coastal inundation, or tropical cyclone. By 2050, as the risk of climate disaster increases, more than 100,000 more

1 homeowners, especially if they do not have adequate insurance.

properties will be added to the high-risk category.

This report draws on data from the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia

(HILDA) Survey to analyse rates of underinsurance and uninsurance in Australia.

on questions first asked in “wave 23” of the HILDA survey, which were released in December 2024. As the HILDA survey is unique in its scale, breadth, and longitudinal design, these results provide a valuable opportunity to analyse if and how households are insuring themselves in the context of rising insurance costs and increasingly damaging climate disasters. Using this data, we estimate that the total value of mortgages on inadequately insured properties is approximately $119 billion. However, it is important to note that other studies indicate that the scale of underinsurance and uninsurance in Australia is substantially higher than estimated by the HILDA survey.

Insurance is not primarily to protect homeowners against potential damage, but to ensure the financial safety of a bank’s assets. Given that the $119 billion of inadequately insured mortgages accounts for about 5.4% of all mortgages, inadequate insurance could pose a threat to the stability of the overall Australian financial system.

All over the world, insurance costs are soaring because of climate change. Disasters in other parts of the world impact insurance payers in Australia. This is because Australian insurance companies take out their own insurance from the global ‘reinsurance’ market. In response to rising costs and risks across the world, reinsurers raise the price of reinsurance, which flows through to Australian insurance prices. By changing the policies that encourage the production and consumption of fossil fuels, the Australian Government could help lower the risk of climate disaster both to homeowners and to the Australian financial system.

To this end, the Australia Institute recommends the establishment of a National Climate Disaster Fund to help pay for the costs of natural disaster response and recovery for Australian households, businesses, and taxpayers, and investment in mitigating the extent of climate change and preparing for its already locked-in impacts. This would be funded through a ‘climate damage compensation levy’ of $1 per tonne of carbon dioxide for all coal, gas and oil produced in Australia.

1 Climate Council (2025) At Our Front Door: Escalating Climate Risks for Aussie Homes, https://www.climatecouncil.org.au/resources/escalating-climate-risks-for-aussies-homes/

2 Melbourne Institute (n.d.) HILDA Survey, https://melbourneinstitute.unimelb.edu.au/hilda

The scale of the problem

WHAT IS UNINSURANCE AND UNDERINSURANCE?

Using the HILDA survey, Australian households can be roughly divided into four ‘insurance categories’:

- Fully insured – owner-occupiers with building insurance that covers a complete rebuild of the home.

- Underinsured – owner-occupiers with building insurance that only partially covers a complete rebuild of the home.

- Uninsured – owner-occupiers without building insurance.

- Other – non-owner-occupiers, such as renters. When referring to both underinsured and uninsured categories, this paper uses the term ‘inadequately insured’. It is standard practice for banks to require mortgagors to have full building insurance. For instance, the Commonwealth Bank of Australia requires that mortgagors: must at all times maintain Building Insurance over all Security Property, other than vacant land, for an amount at least equal to the full replacement cost of any building and other improvements on the Security Property. … [and] The Building Insurance must cover fire, storm, flood, hail, cyclone and other building risks as we may reasonably specify in accordance with our usual credit standards. 3

- If the mortgagor fails to meet this condition, they will either be in default, or the bank may 4 adjust their interest rate. Both ANZ and NAB have similar terms and conditions on their standard home loan terms and conditions.5

- 3 Commonwealth Bank (2024) Consumer Mortgage Lending Products Terms and Conditions, https://www.commbank.com.au/content/dam/commbank/personal/apply-online/download-printed- forms/utc-home-loan.pdf

- 4 Commonwealth Bank (2024) Consumer Mortgage Lending Products Terms and Conditions

- 5 ANZ Bank (2024) Consumer Lending: Terms and Conditions, https://www.anz.com.au/content/dam/anzcomau/documents/pdf/consumer-lending-tc.pdf; National Australia Bank (n.d.) Home Loan General Terms, https://www.nab.com.au/content/dam/nabrwd/documents/terms-and-conditions/loans/home-loan- general-terms.pdf

HOW MANY HOUSEHOLDS ARE INADEQUATELY INSURED?

According to the latest results of the Melbourne Institute’s Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey, in 2023, one in 20 Australian households (5.1%) was underinsured, and about one in 30 (3.3%) was uninsured. This is over 800,000 households and over 2 million people (Table 1).

The cost of insurance is a leading reason for inadequate coverage. About half (46%) of underinsured households did not fully insure their building because insurance was seen as either too expensive, poor value for money, or both. Similarly, about half (51%) of uninsured households did not have building insurance because it was seen as either too expensive,

MORTGAGING WITHOUT INSURANCE

Climate change aggravates this crisis

The price of insurance essentially derives from:

- the likelihood of damage – higher risks mean higher prices;

- the cost of rebuilding – more extensive damage or more expensive rebuilding processes mean higher prices;

- administrative costs; and

- profits made by the insurance company. Climate change is exposing more people to weather-related disasters such as floods, bushfires, and cyclones. According to the HILDA survey, 2022 saw nearly one in 20 (4.4%) Australians — the highest proportion on record — experience the destruction of or damage

to their home due to weather-related disasters (Figure 2). This is the same year that floods swept Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria, Tasmania, and South Australia. The previous record, about one in 37 people (2.7%), was set in 2011, which saw flooding in Brisbane, Cyclone Yasi hit north Queensland, and severe storms (including the Christmas Day Hailstorm) in Melbourne.

RISING INSURANCE COSTS ARE A GLOBAL ISSUE

CLIMATE PRESSURES WILL CONTINUE TO INTENSIFY

Analysis by the Climate Council shows that over 650,000 Australian properties (about one in 23) are already at ‘high risk’ of one or more hazards such as flooding, bushfires, coastal inundation, and tropical cyclones.

A further 1.55 million properties (or 1 in 10) are at moderate risk. 24 The most at-risk federal electorates are identified as: 25

- Nicholls (Vic)

- Richmond (NSW)

- Maranoa (QLD)

- Moncrieff (QLD)

- Wright (QLD)

- Brisbane (QLD)

- Griffith (QLD)

- Indi (Vic)

- Page (NSW)

- Hindmarsh (SA)26

24 Climate Council (2025) At Our Front Door: Escalating Climate Risks for Aussie Homes

25 Climate Council (2025) At Our Front Door: Escalating Climate Risks for Aussie Homes

26 Climate Council (2025) At Our Front Door: Escalating Climate Risks for Aussie Homes

High-risk properties are at risk of becoming uninsurable, as insurance companies may be unwilling to provide cover, or only provide cover at prohibitively high prices. 27 Climate change has already driven more properties into the high-risk category and, by 2050, more than 100,000 properties will be added to the high-risk category as climate risks intensify. The rate at which this happens will depend on how quickly the planet manages 28 to decarbonise.

CHOOSING A DIFFERENT PATH

By reducing emissions and adapting to already locked-in climate impacts, Australia has the opportunity to lower climate risks and make insurance cheaper. Halting the approval and expansion of fossil fuel projects, and eliminating fossil fuel subsidies, would be a start. Thegovernment could also move to raise money from the fossil fuel industry, which is responsible for the climate crisis, by increasing royalties or the PRRT, or even implementing new taxes or levies. The Australia Institute has long argued for a National Climate Disaster Fund, which would help pay for the costs of natural disaster response and recovery for Australian households, businesses, and taxpayers. This would be funded through a ‘climate damage compensation levy’ of $1 per tonne of carbon dioxide for all coal, gas and oil produced in Australia. Alternatively, Professors Rod Sims and Ross Garnaut of the Superpower Institute have proposed a ‘carbon solutions levy’ on Australian fossil fuel extraction sites and imports, which could raise up to $100 billion in it’s first year. Other options could include a polluter-pays tax, windfall profits taxes on oil and gas companies or levies on fossil fuel exports.

Funds raised by these taxes and levies could then be invested in mitigation and adaptation strategies that will be vital to limiting and managing climate risks. Significant investments, including in the industrial, residential, transportation and agricultural sectors, are needed for Australia to bring down emissions and to transition off fossil fuels. Meanwhile, climate adaptation strategies will be vital to managing the risks and impacts of the climate change that is already locked in. This will necessitate measures such as investments in strengthening public infrastructure, social services, and public health. In worst-case scenarios, it may become necessary to pay for whole communities to relocate.

Detailed HILDA results