Succesfully deploying offshore renewable energy

Image WWF report: Figure 2: Projected installation of wind energy capacity (gigawatts) 2022-2026,

Source: Global Wind Energy Council, Global Wind Report 2023

The Global Wind Energy Council expects 680 GW of wind capacity to be added globally between 2023 and 2027, of which 130 GW will be offshore. This represents more than half of the 1200 GW of renewable energy needed by 2030 according to the “Net Zero Emissions by 2050” scenario of the International Energy Agency.13 Onshore wind in China will continue to lead installations with 300 GW, followed by Europe with nearly 100 GW. It should be noted, however, that the achievement of this projected growth in wind energy capacity depends on multiple factors including available infrastructure, natural resources, work force and project approval processes, to name a few.

This scale of development is urgently needed to meet our growing energy needs in line with keeping global warming under 1.5°C as set in the Paris Agreement. However, it is equally vital to ensure that this scale of energy infrastructure deployment will contribute toward a just energy transformation embedded in a nature- positive future.

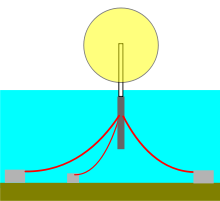

Operational offshore floating wind turbine energy farms

The world’s first full-scale floating wind turbine, the 2.3 MW Hywind, being assembled in the Åmøy Fjord near Stavanger, Norway in 2009, before deployment in the North Sea

Blue H Technologies – World’s first floating wind turbine (80 kW), installed in waters 113 metres (371 ft) deep in 2007, 21.3 kilometres (13.2 mi) off the coast of Apulia, Italy

The world’s second full-scale floating wind turbine (and first to be installed without the use of heavy-lift vessels), the 2 MW WindFloat, about 5 km offshore of Aguçadoura, Portugal

A single floating cylindrical spar buoy moored by catenary cables. Hywind uses a ballasted catenarylayout that adds 60 tonne weights hanging from the midpoint of each anchor cable to provide additional tension.

WWF report: Meeting the climate and biodiversity targets by 2030 as part of a just energy transformation and a nature-positive future

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Climate change and biodiversity collapse are the two greatest threats facing both humans and nature today. These crises are intertwined, compound global inequalities, and must be addressed together.

Covering over 70% of the surface of our planet, our ocean must not be forgotten

in how we transform our energy system. It is crucial to effectively plan, protect, manage and strengthen the resilience of marine and coastal ecosystems hand in hand with scaling up responsible renewable energy solutions. In the context of WWF’s Global Policy Energy Framework, this position presents recommendations

for the faster, greener and fairer deployment of offshore renewable energy as part of a just energy transformation and a nature-positive future.

Offshore renewable energy technologies are vital to a successful energy transition, yet there is important work to be done to ensure that they are designed and implemented without further undermining ocean

health and resilience. As a form of industrial infrastructure, the design, deployment, operation and decommissioning of offshore

renewables must avoid, reduce and mitigate any negative effects as much as possible, while taking steps to enhance, enrich and

restore nature. This means that offshore renewable projects should not be developed within marine protected and conserved areas (MPCAs) or in other areas of particular importance for biodiversity, ecosystems and ecosystem services.

Effective implementation of offshore renewable energy projects, achieved through thoughtful planning and meaningful stakeholder

consultations, requires governments to consider all threats and pressures on marine and coastal ecosystems (and their cumulative impacts) in order to make sound decisions. Ecosystem-based maritime spatial planning (MSP) is key for selecting the best areas for offshore renewable energy development in an inclusive and participatory manner.

A fair and just energy transformation plays a critical role in how we will reach our climate and biodiversity targets. We have an opportunity to boost employment opportunities and contribute to a sustainable blue economy while protecting, strengthening and restoring nature – let’s seize it.

GLOBAL INSTALLED OFFSHORE WIND CAPACITY IS EXPECTED TO REACH 630 GW BY 2050, UP FROM 40 GW IN 2020

Source: AR3T Action Framework, Science Based Targets for Nature, Science Based Targets Network, 2020

SOCIAL JUSTICE IN THE JUST ENERGY TRANSFORMATION

Actions that contribute to a nature-positive future aim to tackle the climate and biodiversity crises in tandem, while ensuring a socially equitable and just energy transition.18 Our ocean is a public good that should be managed in the public interest.

Seas and coasts are often crowded and contested spaces, with multiple industries and stakeholders with overlapping rights and interests. For example, Indigenous Peoples and local communities may have high dependencies on ocean and coastal resources in tandem with strong cultural connections, making it important to recognize their rights and aspirations. In this context, the social component of the nature-positive deployment of offshore renewables requires the same attention and diligence given to the sector’s technical and economic feasibility. (For more information, please consult the Technical Annex.)

Avoiding the creation of new injustices and, in the best cases, addressing existing injustices are essential when implementing a just energy transformation. This process involves sharing the benefits of sustainable transitions widely, while seeking to minimize and avoid negative impacts on the most vulnerable.19

Depending on the process, the social impacts of energy projects can be positive – in terms of poverty alleviation, creation of local jobs

and community networks, workforce training and procurement20 – or negative – such as violence, displacement of local communities and exacerbation of inequalities, especially between genders, those who are more or less socially dominant, and for marginalized communities.

(For more information, please consult the Technical Annex.) In this regard, a context-specific transition plan is necessary to make sure the overall impacts of the transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy are positive and socially fair. Examples include Just Energy Transition Plans, such as those in South Africa22 and Indonesia,23 and the Territorial Just Transition Plans of the European Union.24

The just transformation in the energy sector must therefore focus on the systemic changes needed to simultaneously deliver on climate

and nature targets and the UN Sustainable Development Goals in order to achieve a more equitable, sustainable and climate safe world

for all. Together, climate justice (as a core principle) and just transitions (as planned processes specific to sectors and/or places) are required to enable a truly just global energy transformation.

Climate justice is the principle that the burden of climate change including the costs of mitigation and adaptation are shared fairly, both internationally and intergenerationally, and that climate action upholds the rights of all.

SUCCESSFULLY DEPLOYING OFFSHORE RENEWABLE ENERGY FOR NATURE, CLIMATE AND PEOPLE

The international financial and administrative systems that are expected to manage energy transitions in line with social justice principles can be biased, too slow or too complex, and unresponsive to the needs and circumstances of countries and communities. In addition, if they operate as they have in the past, they will further increase existing inequalities between those who can, for example, afford to pay for energy, find employment and/or be involved in decision- making processes and those who cannot.25 This makes due consideration for social and economic aspects of offshore renewable energy projects crucial, and for equity in how benefits are shared along the supply chain. (For more information, please consult the Technical Annex.) Clarity on these two components will support the deployment of renewable energy in ways that are gender-responsive, rewarding and beneficial for project proponents, Indigenous Peoples and local communities, and therefore more durably contribute to a nature-positive future.

WWF RECOMMENDATIONS

We are at a pivotal moment in our history to

secure a liveable and sustainable future for all life on our planet.

Nature and climate are two sides of the same coin and they cannot be seen separately or as being in opposition. It is impossible to stop climate change, mitigate global temperature rise and adapt to changes already taking place (current global warming is at around 1.1°C at the time of preparing this document), without thriving nature, our ally in the fight against climate breakdown.26 WWF sees any narrative of ‘climate versus nature’ as both dangerous and counterproductive. Nature is fundamental to successful climate mitigation, adaptation and resilience. And climate change mitigation is critical in halting biodiversity loss.

To reach our climate and biodiversity targets, it is crucial to effectively plan, protect, manage and strengthen the resilience of marine and coastal ecosystems hand in hand with the need to scale up responsible renewable energy solutions. This means that the design, deployment, operation and decommissioning of offshore renewables and related infrastructure must avoid, reduce and mitigate negative effects as much as possible and take action to enhance, enrich and restore nature. Our climate and biodiversity targets must be met jointly, and must be achieved through thoughtful planning and meaningful consultations. We have an opportunity to make a fair and just energy transformation that can generate employment opportunities and contribute to the sustainable blue economy while protecting, strengthening and restoring nature – let’s seize it.

Within the scope of WWF’s Energy Vision,27 keeping global warming below 1.5°C requires urgent action from governments to drive the deployment of offshore renewables as part of a just energy transformation and nature-positive future.

ASKS FOR GOVERNMENT

MOVE FASTER:

Implement smart site selection through an ecosystem-based maritime spatial planning

(MSP) process, with proper energy planning following

a conservation and mitigation hierarchy and in line with relevant national, regional and international legislation and biodiversity targets (e.g., the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework) and relevant regional conservation initiatives (e.g., Jurisdictional Initiatives). This should help facilitate the effective engagement of public and private stakeholders while being mindful of and addressing the risks involved, such as biodiversity impacts, thereby helping to reduce conflicts, facilitate timely approvals and improve environmental outcomes.

Foster cooperation in the planning, permitting, tendering and auctioning processes to ensure a coordinated, cohesive, environmentally conscious and multi-sectorally engaged approach at sea basin level with the aim to decrease operators’ administrative burden related to multiple standards between countries and regions while lowering environmental impacts and fostering innovation.

Allocate additional resources for improved permitting mechanisms to foster timely approvals nationally and regionally that support the deployment of offshore renewables following appropriate environmental and social impact assessments.

Increase training in offshore renewables for authorities and sector employees, including in

the transfer of some marine-based technical skills from the offshore oil and gas industry to the offshore

wind sector to accelerate commercialization. Local-level capacity building, resources and administrative support

for municipalities will be critical for planning and approval authorities to undertake MSP, EIAs and approval functions for offshore renewable energy efficiently and effectively. This should include training to support and facilitate the effective engagement of public and private stakeholders

to ensure planning delivers clear benefits to local communities and a just transition.

Reduce risk by ensuring regulatory certainty, providing insurance and offtake/demand guarantees, particularly for capital-intensive offshore renewable investments such as wind energy.

Invest in research, technology development and demonstration projects to help make all forms

of ocean-based renewable energy – including

wind, wave, tidal, current, thermal and solar – cost- competitive, accessible to all and environmentally sustainable.

GO GREENER:

Mandate systematic, stringent and participatory SEAs as well as EIAs for new offshore renewable plans and projects. These assessments should clearly define mitigation measures that minimize harmful effects on ecosystems and species and how to deal directly with degraded species/habitats. Those assessments must also consider cumulative impacts of all activities present in the wider project area, and impacts of service and repair activities by port infrastructure and the routing of cables.

Develop an effective pathway for proper decommissioning of harmful activities such

as offshore oil and gas infrastructure to reduce cumulative impacts of all at-sea activities, i.e., within the ecosystem-based MSP process.

Invest in early nature-sensitivity mapping for

smart site-selection to reduce negative impacts on marine environments within an ecosystem-based MSP processes

to ensure robust data-collection technology is used to prevent renewable energy projects from being proposed within current or planned protected

and conserved areas, or within other areas of particular importance for biodiversity, ecosystems and services. These include ecological corridors, migration routes of marine species and birds, fish spawning and rearing areas, as well as areas with high natural carbon uptake and storage such as seagrasses, saltmarshes, mangroves, reefs and other areas critical for coastal protection and resilience.

Site selection should prioritize already-degraded areas and/or areas previously allocated for maritime activities that are being phased out, such as oil and gas leases. This will prevent further harmful impacts to marine ecosystems, while proper long-term planning of offshore renewable activities can in fact contribute to nature restoration.

Explore potential for designating multi-use zones

alongside other legal sector-based requirements in MSP processes, with the aim to increase functionality and reduce environmental pressures outside these areas, and bring cost-effective solutions. If not properly allocated and managed, however, they can also bring conflicts of interest and risks to the marine environment and sectors involved. Clear communication and coordination among relevant stakeholders is therefore needed to identify potential risks and negative impacts and identify areas where other sectors can coexist (or not) to ensure that maritime activities can be carried out safely and within ecological limits, while enlarging and/or ensuring impact-free zones.

Reduce demand for raw materials and promote circularity through structural policies, as well as the use of secondary commodities, based on circular economy principles across the manufacturing, transport, installation and decommissioning stages of offshore renewable energy projects. Projects should optimize energy efficiency and maximize reuse of materials to avoid and minimize social and environmental impacts across the supply chain. This should help ensure that the accelerated deployment of renewable energy is not dependent on virgin sources whose extraction is harmful to the environment, nor impacted by international conflicts and delays in production.

Collaborate across borders and exclusive economic zones to reinforce transnational responsibilities for understanding marine ecosystems on a regional basis, and cooperate to increase efficiency of renewable energy deployment and energy-saving strategies.

Include and heavily weight non-price auction criteria (i.e., environmental and social criteria) in procurement and tendering processes to foster innovative solutions and advance best practices with the aim of avoiding impacts on marine ecosystems and preventing further climate injustice.

Reinforce data collection on impacts to biodiversity, with the requirement that the energy industry monitor relevant environmental information

on marine ecosystems and species in the long term to better understand the effects on species and ecosystems. This should include areas that are closed for fisheries, as common regulatory practice for safety reasons, and that regulators and companies should monitor for changes in fish populations and ecosystem health (including seafloor habitats) as a consequence of wind farm exclusion zones. These can be seen as passive refuges and recovery areas for benthic species and fish, potentially resulting in higher densities and larger animals.

Follow conservation hierarchy principles and implement a mitigation hierarchy (see Figures

on pages 10-11 and 12-13), and ensure that additional measures to enhance marine ecosystems are in place (i.e., by active and/or passive restoration).

Provide environmental authorities with the mandate, sufficient capacity and adequate funding to effectively avoid and manage any negative consequences to nature that may be caused by actions proposed in projects, and to clean up and restore any areas that degrade as a result of project infrastructure and management.

BE FAIRER:

Engage in meaningful stakeholder and rights- holder consultations along all renewable

energy development processes and throughout project monitoring, with particular attention

to Indigenous Peoples and local communities, and other groups who might bear higher costs. Consultation is crucial, especially in areas with highly fragmented or contested ownership, or situations where the community has not been sufficiently consulted during the MSP process. This must include free, prior and informed consent, in the case of Indigenous Peoples, and participatory planning and approval processes involving local communities. Effective stakeholder consultation can help facilitate local value creation, including in the form of job creation and potential co-ownership.

Undertake a social impact assessment nationally or through project-specific calls to create jobs, understand how to transfer skills, empower local communities, and enhance the position of women, minority groups and other disadvantaged or marginalized members of society with the aim to repair injustices.

Address stakeholder and rights-holders concerns about the ecosystem services and social impacts of offshore renewable energy projects during auctioning, as doing so delivers important benefits such as increasing local acceptance of awarded projects and social inclusion that can steer funding from investors who have strongly integrated social standards.

Clean-up costs for decommissioning an energy project, disposing of materials and subsequent nature restoration must be included in the financial assessment of a development proposal, and the developer must guarantee sufficient funds for all phases of this work to ensure Indigenous Peoples, local communities and tax payers do not bear the financial burden.

Seek out developers who demonstrate that they prioritize equal opportunities, representation and inclusion of women and minority groups.

Ensure citizens’ rights to be informed, to freedom of expression and to give an opinion during public consultation processes are respected to deliver meaningful stakeholder consultations that will result in economic, social and environmental benefits in the long term.

ASKS FOR OFFHORE RENEWABLES INDUSTRY

MOVE FASTER:

Establish corporate commitments that contribute to a nature-positive future, including clear and ambitious conservation targets, aligned with national and international biodiversity, nature protection and nature restoration commitments.

Regularly monitor, assess, and transparently disclose risks, dependencies and impacts on biodiversity to progressively reduce negative impacts on biodiversity, increase positive impacts, reduce biodiversity- related risks and promote actions to ensure sustainable patterns of production in accordance with target 15 of the

Develop offshore renewable energy projects with due consideration for life cycle consequences, including a plan for the eventual decommissioning of structures, infrastructure and recycling materials at end of life. This will not only minimize litter and contaminants on the seafloor, but also reduce annual mineral demand. These outcomes are key to both tackle the biodiversity crisis and support rapid deployment of renewable energy, as resource constraints can make the energy transition slower and more expensive.

GO GREENER:

Prevent deploying offshore renewables in current or planned marine protected and conserved

areas, Indigenous sacred sites, and other areas of particular importance for biodiversity, ecosystems and services. These include ecological corridors, migration routes of marine species and birds, fish spawning and rearing areas, as well as areas with high natural carbon uptake and storage such as seagrasses, saltmarshes, mangroves, reefs and other areas critical for coastal protection and resilience. Any damage to or degradation of these areas will have greater impacts on ocean ecosystems and thus on stakeholders outside of the energy sector; this could also bring reputational risks and social resistance to the deployment of renewables.

Ensure traceability of raw materials affiliated with projects and account for supply chain impacts within broader corporate commitments. This will

be a first step toward minimizing environmental destruction and further biodiversity loss, demonstrating sustainable business practice, which is key for investors and will help

to avoid reputational risks and societal backlash against the deployment of renewables.

Avoid and minimize all forms of pollution

(including plastic, chemical, noise and metal pollution)

during construction, operation, maintenance and decommissioning phases of offshore renewable energy projects, going beyond the legal minimum set in relevant markets. This will demonstrate and be recognized as sustainable business practice, which is key for investors.

Prioritize avoiding adverse impacts on habitats, species and the functioning of marine ecosystems in the planning, design, construction, operation, management and eventual decommissioning of offshore renewable projects, including cumulative and compounding impacts within temporal and spatial scales, through the application of science-based best practice approaches and technology. Where impacts cannot be avoided, apply a conservation and mitigation hierarchy sequentially to reduce impacts and restore and regenerate nature.

Freely share non-sensitive developer data to improve baseline information and monitoring of renewable energy project impacts. This will improve understanding of the sector’s interactions with marine ecosystems and species, informing future MSP processes, scientific research and policy development.

BE FAIRER:

Proactively consider potential cumulative social and environmental impacts of both current and planned future projects to avoid negative impacts and thus any conflicts that could delay energy deployment processes.

Establish social safeguards to avoid discrimination and ensure energy projects are socially positive for local communities – with their full and free consent – such as by enhancing local access to clean energy and creating jobs.

Ensure that all projects leverage ecosystem-

based MSP and robust and proactive stakeholder engagement to avoid impacts in marine protected areas, as well as areas of high ecological value, with high biodiversity and sensitive habitats.

Establish a clear link between impact monitoring and materiality of social and environmental impacts to reduce harmful impacts to communities, habitats and biodiversity, thus reducing reputational risks.

REFERENCES

- WWF, A Global Goal for Nature – Nature Positive by 2030 https:// 16. www.naturepositive.org/

- McKinsey, 2022, How to succeed in the expanding global offshore

wind market https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/electric-power- and-natural-gas/our-insights/how-to-succeed-in-the-expanding- 17. global-offshore-wind-market#/ - Sovacool et al., 2021, The hidden costs of energy and mobility:

A global meta-analysis and research synthesis of electricity

and transport externalities, https://www.researchgate.net/ publication/349489647_The_hidden_costs_of_energy_and_ 18. mobility_A_global_meta-analysis_and_research_synthesis_of_ electricity_and_transport_externalities - IPCC, 2023, AR6 Synthesis Report: Climate Change 2023, https:// 19. www.ipcc.ch/report/sixth-assessment-report-cycle/; IPBES, 2019,

Global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of

the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3831673

World Economic Forum, 2020, 395 Million New Jobs by 2030 if Businesses Prioritize Nature, Says World Economic Forum https:// www.weforum.org/press/2020/07/395-million-new-jobs-by-2030-if- businesses-prioritize-nature-says-world-economic-forum/

Vermont Law School, Institute for Energy and the Environmental, The Nature Conservancy, 2023, Using Non-Price Criteria in State Offshore Wind Solicitations to Advance Net Positive Biodiversity Goals https://www.vermontlaw.edu/sites/default/files/2023-06/iee- tnc_offshore-wind-report_20230606_1644.pdf

IUCN, 2022, Towards an IUCN nature-positive approach: a working paper https://www.iucn.org/resources/file/summary- towards-iucn-nature-positive-approach-working-paper

WWF, 2021, WWF Discussion Paper – Just Energy Transformation https://climate-pact.europa.eu/system/ files/2022-09/wwf_discussion_paper___just_energy_ transformation.pdf

- FAO, 2022, The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture (SOFIA) https://www.fao.org/publications/home/fao-flagship-publications/the- state-of-world-fisheries-and-aquaculture/en

- WWF, Ocean-Climate Solutions https://wwf.panda.org/discover/ our_focus/oceans_practice/ocean_and_climate/

- United Nations, 2016, Aesthetic, Cultural, Religious and Spiritual Ecosystem Services Derived from the Marine Environment https:// www.un.org/depts/los/global_reporting/WOA_RPROC/Chapter_08. pdf

- United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity, 2022, COP15: Final Text Of Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework https://www.cbd.int/article/cop15-final-text-kunming-montreal- gbf-221222

- United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity, Conference

Of The Parties To The Convention On Biological Diversity, 2022, Decision Adopted By The Conference Of The Parties To The Convention On Biological Diversity https://www.cbd.int/doc/decisions/ cop-15/cop-15-dec-04-en.pdf - Taormina, B., 2019, Potential impacts of submarine power cables from marine renewable energy projects on benthic communities https://theses.hal.science/tel-03078936

- Schnitzer et al., 2014, Microgrids for Rural Electrification: A critical review of best practices based on seven case studies; Nathwani J, Kammen D, 2020, Affordable Energy for Humanity:

A Global Movement to Support Universal Clean Energy Access Kemabonta T, Kammen D, 2021, A community based approach to universal energy access, https://rael.berkeley.edu/wp-content/ uploads/2021/02/Kemabonta-Kammen-Universal-Energy-Access- Electricity-Journal-2021.pdf - H. Snyder, 2019, Literature review as a research methodology: an overview and guidelines, J. Bus. Res. 104 (2019) 333–339;Stern.J., 2021, Immigration and Human Rights Law Review, Pipeline of Violence: The Oil Industry and Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women https://lawblogs.uc.edu/ihrlr/2021/05/28/ pipeline-of-violence-the-oil-industry-and-missing-and-murdered- indigenous-women/USAID and IUCN, 2018, Advancing Gender In The Environment: Making The Case For Gender Equality In Large-Scale Renewable Energy Infrastructure Development https://www.globalwomennet. org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/IUCN-USAID-Making_the_case_ for_INFRASTRUCTURE.pdf;

Vicente, Pedro C., 2010, Journal of Development Economics, Does Oil Corrupt? Evidence from a Natural Experiment in West Africa http://www.pedrovicente.org/oil.pdf

- South Africa’s Just Energy Transition Investment Plan (JET-IP): https://www.climatecommission.org.za/south-africas-jet-ip

- McKinsey & Company, 2022, Succeeding in the global offshore wind market https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/electric-power-and- natural-gas/our-insights/how-to-succeed-in-the-expanding-global- offshore-wind-market 23.

- Global Wind Energy Council, 2023, Global Wind Report 2023 https:// gwec.net/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/GWEC-2023_interactive.pdf 24.

Indonesia Energy Transition Outlook (IETO) 2023: https://iesr.or.id/ en/pustaka/indonesia-energy-transition-outlook-ieto-2023

EU energy strategy https://energy.ec.europa.eu/topics/energy- strategy_en

13. International Energy Agency, 2021, Net Zero by 2050: A Roadmap

for the Global Energy Sector https://www.iea.org/reports/net-zero- 25.

by-2050 Transformation https://climate-pact.europa.eu/system/

WWF, 2021, WWF Discussion Paper – Just Energy

- Rogers Williams University, The Nature Conservancy, The Marine

Affairs Institute, 2023, Can Offshore Wind Development Have a

Net Positive Impact on Biodiversity? Regulatory and Scientific 26. Perspectives and Considerations; The Bluedot Associates, 2023,

A guiding framework to support organisations to deliver net gains

for marine biodiversity https://bluedotassociates.com/a-guiding- framework-to-support-organisations-to-deliver-net-gains-for-marine- biodiversity/ - Science Based Targets Network, 2020, Science-based

Targets for Nature – Initial Guidance for Business https:// sciencebasedtargetsnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/SBTN- initial-guidance-for-business.pdf

files/2022-09/wwf_discussion_paper___just_energy_ transformation.pdf

WWF, 2022, Our Climate’s Secret Ally https://wwf.panda.org/ wwf_news/?6811966/climate-nature-secret-ally

- WWF, 2023, WWF Energy Vision – Clean Energy For People And Planet

- United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity, Target 15. Businesses assess and disclose biodiversity dependencies, impacts and risks, and reduce negative impacts https://www.cbd. int/gbf/targets/15/