Saving native bees over honey bees!

| Phoebe Weston in The Guardian Everyone wants to save the bees. Angelina Jolie put on a beekeeping suit for Guerlain and David Beckham proudly presented the King with a pot of honey from his bees in Oxfordshire. So many people wanting to do good have set up hives in their gardens or on roofs that they have become a symbol of sustainability. Of course, farming honeybees is a great way to make delicious honey, but there is a sting in the tail – keeping hives doesn’t help wild pollinators. Successful campaigns to “save the bees” have struck a chord with the public, but domestic honeybees don’t need saving because they are not in decline – setting up beehives is almost the equivalent of farming chickens to save wild birds. Meanwhile, there is a huge swathe of pollinators – about 270 species of solitary bee and 25 species of bumblebee – that are in real crisis and urgently need our help. Many of these threatened species are becoming rarer every year. |

setting up beehives is almost the equivalent of farming chickens to save wild birds

| Honeybees are essential for pollinating food crops (which we, obviously, need) but research suggests that when honeybee numbers boom, they negatively impact wild pollinators – especially in places where they are non-native such as Australia and America. High numbers of honeybees can actively harm wild bee populations because they outcompete them for nectar and pollen. They can forage further than other bees, but also there can be as many as 50,000 of them in a hive – far more than the nests that native bees live in. That’s not a problem when flowers are plentiful, but in environments where resources are limited, wild bees may struggle to find food. My reporting on this story this week led me to the work of Keng-Lou James Hung, an assistant professor of biology at the University of Oklahoma, who has been studying how this global bee battle is playing out on San Diego’s coastal scrub, where non-native honeybees have gone feral – living wild, not in a hive. Each spring, after the winter rains, this scrub landscape bursts into life. Sagebrush, white sage and buckwheat unfurl their leaves, throwing sweet aromas into the hot air. The landscape has all the hallmarks of a pristine ecosystem, but Hung’s research shows another story is unfolding here. Read more: |

| Wild bees visit different flowers to balance diet, study shows The best way to help bees? Don’t become a beekeeper like I did | Alison Benjamin I was terrified of bees – until the day 30,000 of them moved into my house | Pip Harry |

98% of bee biomass (the weight of all bees) in that area came from feral honeybees. They removed about 80% of pollen during the first day a flower opened

In July, he published a study finding that 98% of bee biomass (the weight of all bees) in that area came from feral honeybees. They removed about 80% of pollen during the first day a flower opened, according to the paper, published in the journal Insect Conservation and Diversity.“Context is king,” Hung told me. “As our study showed, in places like San Diego, it seems likelier that they are exploiting food resources to the detriment of native pollinators.

Species aren’t inherently “good” or “bad” but there are circumstances in which the introduction of species to certain locations could be problematic, just like goats and cats introduced to oceanic islands,” he added. Such high rates of pollen extraction leave little for the more than 700 species of native bees in the region, which need pollen to raise their offspring. Some of those species have not been seen for decades.

in places like San Diego, it seems likelier that they are exploiting food resources to the detriment of native pollinators

Scientists are finding this kind of story elsewhere in the world, including an experiment on an isolated Italian island showing that honeybees were causing declines in wild pollinators (you’ll have to read my piece to find out more about that). “As a researcher, I always get asked whether all the bees are in trouble, which at least means that people have recognised invertebrates as species that they should be concerned about, so that’s a good start,” says Hung.

For people who want to help all bees, the best way to do it is to plant a variety of flowers that bloom from early spring right through to late autumn. Many “weedy” plants are rich sources of pollen and nectar, so ditch weedkiller.

“We can’t blame the managed honeybee PR machine for being so good at its job; we just need to step up the game on native bee conservation advocacy and education,” he says. How people see the issue will influence how they take action, says Hung. “People who mistake honeybees as conservation targets would donate to causes that support honeybee health research and vote for policies that support beekeepers; if they had all the correct information, they might have instead chosen to allocate some significant portion of those commitments to native bee research and conservation instead.

”For people who want to help all bees, the best way to do it is to plant a variety of flowers that bloom from early spring right through to late autumn. Many “weedy” plants are rich sources of pollen and nectar, so ditch weedkiller. Leave areas undisturbed where solitary bees and bumblebees can nest. Also, be lazy! Mowing lawns less frequently can lead to an increase in bee abundance of up to 30%.

“I am quite encouraged that all over the world, there is an increased awareness of native bees; and more and more people now know that honeybees are not native to many parts of the world,” says Hung. “Overall I’m optimistic that people are more willing to accept nuanced answers and diversify their conservation interests.”

The island that banned hives: can honeybees actually harm nature?

On a tiny Italian island, scientists conducted a radical experiment to see if the bees were causing their wild cousins to decline

The age of extinction is supported by

The Guardian Thu 18 Sep 2025

Off the coast of Tuscany is a tiny island in the shape of a crescent moon. An hour from mainland Italy, Giannutri has just two beaches for boats to dock. In summer, hundreds of tourists flock there, hiking to the red and white lighthouse on its southern tip before diving into the clear waters. In winter, its population dwindles to 10. The island’s rocky ridges are coated with thickets of rosemary and juniper, and in warmer months the air is sweetened by flowers and the gentle hum of bees.

“Residents are people who like fishing, or being alone, or who have retired. Everyone has their story,” says Leonardo Dapporto, associate professor at the University of Florence.

It was Giannutri’s isolation that drew scientists here. They were seeking a unique open-air laboratory to answer a question that has long intrigued ecologists: could honeybees be causing their wild bee cousins to decline?

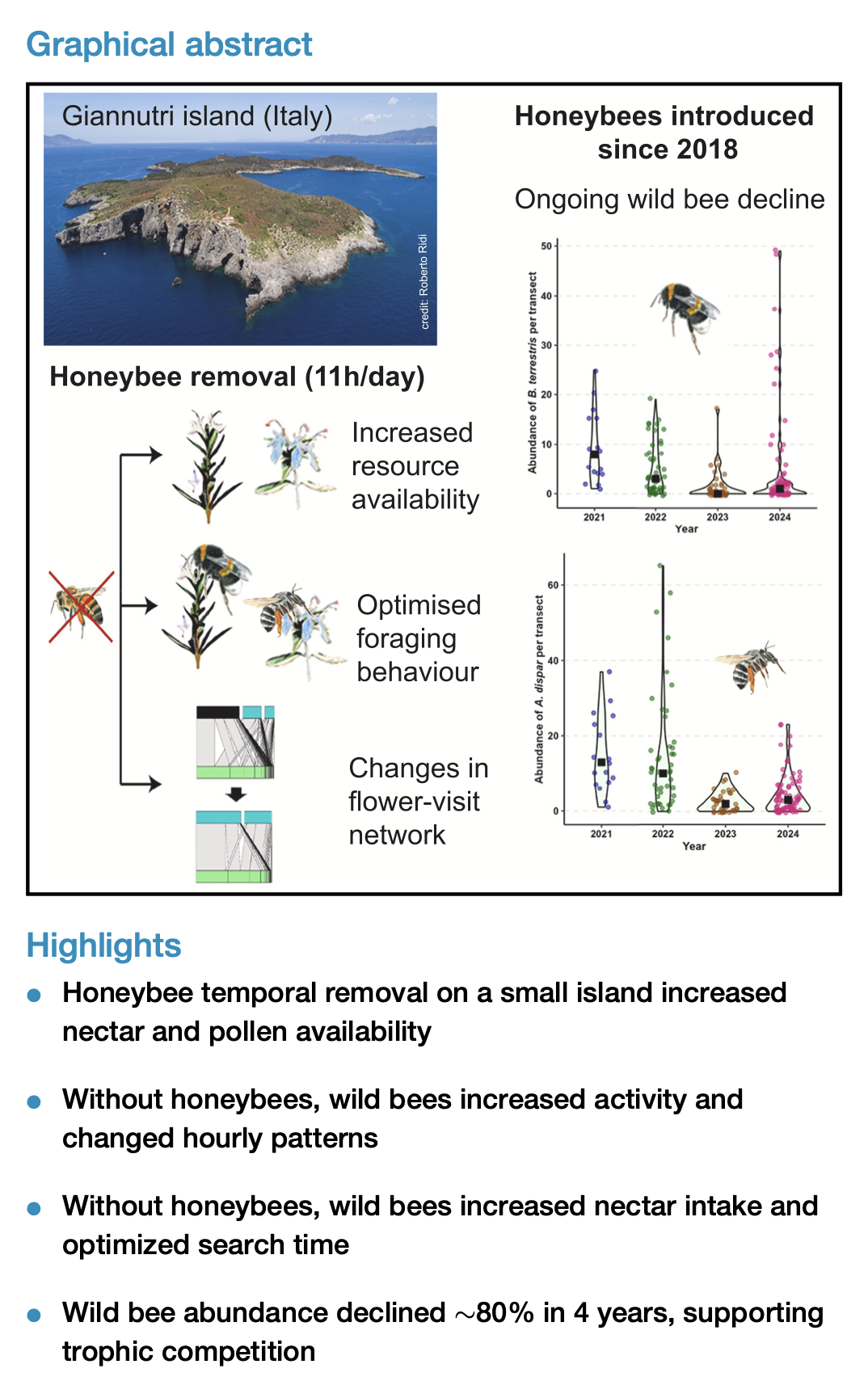

To answer this, they carried out a radical experiment. While Giannutri is too far from the mainland for honeybees to fly to it, 18 hives were set up on the island in 2018: a relatively contained, recently established population. Researchers got permission to shut the hives down, effectively removing most honeybees from the island.

When the study began, the island’s human population temporarily doubled in size, as teams of scientists fanned out across the scrubland tracking bees. Then came the ban: they closed hives on selected days during the peak foraging period, keeping the honeybees in their hives for 11 hours a day. Local people were sceptical. “For them, we were doing silly and useless things,” says Dapporto. But the results were compelling.

“‘Wow,’ was my first response,” says the lead researcher, Lorenzo Pasquali, from the University of Florence. When the data came together, “all the results were pointing in the same direction”.

The findings, published in Current Biology earlier this year, found that over the four years after the honeybees were introduced, populations of two vital wild pollinators – bumblebees and anthophora – fell by “an alarming” 80%. When the honeybees were locked up, there was 30% more pollen for other pollinators, and the wild bee species were sighted more frequently. Scientists observed that the wild species appeared to take their time pollinating flowers during the lockups, displaying different foraging behaviour. “The effect is visible,” says Dapporto.

Global bee battle

In terms of sheer abundance, the western honeybee (Apis mellifera) is the world’s most important single species of pollinator in wild ecosystems.

Originally native to Africa, the Middle East and southern Europe, honeybees have been shipped around the planet by humans to every continent except Antarctica. The battles playing out on this small Italian island are likely to be echoed in ecosystems everywhere.

While the number of honeybees is increasing (driven by commercial beekeeping) native pollinators are declining globally due to habitat loss, climate breakdown and use of chemicals in farming. But we are only beginning to understand how the great honeybee boom could also take a toll on wild pollinators.

In southern Spain, where honeybee numbers have more than tripled since the 1960s, research shows managed honeybees spilling into flower-rich woodlands after the orange crop has bloomed. The result: increased competition with wild pollinators.

During California’s annual almond bloom, about 90% of the US’s managed honeybees are recruited in to pollinate, with beekeepers trucking hives across the country to meet demand. “For this approximately month-long period, the impact of honeybees on native pollinators is likely huge,” says Dillon Travis from the University of California San Diego. During the off season – when honeybees are less in demand – beekeepers often keep them in wild ecosystems. “Native pollinators need to compete with millions of honeybees for limited food sources.”

If conditions are right, honeybees go feral and set up colonies in the wild. A 2018 study looking at the presence of honeybees in natural ecosystems found them in 89% of sites.

In California, feral honeybees are increasingly turning up in vast numbers in natural ecosystems hundreds of miles away from the almond fields.

Honeybee takeovers

Each spring, after the winter rains, San Diego’s coastal scrub landscape bursts into life. Sagebrush, white sage and buckwheat unfurl their leaves, throwing sweet aromas into the hot air. These sights and smells greeted graduate student Keng-Lou James Hung when he started studying this area of southern California in 2011, aged 22, after a well-regarded biologist told him it was one of the richest bee habitats on Earth.

The landscape has all the hallmarks of a pristine ecosystem: no tractor has tilled the land, no cattle grazed it; few humans tread here. “You can equate it to primary growth Amazonian rainforest in terms of how intact and undisturbed the ecosystem is,” says Hung.

It’s like a local grocery store trying to compete against Walmart. Once they’ve escaped there’s little we can do to stop honeybees

Keng-Lou James Hung

When Hung began his research, however, what he discovered flummoxed him. “I got to my field sites and all I was seeing were honeybees,” he remembers. “Imagine as an avid birder: you get to a pristine forest and all you are seeing are feral pigeons. That’s what was going on with me when I set foot in this habitat. It came as a shock.” Honeybees were everywhere – nesting in utility boxes, ground squirrel burrows and rock crevices.

In July, Hung – now an assistant professor at the University of Oklahoma – published a paper finding 98% of all bee biomass (ie, the weight of all bees) in that area were feral honeybees. They removed about 80% of pollen during the first day a flower opened, according to the paper, published in the journal Insect Conservation and Diversity.

Such high rates of pollen extraction leave little for the more than 700 species of native bees in the region, which need pollen to raise their offspring. Some of those species have not been seen for decades.

Hung believes honeybees’ social structure gives them the edge. Using the “hive mind”, they communicate the locations of plants and remove most of the pollen early in the morning before native bees begin searching for food. Most other bees operate as single agents, making decisions in isolation.

“It’s like a local grocery store trying to compete against Walmart,” says Hung. “Once they’ve escaped and established themselves there’s very little we can do to really stop honeybees. They’re very powerful and resilient creatures.”

In 1956, some experimental “Africanised” honeybees were accidentally released from a research apiary in São Paulo, Brazil, spreading out across south and Central America and into California. Their expansion has been described as one of the “most spectacular biological invasions of all time”.

Wider ecological effects

Habitat fragmentation, chemical use in farming and rising temperatures are key drivers of pollinator declines, but in areas such as in San Diego it is likely honeybees are also a significant contributing factor. “It is very difficult to imagine a scenario where a single species can remove four-fifths of all the pollen … without having too much of an impact on that ecosystem,” says Hung.

Not only is it bad for native wild bees, it can have effects throughout the ecosystem.

Studies have confirmed that plants in San Diego county are less healthy when pollinated by non-native honeybees. Potential impacts include fewer seeds germinating, and those that do may be smaller and produce fewer flowers. “This may create an ‘extinction vortex’,” says Travis, where less-healthy plants breed over generations until they can no longer survive. “I am unaware of any studies that determined that honeybees are beneficial where they are not native, excluding agricultural areas,” he says.

In some parts of Australia and America – where honeybees are not native – they can reach densities of up to 100 colonies per square kilometre. In regions such as Europe, where they are native, the picture is different.

There are about 75,000 free-living honeybee colonies across the UK, according to research last year, which was the first to quantify the density of these colonies. Based on these estimates, more than 20% of the UK’s honeybee population could be wild-living. “In Europe, the honeybee is a native species and low densities of wild-living colonies are natural components of many ecosystems,” says researcher Oliver Visick from the University of Sussex.

Visick has found densities of up to four wild-living colonies per square kilometre in historic deer parks in Sussex and Kent. “At these densities, wild-living colonies are unlikely to have a negative impact on other wild pollinators,” he says.

In ecosystems where honeybees are introduced, scientists say there should be more guidance on where large-scale beekeepers keep their hives after crops have bloomed to reduce their impact on native species. In other areas, such as islands, relocation or removal may be feasible.

The honeybee-free island

On Giannutri, when researchers told national park authorities their results they banned bee-keeping on the island.

The island, which is part of the Tuscan Archipelago national park, has been honeybee-free for more than a year and may now serve as a cautionary tale to other protected areas planning to introduce honeybees. Since the hives were removed, at least one of the species scientists have been monitoring appears to have slightly increased.

The story unfolding on this little Italian island and the scrublands of San Diego shows that honeybees may not be the universal environmental stewards we paint them to be, and challenges the popular view that they are the best way to save nosediving pollinator numbers. Unchecked, they can cast a long shadow over fragile ecosystems that some might believe they help preserve.

When the scientists returned to Giannutri, “It was a bit weird to go back to the island this year without the honeybees around. We were used to seeing them everywhere all over the island,” says Pasquali. “I was happy to observe the island in this new condition.”

Find more age of extinction coverage here, and follow the biodiversity reporters Phoebe Weston and Patrick Greenfield in the Guardian app for more nature coverage

Pasquali et al., 2025, Current Biology 35, 1576–1590. April 7, 2025 ª 2025 The Authors. Published by Elsevier Inc.