Survival of the greenest: Older companies are surprisingly more sustainable than younger ones

A new study upends assumptions about old organizations as incapable of change—and younger ones having a “greenness” native to their era of environmental concern.

June 10, 2025

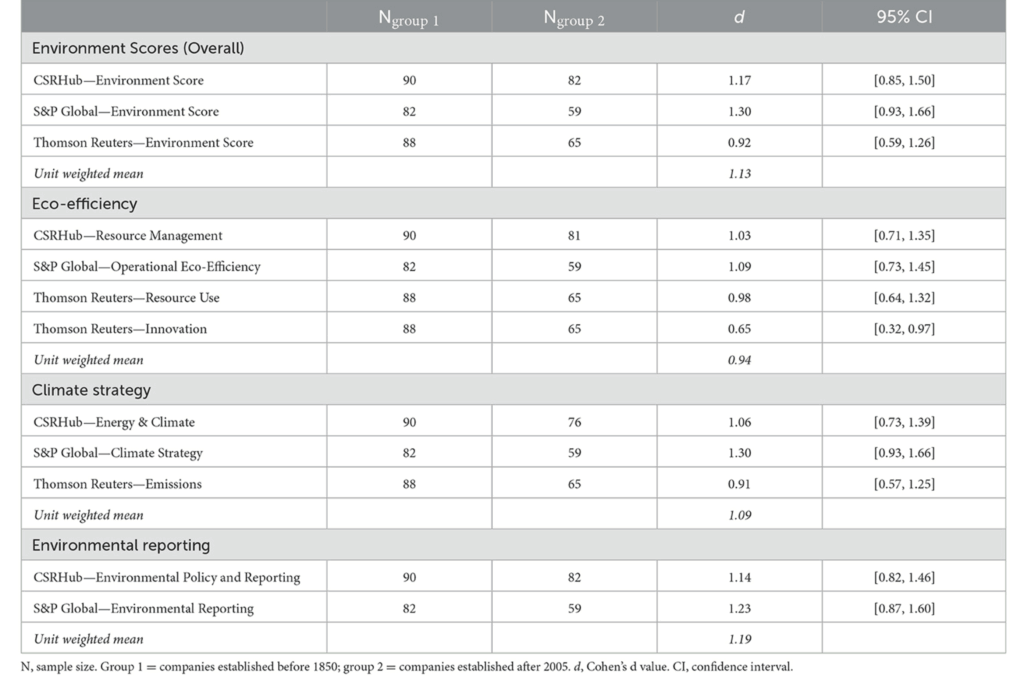

Table 5. Mean differences in environmental sustainability performance between oldest and youngest companies. What it measures: Cohen’s d quantifies how much the means of two groups differ, expressed in terms of how many standard deviations apart they are. How it’s calculated: The formula for Cohen’s d is: d = (mean1 – mean2) / standard deviation. The choice of standard deviation depends on the research design (pooled, control group, or pretest). Interpreting Cohen’s d: A d of 0.2 is considered a “small” effect, 0.5 a “medium” effect, and 0.8 a “large” effect. These values are guidelines and can be interpreted differently depending on the context. When to use it: Cohen’s d is commonly used to accompany t-tests, ANOVA results, and in meta-analyses. It’s also helpful in estimating sample sizes for future studies. Limitations: Cohen’s d has some limitations, including the assumption of equal variances (homoskedasticity). It’s also important to consider the practical significance of the effect size, even if it’s statistically significant. In essence, Cohen’s d helps researchers understand the magnitude of the difference between two groups, beyond just knowing if the difference is statistically significant.

Older companies are more environmentally sustainable than younger ones, according to a new analysis. The findings upend popular assumptions of old organizations as hidebound and incapable of change, and younger ones as having a “greenness” native to their era of environmental concern.

“Lasting organizations have learned to adapt, again and again, across changing environments, including those in the natural world. Over decades, they have built deep-rooted habits, systems, and values that support adaptive practices,” research team members University of Pennsylvania student Daria M. Haner, City University of New York professor Stephan Dilchert, and University of Minnesota professor Deniz S. Ones wrote in a statement to Anthropocene. “Organizational age can be an asset for the planet.”

The researchers assembled a list of top tech, finance, and manufacturing companies in the United States, Europe, the Middle East and North Africa, and Asia. They analyzed the companies’ establishment and incorporation dates in relation to their environmental, social, and governance (ESG) ratings from multiple independent organizations including CSRHub, S&P Global, and Thomson Reuters.

Overall and in every region, older companies have better environmental metrics than younger companies, the researchers report in the journal Frontiers in Organizational Psychology.

“This edge is not just about size or wealth,” the researchers told Anthropocene. “Even after accounting for both, organizational longevity still relates to environmental sustainability performance.” (This pattern and others are somewhat less evident in Europe, probably because of missing information about companies’ incorporation dates.)

When trees face drought and climate change, old age trumps youth

The analysis suggests that surviving as a business requires a knack for adapting to changing markets, social norms, and environmental conditions over time. Older companies have developed the structures, discipline, and resources required to carry out long-term goals.

surviving as a business requires a knack for adapting

The sustainability advantage is particularly pronounced when the oldest companies—90 firms established before 1850—are compared with the youngest ones—82 companies established after 2005. The oldest companies are especially strong when it comes to transparency and environmental reporting, which may reflect that these firms are experienced at responding to public scrutiny.

oldest companies are especially strong when it comes to transparency and environmental reporting

The advantage of age is least pronounced—though still present—in the realm of innovation. This finding “[hints] at a limit: experience strengthens structure, but may not fuel cutting-edge change,” the researchers said in their statement.

The results suggest that businesses have different sustainability-related strengths and weaknesses at different points in their lifecycle. Policymakers should reward the sustainability chops of older companies and encourage them to adopt cutting edge environmental innovations, while designing policies to help younger businesses develop sustainability strategies and the resources to carry them out, the researchers argue.

Around the world, corporate life expectancies are declining and corporate environmental footprints are expanding. But the new results suggest that a good ESG score signals a good investment opportunity, a company that is likely to be robust and adaptable over the long term. Sustainability and longevity become a “virtuous cycle,” with businesses that pay attention to sustainability better able to stand the test of time.

a good ESG score signals a good investment opportunity

In the future, the researchers aim to delve deeper into how longevity contributes to sustainability, exploring possible mechanisms related to HR departments, corporate boards, and aspects of organizational culture. They also want to understand how different laws, history, and culture contribute to the longevity-sustainability link across countries.

Source: Haner D.M. et al. “Survival of the greenest: environmental sustainability and longevity of organizations.” Frontiers in Organizational Psychology 2025.

References

Adams, C. A. (2004). The ethical, social and environmental reporting-performance portrayal gap. Account. Audit. Account. J. 17, 731–757. doi: 10.1108/09513570410567791

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Ahmed, F., Hu, W., Arslan, A., and Huang, H. (2024). Ambidexterity of HR practices in fortune 500 companies and employee innovation performance: mediating role of inclusive leadership. J. Organizat. Change Managem. 37, 237–254. doi: 10.1108/JOCM-05-2022-0139

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Amel, E., Manning, C., Scott, B., and Koger, S. (2017). Beyond the roots of human inaction: Fostering collective effort toward ecosystem conservation. Science 356, 275–279. doi: 10.1126/science.aal1931

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Asian Development Bank (2017). ASEAN Corporate Governance Scorecard Country Reports and Assessments 2015: Joint Initiative of the ASEAN Capital Markets Forum and the Asian Development Bank. Washington D.C.: Asian Development Bank.

Banks, G. C., Ross, R., Toth, A. A., Tonidandel, S., Goloujeh, A. M., Dou, W., et al. (2023). The triangulation of ethical leader signals using qualitative, experimental, and data science methods. Leadersh. Q. 34, 101658. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2022.101658

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Bleady, A., Hasaballah, A. H., and Ibrahim, S. (2018). Dynamic capabilities theory: pinning down a shifting concept. Acad. Account. Financ. Stud. J.2018:22.

Brown, M. E., and Trevino, L. K. (2006). Socialized charismatic leadership, values congruence, and deviance in work groups. J. Appl. Psychol. 91:954. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.91.4.954

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Centobelli, P., Cerchione, R., Chiaroni, D., Del Vecchio, P., and Urbinati, A. (2020). Designing business models in circular economy: a systematic literature review and research agenda. Busin. Strat. Environm. 29, 1734–1749. doi: 10.1002/bse.2466

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Chatterji, A., and Levine, D. (2006). Breaking down the wall of codes: Evaluating non-financial performance measurement. Calif. Manage. Rev. 48, 29–51. doi: 10.2307/41166337

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Chatterji, A. K., Durand, R., Levine, D. I., and Touboul, S. (2016). Do ratings of firms converge? Implications for managers, investors and strategy researchers. Strat. Managem. J. 37, 1597–1614. doi: 10.1002/smj.2407

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Chaudhary, R. (2020). Green human resource management and employee green behavior: An empirical analysis. Corp. Soc. Respons. Environm. Managem. 27, 630–641. doi: 10.1002/csr.1827

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Chen, X., Wu, X., and Wang, X. (2023). Organizational Ecology Theory: Review Past for Directing the Future Development.

Christmann, P. (2004). Multinational companies and the natural environment: determinants of global environmental policy. Acad. Managem. J. 47, 747–760. doi: 10.2307/20159616

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Correggi, C., Di Toma, P., and Ghinoi, S. (2024). Rethinking dynamic capabilities in light of sustainability: a bibliometric analysis. Busin. Strat. Environm. 33, 7990–8016. doi: 10.1002/bse.3901

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Daddi, T., Testa, F., Frey, M., and Iraldo, F. (2016). Exploring the link between institutional pressures and environmental management systems effectiveness: an empirical study. J. Environ. Manage. 183, 647–656. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2016.09.025

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

de Almeida Barbosa Franco, J., Franco Junior, A., Battistelle, R. A. G., and Bezerra, B. S. (2024). Dynamic capabilities: unveiling key resources for environmental sustainability and economic sustainability, and corporate social responsibility towards sustainable development goals. Resources 13:22. doi: 10.3390/resources13020022

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Delmas, M., and Blass, V. D. (2010). Measuring corporate environmental performance: The trade-offs of sustainability ratings. Busin. Strat. Environm.19, 245–260. doi: 10.1002/bse.676

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Díaz, S., Settele, J., Brondízio, E. S., Ngo, H. T., Agard, J., Arneth, A., et al. (2019). Pervasive human-driven decline of life on Earth points to the need for transformative change. Science 366:eaax3100. doi: 10.1126/science.aax3100

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Eitrem, A., Meidell, A., and Modell, S. (2024). The use of institutional theory in social and environmental accounting research: a critical review. Account. Busin. Res. 54, 775–810. doi: 10.1080/00014788.2024.2328934

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Elkington, J. (1998). Cannibals With Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business. Gabriola Island, BC: New Society Publishers.

Funder, D. C., and Ozer, D. J. (2019). Evaluating effect size in psychological research: Sense and nonsense. Adv. Methods Pract. Psychol. Sci. 2, 156–168. doi: 10.1177/2515245919847202

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Graham, L. M. (2008). Reparations, self-determination, and the seventh generation. Harvard Human Rights J. 21, 47–104.

Grashuis, J. (2018). An exploratory study of cooperative survival: Strategic adaptation to external developments. Sustainability 10:3. doi: 10.3390/su10030652

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Hannan, M. T., and Freeman, J. (1977). The population ecology of organizations. Am. J. Sociol. 82, 929–964. doi: 10.1086/226424

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Hillman, A. J., Cannella, A. A., and Paetzold, R. L. (2000). The resource dependence role of corporate directors: Strategic adaptation of board composition in response to environmental change. J. Managem. Stud. 37, 235–256. doi: 10.1111/1467-6486.00179

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Hillman, A. J., Withers, M. C., and Collins, B. J. (2009). Resource Dependence Theory: A review. J. Manage. 35, 1404–1427. doi: 10.1177/0149206309343469

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

International Organization for Standardization. (2021). ISO 14031:2021 Environmental management–Environmental performance evaluation—Guidelines. Geneva: ISO. Available online at: https://www.iso.org/standard/81453.html

Kang, M. Y. (2022). What makes companies to survive over a century? The case of Dongwha Pharmaceutical in the Republic of Korea. Sustainability 14:2. doi: 10.3390/su14020946

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Katz, I. M., Rauvola, R. S., Rudolph, C. W., and Zacher, H. (2022). Employee green behavior: a meta-analysis. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environm. Managem.29, 1146–1157. doi: 10.1002/csr.2260

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Kaufman, G., and Petts, R. J. (2022). Gendered parental leave policies among Fortune 500 companies. Community Work Fam. 25, 603–623. doi: 10.1080/13668803.2020.1804324

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Kesner, I. F., Victor, B., and Lamont, B. T. (1986). Board composition and the commission of illegal acts: an investigation of Fortune 500 companies. Acad. Managem. J. 29, 789–799. doi: 10.2307/255945

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Kleindorfer, P. R., Singhal, K., and Van Wassenhove, L. N. (2005). Sustainable operations management. Prod. Operat. Managem. 14, 482–492. doi: 10.1111/j.1937-5956.2005.tb00235.x

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Kwee, Z., Van Den Bosch, F. A. J., and Volberda, H. W. (2011). The influence of top management team’s corporate governance orientation on strategic renewal trajectories: a longitudinal analysis of Royal Dutch Shell plc, 1907–2004. J. Managem. Stud. 48, 984–1014. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6486.2010.00961.x

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Lee, D. (2023). Corporate social responsibility and corporate interlocks: Fortune 500 companies’ performance on the Sustainable Development Goals. Int. J. Organiz. Analysis 31, 3653–3667. doi: 10.1108/IJOA-07-2022-3355

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Maxwell, S. L., Cazalis, V., Dudley, N., Hoffmann, M., Rodrigues, A. S. L., Stolton, S., et al. (2020). Area-based conservation in the twenty-first century. Nature 586, 217–227. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2773-z

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Murphy, A., Poncian, J., Hansen, S., and Touryalai, H. (2018). Global 2000—The World’s Largest Public Companies 2018. Available online at: https://www.forbes.com/global2000/ (accessed October 30, 2024).

Napolitano, M. R., Marino, V., and Ojala, J. (2015). In search of an integrated framework of business longevity. Bus. Hist. 57, 955–969. doi: 10.1080/00076791.2014.993613

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Norton, T. A., Parker, S. L., Zacher, H., and Ashkanasy, N. M. (2015). Employee green behavior a theoretical framework, multilevel review, and future research agenda. Organ. Environ. 28, 103–125. doi: 10.1177/1086026615575773

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Ones, D. S., and Dilchert, S. (2012). “Employee green behaviors,” in Managing Human Resources for Environmental Sustainability, eds. S. E. Jackson, D. S. Ones, and S. Dilchert (New York: Jossey-Bass/Wiley), 85–116.

Ones, D. S., and Dilchert, S. (2013). “Measuring, understanding, and influencing employee green behaviors,” in Green Organizations: Driving Change with I-O psychology, eds. A. H. Huffman and S. R. Klein (London: Routledge), 115–148.

Ones, D. S., Wiernik, B. M., Dilchert, S., and Klein, R. M. (2018). “Multiple domains and categories of employee green behaviors: more than conservation,” in Research Handbook on Employee Pro-Environmental Behaviour, eds. V. K. Wells, D. Gregory-Smith, and D. Manika (Worcestershire: Edward Elgar), 13–38.

Orlitzky, M., Schmidt, F. L., and Rynes, S. L. (2003). Corporate social and financial performance: a meta-analysis. Organiz. Stud. 24, 403–441. doi: 10.1177/0170840603024003910

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Paillé, P. (2024). Green human resource practices for individual environmental performance: a meta-review. Can. J. Administ. Sci. 2024:1768. doi: 10.1002/cjas.1768

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Paillé, P., Sanchez-Famoso, V., Valéau, P., Ren, S., and Mejia-Morelos, J. H. (2023). Green HRM through social exchange revisited: when negotiated exchanges shape cooperation. Int. J. Human Resource Managem. 34, 3277–3307. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2022.2117992

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Panza, L., Ville, S., and Merrett, D. (2018). The drivers of firm longevity: age, size, profitability and survivorship of Australian corporations, 1901–1930. Bus. Hist. 60, 157–177. doi: 10.1080/00076791.2017.1293041

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Riviezzo, A., Skippari, M., and Garofano, A. (2015). Who wants to live forever: Exploring 30 years of research on business longevity. Bus. Hist. 57, 970–987. doi: 10.1080/00076791.2014.993617

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Salimath, M. S., and Jones, R. (2011). Population ecology theory: implications for sustainability. Managem. Deci. 49, 874–910. doi: 10.1108/00251741111143595

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Sariatli, F. (2017). Linear economy versus circular economy: A comparative and analyzer study for optimization of economy for sustainability. Visegrad J. Bioecon. Sustain. Dev. 6, 31–34. doi: 10.1515/vjbsd-2017-0005

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Sarta, A., Durand, R., and Vergne, J.-P. (2021). Organizational adaptation. J. Manage. 47, 43–75. doi: 10.1177/0149206320929088

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Scott, W. R. (2005). “Institutional theory: contributing to a theoretical research program,” in Great Minds in Management, eds. K. G. Smith and M. A. Hitt (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 460–484.

Stanek, K. C., and Ones, D. S. (2023). Of Anchors & Sails: Personality-Ability Trait Constellations. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Libraries Press.

Taher, A. (2023). Do corporate values have value? The impact of corporate values on financial performance. Future Busin. J. 9, 76. doi: 10.1186/s43093-023-00254-9

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Tashman, P. (2021). A natural resource dependence perspective of the firm: how and why firms manage natural resource scarcity. Busin. Soc. 60, 1279–1311. doi: 10.1177/0007650319898811

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Teece, D. J., Pisano, G., and Shuen, A. (1997). Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strat. Managem. J. 18, 509–533.

Viguerie, S. P., Calder, N., and Hindo, B. (2021). 2021 Corporate Longevity Forecast. Available online at: https://www.innosight.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Innosight_2021-Corporate-Longevity-Forecast.pdf (accessed February 2, 2025).

Wackernagel, M., Schulz, N. B., Deumling, D., Linares, A. C., Jenkins, M., Kapos, V., et al. (2002). Tracking the ecological overshoot of the human economy. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 99, 9266–9271. doi: 10.1073/pnas.142033699

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Wiernik, B. M., Dilchert, S., and Ones, D. S. (2016). Age and employee green behaviors: a meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 7, 194. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00194

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Wiernik, B. M., Ones, D. S., and Dilchert, S. (2013). Age and environmental sustainability: A meta-analysis. J. Managerial Psychol. 28, 826–856. doi: 10.1108/JMP-07-2013-0221

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

World Commission on Environment and Development (1987). Our Common Future. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Zacher, H., Rudolph, C. W., and Katz, I. M. (2023). Employee green behavior as the core of environmentally sustainable organizations. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 10, 465–494. doi: 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-120920-050421

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Zhou, K. Z., Gao, G. Y., and Zhao, H. (2017). State ownership and firm innovation in China: an integrated view of institutional and efficiency logics. Adm. Sci. Q. 62, 375–404. doi: 10.1177/0001839216674457

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Alternative commentary 2024

Does ESG rating do its job? No, as a matter of fact, has no correlation with the actual environmental performance of corporations.

Is there an efficient way to estimate the corporate environmental performance? Is the ESG indicator able to capture this information? The answer is NO: no correlation has been found with the actual environmental performance of corporations.

Published in Social Sciences, Business & Management, and Economics

Jan 24, 2024

Franco Ruzzenenti, Univerfsity of Groningen

Explore the Research

In his 2020 annual letter to clients, Larry Fink, CEO of BlackRock, prophesized that a “fundamental reshaping of finance” was about to come because “climate risk” was soon to become “investment risk”. In the same letter he vowed to “measurement and transparency”, and listed some “key actions” to be taken, like publishing a temperature alignment metric for our public equity and bond funds, for any markets with sufficiently reliable data 1 . In the years, several other laudable initiatives followed, including GFANZ, a “global coalition of leading financial institutions committed to accelerating the decarbonization of the economy”, accounting for purportedly 40% of global private financial assets. In a press release dated December 2023 GFANZ pledged for an accurate, transparent, and consistently reported emissions data for real economy companies across Scopes, with the awareness that this will help financial institutions assess climate-related risks 2 .

The two-pronged problem of measurement and transparency in the domain of corporate emissions footprint and, more broadly, of environmental performance, is well known to the Gotha of the financial industry, perhaps even more than to the academics, who for the largest part still ignore, disregard or misinterpret the potential role of the corporate world to pursue sustainability.

Most academics believe, perhaps naively, that the main agency of our society still lies in the domain of public politics. But, as brilliantly stated by the Sheldon Wolin in his book Democracy Incorporated, the present reality is marked by a political moment when corporate power finally sheds its identification as a purely economic phenomenon, confined primarily to a domestic domain of “private enterprise”, and evolves into a globalizing co-partnership with the state: a double transmutation, of corporate and state. The former becomes more political, the latter more market oriented.

Put simply, the goal of sustainability and the quest to achieve a transition to a low carbon economy are unattainable without or against global corporations, because there resides the site of major decisions around our World.

It comes without surprise that politicians are often more aware of this crude fact than academics. The EU is trying to engage (and gauge) corporations effectively towards sustainability, and recently there was great focus on the EU Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive. However, as remarked by Ingka’s Simon Henzell-Thomas (IKEA), ESG disclosure rules “are only useful if they … reduce emissions”, as opposed to being “simply seen as a box-ticking exercise”3.

Evidently, there can’t be any accountability or, if you prefer, co-partnership(stewardship?), without measurement and transparency. Thus, the lingering question is, is ESG rating (or the environmental component thereof) transparent, let alone, a good measure of sustainability?

In our study we tested (the environmental score) of one of the most used ESG ratings, that of Sustainalytics and found that it has no correlation with the emissions of global corporations (assessed by size and sector). In the following plot, we compared Sustainalytics ESG ratings and environmental scores for the year 2018 to benchmark deviations of 1104 global corporations for 9 sectors. The Pearson correlation over the whole sample is 0.04, with a p-value of 0.16.

Does the ESG perform better if, instead of corporate emission we consider other environmental impact indicators, such as water withdrawal, waste or energy? Not really. The correlation spans from 0.08 to -0.07.

Experts argue that ESG is a composite and complex indicator that considers, together with emissions/pollution, the broad environmental policy of a corporation. Yet, if complexity reaches the shores of counterfeiting or mystification of the actual environmental impact of an economic activity, what is the use of such metrics for the purpose of guiding (green?) investment, policy scrutiny or public reproach? Does it serve its main purpose of transparency and measurement?

Perhaps, one additional (and little known) reason why ESG ratings fail to assess the environmental performance of corporations is that corporate metabolism is a scaling phenomenon. Assessing the environmental performance of global companies should account for company size in a nonlinear way.

The environmental impact of companies typically scales sub-linearly with size, measured by revenue. This is to say: the bigger the company, the smaller the environmental footprint. Almost always: sometimes the opposite is true: it depends on the economic sector.

Scaling laws, we suggest, can also be used to draft a simple benchmark to efficiently understand environmental corporate performance. The hereby proposed methodology should rely heavily on a vast and open-access database whereupon companies or regulators can estimate the current, sector specific benchmark. Ultimately that means that the more data is available and accessible, the higher the accuracy and transparency of the assessment. Measurement and transparency, is the way. Corporations should share their data and make them public, rather than convoluted and opaque ratings or indicators crafted by third, private parties.

Franco Ruzzenenti, Univerfsity of Groningen

I was born in Brescia-Italy, in March 20th 1975 and graduated in Environmental Economics at the University of Siena in 2001. After a period of almost two years in Oxford-UK, where he studied Biology and Chemistry as an Associate Student at Brooks University, I moved back to Italy to undertake a PhD Program in Environmental Chemistry, in 2003. In 2018 I won a Tenure Track position of an Assistant Professor at the Energy, Sustainability Research Institute Groningen (ESRIG-Faculty of Science and Engineering, University of Groningen). The call detailed the core of the area of research as: understanding “Energy and Industry Network Dynamics” to assess and explore the transition to a low-carbon society. The text of the call thrilled me extraordinarily. Perhaps because it contained some “keywords”, like networks, energy, industry systems and interdisciplinary fields. It was the harbor, in my opinion, for my research on Complexity and Energy. It has always been my conviction that the theme of complexity is of paramount importance to understand energy processes in the light of sustainability goals. Complexity is the common feature, though yet to be fully understood, of both anthropic and ecological systems. And complexity is the paradigm to reconcile them. Unfortunately, before I was appointed, the professor who wrote the call, Gerard Dijkema, passed away and I had to honor and responsibility to design research and a teaching program to address the “energy-industry network dynamics” thematic area.

In the domain of teaching, I designed an original course on complex system theories applied to energy systems, with a particular focus on network theory (with some hints of Agent Based Modelling) as an approach to complexity. In the domain of research, I developed the four following main research lines: 1) Theoretical and empirical investigation of the evolutionary nexus between energy and complexity, from a molecular scale up to the scale of production networks, with new models and metrics based on network theory; 2) The dynamic and transformative relationship between efficiency (and power) and energy use in human made systems; 3) the use of the digital space as a source of data and information to investigate firms and other societal actors; 4) approaches based on the concept of complexity, such as Agent Based Modelling, to model the uncertainty in the decision-making processes of economic actors. Currently I am associated professor in Energetics of Complex Systems at ESRIG, University of Groningen.