The backlash paradox of radical climate protests

Extreme actions turn people off the activists behind them—but may leave the broader climate movement stronger than before.

By Sarah DeWeerdt in Anthropocene

August 26, 2025

Groups that carry out extreme climate protests risk creating antipathy to themselves, but may increase concern about climate change more broadly, according to a new study. The findings add an empirical angle to the debate over disruptive tactics such as climate activists gluing themselves to property, throwing soup on paintings, or blocking bridges and roads that have emerged in recent years.

“We uncovered what we call the ‘climate activist’s dilemma,’” says study team member Jarren Nylund, a graduate student in social and environmental psychology at the University of Queensland in Australia.

“Disruptive climate protests may help raise awareness and motivate some people to act, but they can also alienate the public from the activists themselves,” he explains. “Importantly, we found no evidence that these tactics reduce support for the wider climate movement or the broader cause of climate action.”

Nylund and his colleagues conducted two studies. One included 178 Australian psychology students, and the other a politically representative sample of 511 people in the UK. In both studies, participants gave their impressions after reading descriptions of climate protests that varied in terms of protest tactics and targets.

The protests employed either moderate tactics (a peaceful rally in which protesters held placards) or extreme ones (activists blockaded property and defaced it with spray paint). They targeted either the headquarters of a fossil fuel corporation or a shopping center or department store open to the general public.

An understudied emotion packs a surprisingly large climate action punch

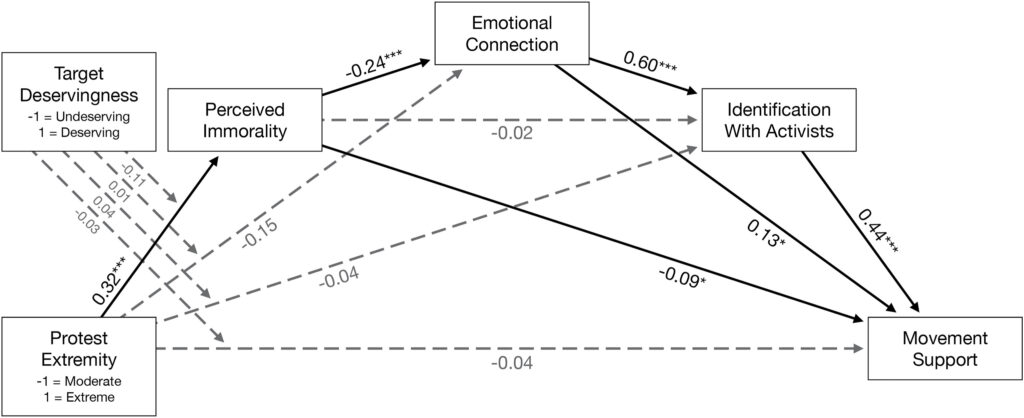

In both studies, participants perceived climate activists who engaged in disruptive protests as more immoral than those involved in moderate protests, the researchers report in the Journal of Environmental Psychology. They also felt less emotional connection and identification with extreme protestors, and said they had less support for the activist group.

Studies of other social movements have pointed to an “activist’s dilemma” whereby moderate protests struggle to capture public attention, while extreme protests garner negative attention – and wind up eroding support for the movement. But this dynamic seems to operate a bit differently in the case of climate change, the researchers found.

The second experiment revealed these nuances with more extensive, detailed questions about participants’ views of the protesting groups, the broader climate movement, and climate change in general. In this experiment, the extreme protests increased people’s concern about climate change and their intention to take action compared to the moderate protests.

“One thing that surprised me was that, unlike previous studies of extreme protest in other social movement contexts, we didn’t see a reduction in support for the broader climate cause,” Nylund says. “Instead, the decline in support was directed specifically at the activists using the disruptive tactics, not climate action itself.”

That is, people distinguished between the group doing the protest and the climate movement as a whole. A disruptive protest might spark backlash against the group involved, yet still increase support for climate action in the end.

“The public may see a clearer distinction between climate activists and the broader fight against climate change than in some other social movements, so negative views of climate protesters don’t necessarily spill over into opposition to the cause,” Nylund says. “It could also be that climate change has become such a widely recognized and urgent issue that people’s support for action is more resilient, even when they dislike how it’s being protested.”

The researchers expected that study participants would judge the protestors and their actions differently depending on whether protests targeted fossil fuel companies or the general public. But this wasn’t the case. “Participants may have seen both [fossil fuel company] employees and shoppers as fairly ordinary people, neither especially culpable nor blameless,” Nylund says. Or, they may not have seen the fossil fuel company as being particularly responsible for climate change.

The researchers plan follow-up experiments to better test how the “deservingness” of protest targets affects how people judge the protests.

More broadly, I’m interested in moving beyond the question of whether protest tactics work to understanding what specific attributes of a protest make it more likely to achieve outcomes that contribute to meaningful social change,” says Nylund. “My hope is that this line of research can equip organizers with clearer, evidence-based guidance for designing protest actions strategically.”

Source: Nylund J.L. et al. “The climate activist’s dilemma: Extreme protests reduce movement support but raise climate concern and intentions.” Journal of Environmental Psychology, 2025.

References

Badullovich et al., 2024N. Badullovich, D. Tucker, R. Amoako, P. Ansah, B. Davis, U.Horoszko, H. Zakiyyah, E. MaibachHow does public perception of climate protest influence support for climate action?Npj Climate Action, 3 (1) (2024), p. 16, 10.1038/s44168-023-00096-9View at publisherGoogle Scholar- BBC, 2022BBCExtinction rebellion: Activists block four London bridgesBBC (2022)https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-london-61120179Google Scholar

- Berglund et al., 2024O. Berglund, T.F. Brotto, C. Pantazis, C. Rossdale, R.P. CavalcantiCriminalisation and repression of climate and environmental protestsUniversity of Bristol (2024)https://crecep.blogs.bristol.ac.ukGoogle Scholar

- Berglund and Schmidt, 2020O. Berglund, D. SchmidtExtinction rebellion and climate change activism: Breaking the law to change the worldSpringer International Publishing (2020), 10.1007/978-3-030-48359-3View at publisherGoogle Scholar

- Brehm and Gruhl, 2024J. Brehm, H. GruhlIncrease in concerns about climate change following climate strikes and civil disobedience in GermanyNature Communications, 15 (1) (2024), p. 2916, 10.1038/s41467-024-46477-4View at publisherView in ScopusGoogle Scholar

- Bruneau et al., 2017E. Bruneau, D. Lane, M. SaleemGiving the underdog a leg up: A counternarrative of nonviolent resistance improves sustained third-party support of a disempowered groupSocial Psychological and Personality Science, 8 (7) (2017), pp. 746-757, 10.1177/1948550616683019View at publisherView in ScopusGoogle Scholar

- Buckley, 2022C. BuckleyThese groups want disruptive climate protests: Oil heirs are funding themNew York Times (2022)https://www.nytimes.com/2022/08/10/climate/climate-protesters-paid-activists.htmlGoogle Scholar

- Bugden, 2020D. BugdenDoes climate protest work? Partisanship, protest, and sentiment poolsSocius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World, 6 (2020), pp. 1-13, 10.1177/2378023120925949View at publisherGoogle Scholar

- Buzogány and Scherhaufer, 2023A. Buzogány, P. ScherhauferThe new climate movement: Organization, strategy, and consequencesH. Jörgens, C. Knill, Y. Steinebach (Eds.), Routledge handbook of environmental policy (1st ed.), Routledge (2023), pp. 358-380, 10.4324/9781003043843-30View in ScopusGoogle Scholar

- Carlsmith, 2006K.M. CarlsmithThe roles of retribution and utility in determining punishmentJournal of Experimental Social Psychology, 42 (2) (2006), pp. 437-451, 10.1016/j.jesp.2005.06.007View PDFView articleView in ScopusGoogle Scholar

- Carlsmith et al., 2002K.M. Carlsmith, J.M. Darley, P.H. RobinsonWhy do we punish? Deterrence and just deserts as motives for punishmentJournal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83 (2) (2002), pp. 284-299, 10.1037//0022-3514.83.2.284View in ScopusGoogle Scholar

- Choma and McKeown, 2019B.L. Choma, S. McKeownIntroduction to intergroup contact and collective action: Integrative perspectivesJournal of Theoretical Social Psychology, 3 (1) (2019), pp. 3-10, 10.1002/jts5.42View in ScopusGoogle Scholar

- Chryst et al., 2018B. Chryst, J. Marlon, S. van der Linden, A. Leiserowitz, E. Maibach, C.Roser-RenoufGlobal warming’s “six americas short survey”: Audience segmentation of climate change views using a four question instrumentEnvironmental Communication, 12 (8) (2018), pp. 1109-1122, 10.1080/17524032.2018.1508047View in ScopusGoogle Scholar

- Conversi, 2020D. ConversiThe ultimate challenge: Nationalism and climate changeNationalities Papers, 48 (4) (2020), pp. 625-636, 10.1017/nps.2020.18View in ScopusGoogle Scholar

- Dasch et al., 2024S.T. Dasch, M. Bellm, E. Shuman, M. van ZomerenThe radical flank: Curse or blessing of a social movement?Global Environmental Psychology, 2 (2024), Article e11121, 10.5964/gep.11121Google Scholar

- Eisenberg and Miller, 1987N. Eisenberg, P.A. MillerThe relation of empathy to prosocial and related behaviorsPsychological Bulletin, 101 (1) (1987), pp. 91-119, 10.1037/0033-2909.101.1.91View in ScopusGoogle Scholar

- Faul et al., 2007F. Faul, E. Erdfelder, A.-G. Lang, A. BuchnerG∗Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciencesBehavior Research Methods, 39 (2) (2007), pp. 175-191, 10.3758/BF03193146View in ScopusGoogle Scholar

- Feather, 1999N.T. FeatherValues, achievement, and justice: Studies in the psychology of deservingnessKluwer Academic Publishers (1999)https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/b108376Google Scholar

- Feinberg et al., 2020M. Feinberg, R. Willer, C. KovacheffThe activist’s dilemma: Extreme protest actions reduce popular support for social movementsJournal of Personality and Social Psychology, 119 (5) (2020), pp. 1086-1111, 10.1037/pspi0000230View in ScopusGoogle Scholar

- Fisher et al., 2023D.R. Fisher, O. Berglund, C.J. DavisHow effective are climate protests at swaying policy—And what could make a difference?Nature, 623 (7989) (2023), pp. 910-913, 10.1038/d41586-023-03721-zView in ScopusGoogle Scholar

- Gayle, 2023D. GayleInsulate Britain and just stop oil vow to continue disruptive actionThe Guardian (2023)https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2023/jan/02/insulate-britain-and-just-stop-oil-vow-to-continue-disruptive-actionGoogle Scholar

- Goetz et al., 2010J.L. Goetz, D. Keltner, E. Simon-ThomasCompassion: An evolutionary analysis and empirical reviewPsychological Bulletin, 136 (3) (2010), pp. 351-374, 10.1037/a0018807View in ScopusGoogle Scholar

- Grasso and Markowitz, 2015M. Grasso, E.M. MarkowitzThe moral complexity of climate change and the need for a multidisciplinary perspective on climate ethicsClimatic Change, 130 (3) (2015), pp. 327-334, 10.1007/s10584-014-1323-9View in ScopusGoogle Scholar

- Hafer, 2012C.L. HaferThe psychology of deservingness and acceptance of human rightsE. Kals, J. Maes (Eds.), Justice and conflicts: Theoretical and empirical contributions, Springer (2012), pp. 407-427, 10.1007/978-3-642-19035-3_25View in ScopusGoogle Scholar

- Haines, 2013H.H. HainesRadical flank effectsD. Della Porta, B. Klandermans, D. McAdam, D.A. Snow (Eds.), The wiley-blackwell encyclopedia of social and political movements (1st ed.), Wiley (2013), 10.1002/9780470674871.wbespm174Google Scholar

- Hallam, 2019R. HallamCommon sense for the 21st century: Only nonviolent rebellion can now stop climate breakdown and social collapseChelsea Green Publishing (2019)Google Scholar

- Han and Barnett-Loro, 2018H. Han, C. Barnett-LoroTo support a stronger climate movement, focus research on building collective powerFrontiers in Communication, 3 (2018), p. 55, 10.3389/fcomm.2018.00055View in ScopusGoogle Scholar

- Hayes, 2022A.F. HayesIntroduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach(3rd ed.), The Guilford Press (2022)Google Scholar

- Hornsey et al., 2021M.J. Hornsey, C.M. Chapman, D.M. OelrichsRipple effects: Can information about the collective impact of individual actions boost perceived efficacy about climate change?Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 97 (2021), Article 104217, 10.1016/j.jesp.2021.104217View PDFView articleView in ScopusGoogle Scholar

- Hornsey and Fielding, 2016M.J. Hornsey, K.S. FieldingA cautionary note about messages of hope: Focusing on progress in reducing carbon emissions weakens mitigation motivationGlobal Environmental Change, 39 (2016), pp. 26-34, 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2016.04.003View PDFView articleView in ScopusGoogle Scholar

- Hornsey et al., 2025M.J. Hornsey, J.L. Nylund, M. ThaiMorality, justice, and collective climate actionCurrent Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 64 (2025), Article 101541, 10.1016/j.cobeha.2025.101541View PDFView articleView in ScopusGoogle Scholar

- Kenward and Brick, 2024B. Kenward, C. BrickLarge-scale disruptive activism strengthened environmental attitudes in the United KingdomGlobal Environmental Psychology, 2 (2024), Article e11079, 10.5964/gep.11079Google Scholar

- King, 1963M.L. King Jr.The negro is your brotherThe Atlantic, 212 (1963), pp. 78-88CrossrefView in ScopusGoogle Scholar

- Kotyza et al., 2024P. Kotyza, I. Cabelkova, B. Pierański, K. Malec, B. Borusiak, L. Smutka, S.Nagy, A. Gawel, D. Bernardo López Lluch, K. Kis, J. Gál, J. Gálová, A. Mravcová, B.Knezevic, M. HlaváčekThe predictive power of environmental concern, perceived behavioral control and social norms in shaping pro-environmental intentions: A multicountry studyFrontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 12 (2024), Article 1289139, 10.3389/fevo.2024.1289139View in ScopusGoogle Scholar

- Kountouris and Williams, 2023Y. Kountouris, E. WilliamsDo protests influence environmental attitudes? Evidence from Extinction RebellionEnvironmental Research Communications, 6 (1) (2023), Article 11003, 10.1088/2515-7620/ac9aebGoogle Scholar

- Lau et al., 2021J.D. Lau, A.M. Song, T. Morrison, M. Fabinyi, K. Brown, J. Blythe, E.H. Allison, W.N. AdgerMorals and climate decision-making: Insights from social and behavioural sciencesCurrent Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 52 (2021), pp. 27-35, 10.1016/j.cosust.2021.06.005View PDFView articleView in ScopusGoogle Scholar

- Lee et al., 2023H. Lee, K. Calvin, D. Dasgupta, G. Krinner, A. Mukherji, P. Thorne, C. Trisos, J.Romero, P. Aldunce, K. Barrett, G. Blanco, W.W.L. Cheung, S.L. Connors, F. Denton, A.Diongue-Niang, D. Dodman, M. Garschagen, O. Geden, B. Hayward, …, Z. ZommersSynthesis report of the IPCC sixth assessment reportIntergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2023)https://www.ipcc.ch/report/sixth-assessment-report-cycle/Google Scholar

- Leiserowitz et al., 2023A. Leiserowitz, E. Maibach, S. Rosenthal, J. Kotcher, E. Goddard, J.Carman, M. Verner, M. Ballew, J. Marlon, S. Lee, T. Myers, M. Goldberg, N.Badullovich, K. ThierGlobal warming’s six Americas, fall 2023Yale Program on Climate Change Communication (2023)https://climatecommunication.yale.edu/publications/global-warmings-six-americas-fall-2023/Google Scholar

- Lerner, 1980M.J. LernerThe belief in a just world: A fundamental delusionSpringer US (1980), 10.1007/978-1-4899-0448-5Google Scholar

- Lupfer and Gingrich, 1999M.B. Lupfer, B.E. GingrichWhen bad (good) things happen to good (bad) people: The impact of character appraisal and perceived controllability on judgments of deservingnessSocial Justice Research, 12 (3) (1999), pp. 165-188, 10.1023/A:1022189200464View in ScopusGoogle Scholar

- Malm, 2021A. MalmHow to blow up a pipeline: Learning to fight in a world on fireVerso (2021)Google Scholar

- Menzies et al., 2023R.E. Menzies, M.B. Ruby, I. Dar-NimrodThe vegan dilemma: Do peaceful protests worsen attitudes to veganism?Appetite, 186 (2023), Article 106555, 10.1016/j.appet.2023.106555View PDFView articleView in ScopusGoogle Scholar

- Morrison et al., 2022T.H. Morrison, W.N. Adger, A. Agrawal, K. Brown, M.J. Hornsey, T.P.Hughes, M. Jain, M.C. Lemos, L.H. McHugh, S. O’Neill, D. Van BerkelRadical interventions for climate-impacted systemsNature Climate Change, 12 (12) (2022), pp. 1100-1106, 10.1038/s41558-022-01542-yView in ScopusGoogle Scholar

- Neumann et al., 2022C. Neumann, S.K. Stanley, Z. Leviston, I. WalkerThe six Australias: Concern about climate change (and global warming) is risingEnvironmental Communication, 16 (4) (2022), pp. 433-444, 10.1080/17524032.2022.2048407View in ScopusGoogle Scholar

- Norris, 2011P. NorrisDemocratic deficit: Critical citizens revisitedCambridge University Press (2011)Google Scholar

- Nugent, 2020C. NugentA revolution’s evolution: Inside Extinction Rebellion’s attempt to reform its climate activismTime (2020)https://time.com/5864702/extinction-rebellion-climate-activism/Google Scholar

- Office for National Statistics, 2023Office for National StatisticsWorries about climate change, Great Britain: September to October 2022Office for National Statistics (2023)https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/wellbeing/articles/worriesaboutclimatechangegreatbritain/septembertooctober2022Google Scholar

- Opotow, 1990S. OpotowMoral exclusion and injustice: An introductionJournal of Social Issues, 46 (1) (1990), pp. 1-20, 10.1111/j.1540-4560.1990.tb00268.xView in ScopusGoogle Scholar

- Opp, 2009K.-D. OppTheories of political protest and social movements A multidisciplinary introductionCritique, and synthesis, Routledge (2009)Google Scholar

- Orazani and Leidner, 2019S.N. Orazani, B. LeidnerThe power of nonviolence: Confirming and explaining the success of nonviolent (rather than violent) political movementsEuropean Journal of Social Psychology, 49 (4) (2019), pp. 688-704, 10.1002/ejsp.2526View in ScopusGoogle Scholar

- Orazani et al., 2021N. Orazani, N. Tabri, M.J.A. Wohl, B. LeidnerSocial movement strategy (nonviolent vs. violent) and the garnering of third‐party support: A meta‐analysisEuropean Journal of Social Psychology, 51 (4–5) (2021), pp. 645-658, 10.1002/ejsp.2722View in ScopusGoogle Scholar

- Ortiz et al., 2022I. Ortiz, S. Burke, M. Berrada, H. Saenz CortésWorld protests: A study of key protest issues in the 21st CenturySpringer International Publishing (2022), 10.1007/978-3-030-88513-7Google Scholar

- Ostarek et al., 2024M. Ostarek, B. Simpson, C. Rogers, J. OzdenRadical climate protests linked to increases in public support for moderate organizationsNature Sustainability (2024), 10.1038/s41893-024-01444-1Google Scholar

- Oveis et al., 2010C. Oveis, E.J. Horberg, D. KeltnerCompassion, pride, and social intuitions of self-other similarityJournal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98 (4) (2010), pp. 618-630, 10.1037/a0017628View in ScopusGoogle Scholar

- Palmeira et al., 2022M. Palmeira, M. Koo, H.-A. SungYou deserve the bad (or good) service: The role of moral deservingness in observers’ reactions to service failure (or excellence)European Journal of Marketing, 56 (3) (2022), pp. 653-676, 10.1108/EJM-09-2020-0659View in ScopusGoogle Scholar

- Patterson and Mann, 2022S. Patterson Jr., M.E. MannPublic disapproval of disruptive climate change protestsUniversity of Pennsylvania (2022)Center for Science, Sustainability, and the Mediahttps://web.sas.upenn.edu/pcssm/commentary/public-disapproval-of-disruptive-climate-change-protests/Google Scholar

- Pepitone and L’Armand, 1996A. Pepitone, K. L’ArmandThe justice and injustice of life eventsEuropean Journal of Social Psychology, 26 (4) (1996), pp. 581-597, 10.1002/(SICI)1099-0992(199607)26:43.0.CO;2-OView in ScopusGoogle Scholar

- Piven and Cloward, 1979F.F. Piven, R.A. ClowardPoor people’s movements: Why they succeed, how they failVintage Books (1979)Google Scholar

- Pörtner et al., 2022H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M.M.B. Tignor, E. Poloczanska, K.Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem, B.RamaClimate change 2022: Impacts, adaptation and vulnerability (Working group II contribution to the sixth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on climate Change)Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2022)https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/Google Scholar

- Rogers, 2019N. RogersActivists are using the climate emergency as a new legal defence to justify law-breakingThe Conversation (2019)https://theconversation.com/activists-are-using-the-climate-emergency-as-a-new-legal-defence-to-justify-law-breaking-122949Google Scholar

- Shukla et al., 2022P.R. Shukla, J. Skea, A. Reisinger, R. Slade, R. Fradera, M. Pathak, A.A.Khourdajie, M. Belkacemi, R. van Diemen, A. Hasija, G. Lisboa, S. Luz, J. Malley, D.McCollum, S. Some, P. VyasClimate change 2022: Mitigation of climate change (Working group III contribution to the sixth report of the Intergovernmental Panel on climate Change)Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2022)https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg3/Google Scholar

- Shuman et al., 2021E. Shuman, T. Saguy, M. van Zomeren, E. HalperinDisrupting the system constructively: Testing the effectiveness of nonnormative nonviolent collective actionJournal of Personality and Social Psychology, 121 (4) (2021), pp. 819-841, 10.1037/pspi0000333View in ScopusGoogle Scholar

- Simpson et al., 2018B. Simpson, R. Willer, M. FeinbergDoes violent protest backfire? Testing a theory of public reactions to activist violenceSocius, 4 (2018), 10.1177/2378023118803189Google Scholar

- Simpson et al., 2022B. Simpson, R. Willer, M. FeinbergRadical flanks of social movements can increase support for moderate factionsPNAS Nexus, 1 (3) (2022), Article pgac110, 10.1093/pnasnexus/pgac110View in ScopusGoogle Scholar

- Smith, 2019M. SmithConcern for the environment at record highsYouGov UK (2019)https://yougov.co.uk/politics/articles/23691-concern-environment-record-highsGoogle Scholar

- Sommet et al., 2023N. Sommet, D.L. Weissman, N. Cheutin, A.J. ElliotHow many participants do I need to test an interaction? Conducting an appropriate power analysis and achieving sufficient power to detect an interactionAdvances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science, 6 (3) (2023), Article 25152459231178728, 10.1177/25152459231178728Google Scholar

- Stellar et al., 2014J. Stellar, M. Feinberg, D. KeltnerWhen the selfish suffer: Evidence for selective prosocial emotional and physiological responses to suffering egoistsEvolution and Human Behavior, 35 (2) (2014), pp. 140-147, 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2013.12.001View PDFView articleView in ScopusGoogle Scholar

- Stephan and Chenoweth, 2008M.J. Stephan, E. ChenowethWhy civil resistance works: The strategic logic of nonviolent conflictInternational Security, 33 (1) (2008), pp. 7-44, 10.1162/isec.2008.33.1.7Google Scholar

- Thomas and Louis, 2014E.F. Thomas, W.R. LouisWhen will collective action be effective? Violent and non-violent protests differentially influence perceptions of legitimacy and efficacy among sympathizersPersonality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 40 (2) (2014), pp. 263-276, 10.1177/0146167213510525View in ScopusGoogle Scholar

- Trivers, 1971R.L. TriversThe evolution of reciprocal altruismThe Quarterly Review of Biology, 46 (1) (1971), pp. 35-57, 10.1086/406755Google Scholar

- Tufekci, 2017Z. TufekciTwitter and tear gas: The power and fragility of networked protestYale University Press (2017)Google Scholar

- Uhlmann et al., 2013E.L. Uhlmann, L.(L.). Zhu, D. TannenbaumWhen it takes a bad person to do the right thingCognition, 126 (2) (2013), pp. 326-334, 10.1016/j.cognition.2012.10.005View PDFView articleView in ScopusGoogle Scholar

- Urban, 2024M.C. UrbanClimate change extinctionsScience, 386 (6726) (2024), pp. 1123-1128, 10.1126/science.adp4461View in ScopusGoogle Scholar

- van Zomeren and Iyer, 2009M. van Zomeren, A. IyerIntroduction to the social and psychological dynamics of collective actionJournal of Social Issues, 65 (4) (2009), pp. 645-660, 10.1111/j.1540-4560.2009.01618.xView in ScopusGoogle Scholar

- van Zomeren et al., 2008M. van Zomeren, T. Postmes, R. SpearsToward an integrative social identity model of collective action: A quantitative research synthesis of three socio-psychological perspectivesPsychological Bulletin, 134 (4) (2008), pp. 504-535, 10.1037/0033-2909.134.4.504View in ScopusGoogle Scholar

- van Zomeren et al., 2012M. van Zomeren, T. Postmes, R. SpearsOn conviction’s collective consequences: Integrating moral conviction with the social identity model of collective actionBritish Journal of Social Psychology, 51 (1) (2012), pp. 52-71, 10.1111/j.2044-8309.2010.02000.xView in ScopusGoogle Scholar

- Walgrave and Vliegenthart, 2012S. Walgrave, R. VliegenthartThe complex agenda-setting power of protest: Demonstrations, media, parliament, government, and legislation in Belgium, 1993-2000Mobilization: International Quarterly, 17 (2) (2012), pp. 129-156, 10.17813/maiq.17.2.pw053m281356572hView in ScopusGoogle Scholar

- Wasow, 2020O. WasowAgenda seeding: How 1960s black protests moved elites, public opinion and votingAmerican Political Science Review, 114 (3) (2020), pp. 638-659, 10.1017/S000305542000009XView in ScopusGoogle Scholar

- Weiner, 1995B. WeinerJudgments of responsibility: A foundation for a theory of social conduct(1st ed.), Guilford Press (1995)Google Scholar

- Wien and Elmelund-Præstekær, 2009C. Wien, C. Elmelund-PræstekærAn anatomy of media hypes: Developing a model for the dynamics and structure of intense media coverage of intense media coverage of single issuesEuropean Journal of Communication, 24 (2) (2009), pp. 183-201, 10.1177/0267323108101831View in ScopusGoogle Scholar

- Wright, 2010S.C. WrightCollective action and social changeJ.F. Dovidio, M. Hewstone, P. Glick, V.M. Esses (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of prejudice, stereotyping and discrimination, SAGE Publications Ltd (2010), pp. 577-596, 10.4135/9781446200919.n35View in ScopusGoogle Scholar

- Wright et al., 1990S.C. Wright, D.M. Taylor, F.M. MoghaddamResponding to membership in a disadvantaged group: From acceptance to collective protestJournal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58 (6) (1990), pp. 994-1003, 10.1037/0022-3514.58.6.994View in ScopusGoogle Scholar

- YouGov, ndYouGov UK. (n.d.). The most important issues facing the country. https://yougov.co.uk/topics/society/trackers/the-most-important-issues-facing-the-country.Google Scholar

- Yu et al., 2023H. Yu, J. Chen, B. Dardaine, F. YangMoral barrier to compassion: How perceived badness of sufferers dampens observers’ compassionate responsesCognition, 237 (2023), 10.1016/j.cognition.2023.105476105476–105476Google Scholar