Collapse of the carbon offset lie: largest ever study proves carbon offsets don’t cut emissions.

Article summary below:

Romm, Joseph & Lezak, Stephen & Alshamsi, Amna. (2025). Are Carbon Offsets Fixable?. Annual Review of Environment and Resources. 50. 649-680. 10.1146/annurev-environ-112823-064813.

The Australia Institute edited offsets report 2023 below (under article)

Commentary: Kasper Benjamin Reimer Bjørkskov on LinkedIn

EXCLUSIVE — The verdict is in.

The most comprehensive review ever on carbon offsetting has just been published in the Annual Review of Environment and Resources.

And its message couldn’t be clearer:

👉 We must urgently phase out fake carbon offsets

👉 And cut emissions deeply and rapidly to reach near-zero by midcentury

Oxford calls it “the most comprehensive review of evidence on the effectiveness of carbon offsetting to date.”

https://lnkd.in/dVMcHgkQ

The Guardian calls it “a devastating blow to the idea that offsets can meaningfully cut emissions.”

After 25 years of data, the truth is undeniable:

“We must stop expecting carbon offsetting to work at scale. Almost everything up until this point has failed.” — Dr. Stephen Lezak, University of Oxford

These so-called “offsets” are meant to cancel out pollution — like paying to protect a forest, plant trees, or fund green projects while continuing to emit elsewhere.

But most don’t actually remove carbon from the atmosphere. They overpromise, underdeliver, and often collapse when forests burn, land use changes, or credits are double-counted.

In other words: they don’t erase emissions — they excuse them.

“These junk offsets are a dangerous distraction from the real solution: rapid and sustained emission cuts.” — Dr. Joseph Romm, Penn Center for Science, Sustainability and the Media

And the illusion goes beyond offsets.

The same false comfort underpins biomass energy and carbon storage in buildings — temporary tricks that make pollution look “neutral” while allowing industries to keep expanding.

This should be a turning point.

We can’t buy our way out of the crisis. We can’t burn or build our way to balance.

https://lnkd.in/dU9eZetD

The only honest path forward is to stop the harm at its source.

🔥 The science is clear. The moral path is, too.

Honesty — not offsets — is the new climate leadership.

What would it mean if we stopped pretending — and started transforming for real?

Carbon offsets have failed for 25 years, and most should be phased out – research

Smith School Oxford Estimated reading time: 2 Minutes

Academics at the University of Oxford and the University of Pennsylvania have conducted the most comprehensive review of evidence on the effectiveness on carbon offsetting to date and concluded the practice is ineffective and riddled with “intractable” problems.

Carbon offsets are projects that generate credits meant to represent the reduction, avoidance, or removal of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from the atmosphere. The first carbon offset was generated in 1989. The authors call for the phasing out of most credits except those generated by permanent carbon dioxide removal.

“We must stop expecting carbon offsetting to work at scale. We have assessed 25 years of evidence and almost everything up until this point has failed,” says co-author Dr Stephen Lezak, researcher at the Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment. “The present market failures are not due to a few bad apples but rather to systematic, deep-seated problems, which will not be resolved by incremental changes.”

“We hope our findings provide a moment of clarity ahead of COP30: These junk offsets—the ones not backed by permanent carbon removal and storage—are a dangerous distraction from the real solution to climate change, which is rapid and sustained emission reductions,” says lead author Dr Joseph Romm, Senior Research Fellow at the Penn Center for Science, Sustainability and the Media.

The most severe issues uncovered by the research are nonadditionality (generating credits without reducing emissions), impermanence, leakage, double counting, “perverse incentives,” and the “gameability” of crediting systems, where bad actors have been able to routinely circumvent even well-designed rules. Far from solving these problems, Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, which was finalised at COP29, simply restated “long-ignored tenets of carbon market development, with the specious expectation that this time the outcomes might differ significantly,” the authors say.

“Despite efforts to implement safeguards, carbon offset projects continue to face documented cases of weak accountability, risking the perpetuation of neocolonial patterns of appropriation. While nature-based projects can deliver local benefits, these should be financed through mechanisms other than carbon credits, such as contribution claims where projects are financed while still ensuring that purchasing entities are responsible for reducing their own emissions,” says co-author Amna Alshamsi, a doctoral researcher at the University of Sussex’s School of Global Studies. Previous research has shown how offset programs routinely overestimate their climate impact, in many cases by as much as a factor of ten or more.

Going forward, all offset markets should prioritise developing high-integrity, durable CDR and storage—with long-term measurement and verification—the authors conclude, while recognising that effective and scalable CDR may not be possible, and will certainly require intensive research and investment.

This approach aligns with the Oxford Offsetting Principles, which encourage companies to reduce emissions first and foremost, and to transition to durable, carbon removal offsetting for residual emissions.

Romm, Joseph & Lezak, Stephen & Alshamsi, Amna. (2025). Are Carbon Offsets Fixable?. Annual Review of Environment and Resources. 50. 649-680. 10.1146/annurev-environ-112823-064813.

ABSTRACT

This article provides a systematic review of the literature on carbon offsets. A growing number of studies have found that the most widely used offset programs continue to greatly overestimate their probable climate impact often by a factor of five to ten or more. Credit quality has remained a problem since the inception of carbon credits, despite repeated efforts to address the core challenges of additionality, leakage, double counting, environmental injustice, verification, and permanence. Combined, these issues have led many to conclude that overcrediting in carbon offsets is an intractable problem. These challenges helped stall the rapid growth in the voluntary carbon market (VCM) earlier this decade. They warrant renewed focus in the wake of COP29, where 200 nations significantly advanced the effort begun with the Paris Agreement to create the rules governing a global compliance market for carbon credits. But COP29 did not substantially address the quality problem, creating the risk the Paris compliance market will be rife with overcrediting and other problems—and that the VCM could undermine the Paris market. We recommend that all stakeholders begin focusing on high-integrity, durable carbon dioxide removal and storage, while recognizing that the recent literature has raised the question of whether durable means 100 years, 1,000 years, or longer. Ultimately, we find that many of the most popular offset project types feature intractable quality problems. We should focus on creating rules to find and fund the relatively few types of high-quality projects while employing alternative finance and strategies such as contribution claims for the critical projects in conservation, renewable energy, and sustainable development.Keywords

- carbon offsets,

- net zero,

- climate neutral,

- additionality,

- Paris Agreement,

- corresponding adjustment,

- mitigation contribution

SUMMARY POINTS

1. Carbon credits in both voluntary and compliance markets face seemingly intractable issues, leading to rampant overcrediting and undermining global climate progress.

2. The most severe issues are nonadditionality, impermanence, leakage, double counting, perverse incentives, and the gameability of crediting systems, where bad actors have been able to routinely circumvent even well-designed rules.

3. These intractable problems have persisted despite more than two decades of efforts at market reform and seem unlikely to be resolved in the foreseeable future by ongoing interventions by international and/or nonstate actors.

4. Irrespective of their climate impact, carbon credits demonstrate a pattern of major environmental justice violations. However, many projects are championed by local communities, Indigenous groups, and conservationists.

5. After nearly a decade of negotiations, COP29 launched the Paris Agreement’s global compliance markets for carbon credits, in the form of a bilateral pathway and a credit-based successor to the Clean Development Mechanism. But the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) did not substantially address quality problems, creating the risk the market will be rife with overcrediting and other shortcomings.

6. The voluntary carbon market could undermine the UNFCCC approaches. We recommend urgently phasing out non–CO2 removal (CDR) offsets over the next decade, especially if they lack a corresponding adjustment.

7. Going forward, all offset markets should prioritize developing high-integrity, durable CDR and storage, while recognizing that the recent literature has raised the question of whether durable means 100 years, 1,000 years, or longer.

8. Future research and investment is necessary to understand what role—and at what scale—CDR can play in helping meet global climate goals and limiting climate change.

References

- 1.Benton T, Calvo E, Cowie A, Masson-Delmotte V, Elbehri A, et al. 2022.. Annex I: glossary. . In Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the 6th Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, ed. PR Shukla, J Skea, R Slade, A Al Khourdajie, R van Diemen, et al . Cambridge University Press [Google Scholar]

- 2.Macintosh A, Butler D, Larraondo P, Evans MC, Ansell D, et al. 2024.. Australian human-induced native forest regeneration carbon offset projects have limited impact on changes in woody vegetation cover and carbon removals. . Commun. Earth Environ. 5:(1):149[Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cames M, Harthan RO, Füssler J, Lazarus M, Lee C, et al. 2016.. How additional is the Clean Development Mechanism? Study:, Öko-Institut [Google Scholar]

- 4.Probst BS, Toetzke M, Kontoleon A, Díaz Anadón L, Minx JC, et al. 2024.. Systematic assessment of the achieved emission reductions of carbon crediting projects. . Nat. Commun. 15::9562 [Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Badgley G, Freeman J, Hamman JJ, Haya B, Trugman AT, et al. 2022.. Systematic over-crediting in California’s forest carbon offsets program. . Glob. Change Biol. 28:(4):1433–45 [Crossref] [Web of Science] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haya B, Evans S, Brown L, Bukoski J, Butsic V, et al. 2023.. Comprehensive review of carbon quantification by improved forest management offset protocols. . Front. For. Glob. Change 6::958879 [Crossref] [Web of Science] [Google Scholar]

- 7.West TAP, Wunder S, Sills EO, Börner J, Rifai SW, et al. 2023.. Action needed to make carbon offsets from forest conservation work for climate change mitigation. . Science 381:(6660):873–77 [Crossref] [Citing articles] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pierce MH, Strong AL. 2023.. An evaluation of New York state livestock carbon offset projects under California’s Cap and Trade Program. . Carbon Manag. 14:(1):2211946 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pickering AJ, Arnold BF, Dentz HN, Colford JM, Null C. 2017.. Climate and health co-benefits in low-income countries: a case study of carbon financed water filters in Kenya and a call for independent monitoring. . Environ. Health Perspect. 125:(3):278–83 [Crossref][Medline] [Web of Science] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gill-Wiehl A, Kammen DM, Haya BK. 2024.. Pervasive over-crediting from cookstove offset methodologies. . Nat. Sustain. 7:(2):191–202 [Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kollmuss A, Schneider L, Zhezherin V. 2015.. Has joint implementation reduced GHG emissions? Lessons learned for the design of carbon market mechanisms. Work. Pap. , Stockholm Environment Institute [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shukla PR, Skea J, Slade R, Al Khourdajie A, van Diemen R, et al., eds. 2022.. Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the 6th Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press [Google Scholar]

- 13.United Nations High-Level Expert Group on the Net Zero Emissions Commitments of Non-State Entities. 2022.. Integrity matters: net zero commitments by businesses, financial institutions, cities and regions. Rep. , United Nations [Google Scholar]

- 14.Science Based Targets Initiative (SBTi). 2024.. Evidence synthesis report. Part 1: Carbon credits. Rep. , SBTi [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rathi A, White N, Pogkas D. 2024.. More companies ditch junk carbon offsets but new buyers loom. . Bloomberg, Oct. 24 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greenfield P. 2023.. Revealed: More than 90% of rainforest carbon offsets by biggest certifier are worthless, analysis shows. . The Guardian, Jan. 18 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Romm J. 2023.. Are carbon offsets unscalable, unjust, and unfixable—and a threat to the Paris Climate Agreement? White Paper, Penn Center for Science, Sustainability, and the Media, University of Pennsylvania [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elgin B. 2020.. These trees are not what they seem. . Bloomberg, Dec. 9 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baird IG, Green WN. 2020.. The Clean Development Mechanism and large dam development: contradictions associated with climate financing in Cambodia. . Clim. Change 161:(2):365–83 [Crossref] [Web of Science] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Calel R, Colmer J, Dechezleprêtre A, Glachant M. 2021.. Do carbon offsets offset carbon? Work. Pap. 398 , Grantham Research Institute for Climate Change and the Environment [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bennett G. 2022.. Today’s VCM, explained in three figures. . Ecosystem Marketplace. https://www.ecosystemmarketplace.com/articles/todays-vcm-explained-in-three-figures/ [Google Scholar]

- 22.United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). 2018.. Achievements of the Clean Development Mechanism, harnessing incentive for climate action (2001–2018). Rep. , United Nations [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen Q, Ryan N, Xu DY. 2024.. Adverse selection in carbon offset markets: evidence from the Clean Development Mechanism in China. Work. Pap. , Fudan University/Duke University/Yale University [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paulsson E. 2009.. A review of the CDM literature: from fine-tuning to critical scrutiny?. Int. Environ. Agreem. Political Law Econ. 9:(1):63–80 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haya B. 2010.. Carbon offsetting: an efficient way to reduce emissions or to avoid reducing emissions? An investigation and analysis of offsetting design and practice in India and China. PhD Thesis , University of California, Berkeley [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schneider L, Kollmuss A. 2015.. Perverse effects of carbon markets on HFC-23 and SF6 abatement projects in Russia. . Nat. Clim. Change 5:(12):1061–63 [Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- 27.World Bank. 2018.. Carbon Markets Under the Kyoto Protocol. World Bank [Google Scholar]

- 28.World Bank. 2023.. State and Trends of Carbon Pricing 2023. World Bank [Google Scholar]

- 29.California Air Resources Board (CARB). Compliance offset program. . CARB. https://ww2.arb.ca.gov/our-work/programs/compliance-offset-program [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haya B, Anderegg WRL, Axelsson K, Blanchard L, Lezak S. 2024.. Commentary on SBTi’s discussion paper: aligning corporate value chains to global climate goals. Comment, Berkeley Carbon Trading Project, University of California, Berkeley [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coffield SR, Vo CD, Wang JA, Badgley G, Goulden ML, et al. 2022.. Using remote sensing to quantify the additional climate benefits of California forest carbon offset projects. . Glob. Change Biol. 28:(22):6789–806 [Crossref] [Medline] [Web of Science] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stapp J, Nolte C, Potts M, Baumann M, Haya BK, Butsic V. 2023.. Little evidence of management change in California’s forest offset program. . Commun. Earth Environ. 4:(1):331 [Crossref] [Web of Science] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haya B. 2019.. The California Air Resources Board’s U.S. Forest offset protocol underestimates leakage. Response to Comments by the California Air Resources Board, Center for Environmental Public Policy, University of California, Berkeley [Google Scholar]

- 34.Randazzo NA, Gordon DR, Hamburg SP. 2023.. Improved assessment of baseline and additionality for forest carbon crediting. . Ecol. Appl. 33:(3):e2817 [Crossref] [Medline] [Web of Science] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Macintosh A, Larraondo P, Butler D, Ansell D, Waschka M, Evans M. 2022.. Trends in forest and sparse woody cover inside ERF HIR project areas relative to those in surrounding areas. Work. Pap., University of New South Wales [Google Scholar]

- 36.Allen M, Babiker M, Chen Y, de Coninck H, Connors S, et al. 2022.. Global Warming of 1.5°C: IPCC Special Report on Impacts of Global Warming of 1.5°C Above Pre-Industrial Levels in Context of Strengthening Response to Climate Change, Sustainable Development, and Efforts to Eradicate Poverty. Cambridge University Press [Google Scholar]

- 37.United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). 2016.. Decision 1/CP.21. . In Report of the Conference of the Parties on its 21st Session, Held in Paris from 30 November to 13 December 2015. Addendum. Part Two: Action Taken by the Conference of the Parties at Its 21st Session. United Nations. https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2015/cop21/eng/10a01.pdf#page=2 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schumer C. 2021.. How national net-zero targets stack up after the COP26 climate summit. Tech. Perspect. , World Resources Institute[Google Scholar]

- 39.Maizland L. COP26: here’s what countries pledged. Brief, Council on Foreign Relations [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bowcott H, Pacthod D, Pinner D. 2021.. What COP26 means for business. . McKinsey Sustainability, Novemb. 12 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Daedal Research. 2022.. Voluntary carbon market: analysis by traded volume, by credit retirements, by credit issuance, by project category, by type of project, by region size and trends with impact of COVID-19 and forecast up to 2027. Daedal Research. https://www.researchandmarkets.com/reports/5697812/voluntary-carbon-market-analysis-by-value-by [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shell Group, Boston Consulting Group (BCG). 2022.. The voluntary carbon market: 2022 insights and trends. Rep. , Shell Group/BCG[Google Scholar]

- 43.Trencher G, Nick S, Carlson J, Johnson M. 2024.. Demand for low-quality offsets by major companies undermines climate integrity of the voluntary carbon market. . Nat. Commun. 15::6863 [Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Haya B, Anderegg WRL, Axelsson K, Blanchard L, Lezak S. 2024.. Commentary on SBTi’s discussion paper: aligning corporate value chains to global climate goals. Comment, Berkeley Carbon Trading Project, University of California, Berkeley [Google Scholar]

- 45.Haya B, Alford-Jones K, Anderegg W, Beymer-Farris B, Blanchard L, et al. 2023.. Quality assessment of REDD+ carbon credit projects. Rep. , Berkeley Carbon Trading Project [Google Scholar]

- 46.International Energy Agency (IEA). 2024.. World energy outlook 2024. Rep. , IEA [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spalding-Fecher R, Achanta AN, Erickson P, Haites E, Lazarus M, et al. 2012.. Assessing the Impact of the Clean Development Mechanism. Rep. , High-Level Panel on the CDM Policy Dialogue [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schneider L. 2009.. Assessing the additionality of CDM projects: practical experiences and lessons learned. . Clim. Policy 9:(3):242–54[Crossref] [Web of Science] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Terrer C, Phillips RP, Hungate BA, Rosende J, Pett-Ridge J, et al. 2021.. A trade-off between plant and soil carbon storage under elevated CO2. . Nature 591:(7851):599–603 [Crossref] [Medline] [Web of Science] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Committee on Developing a Research Agenda for Carbon Dioxide Removal and Reliable Sequestration, Board on Atmospheric Sciences and Climate, Board on Energy and Environmental Systems, Board on Agriculture and Natural Resources, Board on Earth Sciences and Resources, et al. 2019.. Negative Emissions Technologies and Reliable Sequestration: A Research Agenda. National Academies Press[Google Scholar]

- 51.Kristensen JÅ, Barbero-Palacios L, Barrio IC, Jacobsen IBD, Kerby JT, et al. 2024.. Tree planting is no climate solution at northern high latitudes. . Nat. Geosci. 17:(11):1087–92 [Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gillenwater M, Broekhoff D, Trexler M, Hyman J, Fowler R. 2007.. Policing the voluntary carbon market. . Nat. Clim. Change 1:(711):85–87 [Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- 53.US Government Accountability Office (GAO). 2008.. International climate change programs: lessons learned from the European Union’s Emissions Trading Scheme and the Kyoto Protocol’s Clean Development Mechanism. Rep. GAO-09-151 , GAO [Google Scholar]

- 54.Guizar-Coutiño A, Jones JPG, Balmford A, Carmenta R, Coomes DA. 2022.. A global evaluation of the effectiveness of voluntary REDD+ projects at reducing deforestation and degradation in the moist tropics. . Conserv. Biol. 36:(6):e13970 [Crossref] [Medline] [Web of Science] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Song L, Temple J. 2021.. The climate solution actually adding millions of tons of CO2 into the atmosphere. . ProPublica/MIT Technology Review, April 29 [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wyburd I. 2024.. Hidden in plain sight: flawed renewable energy projects in the voluntary carbon market. Rep. , Carbon Market Watch[Google Scholar]

- 57.Civillini M, Lo J. 2024.. Renewable-energy carbon credits rejected by high-integrity scheme. . Climate Home News, Aug 7. https://www.climatechangenews.com/2024/08/07/renewable-energy-carbon-credits-rejected-by-high-integrity-scheme [Google Scholar]

- 58.White N, Ratcliffe V. 2022.. How the 2022 World Cup rebuilt a market for dodgy carbon credits. . Bloomberg, Novemb. 17 [Google Scholar]

- 59.Filewod B, McCarney G. 2023.. Avoiding carbon leakage from nature-based offsets by design. . One Earth 6:(7):790–802 [Crossref][Web of Science] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lamb WF, Gasser T, Roman-Cuesta RM, Grassi G, Gidden MJ, et al. 2024.. The carbon dioxide removal gap. . Nat. Clim. Change 14:(6):644–51 [Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Atmadja SS, Duchelle AE, De Sy V, Selviana V, Komalasari M, et al. 2022.. How do REDD+ projects contribute to the goals of the Paris Agreement?. Environ. Res. Lett. 17::044038 [Crossref] [Web of Science] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Haya B. 2019.. POLICY BRIEF: The California Air Resources Board’s U.S. Forest offset protocol underestimates leakage. Policy brief., Goldman School of Public Policy, UC Berkeley, May. https://gspp.berkeley.edu/assets/uploads/research/pdf/Policy_Brief-US_Forest_Projects-Leakage-Haya_2.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 63.Brown P, Cabarle B, Livernash ER. 1997.. Carbon counts estimating climate change mitigation in forestry projects. Rep., World Resources Institute [Google Scholar]

- 64.Richards K, Andersson K. 2001.. The leaky sink: persistent obstacles to a forest carbon sequestration program based on individual projects. . Clim. Policy 1:(1):41–54 [Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Archer D, Eby M, Brovkin V, Ridgwell A, Cao L, et al. 2009.. Atmospheric lifetime of fossil fuel carbon dioxide. . Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 37::117–34 [Crossref] [Web of Science] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Stubbs M, Hoover K, Ramseur JL. 2021.. Agriculture and forestry offsets in carbon markets: background and selected issues. Rep. , Congressional Research Service [Google Scholar]

- 67.Joppa L, Luers A, Willmott E, Friedmann SJ, Hamburg SP, Broze R. 2021.. Microsoft’s million-tonne CO2-removal purchase—lessons for net zero. . Nature 597:(7878):629–32 [Crossref] [Medline] [Web of Science] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Anderegg WRL, Chegwidden OS, Badgley G, Trugman AT, Cullenward D, et al. 2022.. Future climate risks from stress, insects and fire across US forests. . Ecol. Lett. 25:(6):1510–20 [Crossref] [Medline] [Web of Science] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Martin MP, Woodbury DJ, Doroski DA, Nagele E, Storace M, et al. 2021.. People plant trees for utility more often than for biodiversity or carbon. . Biol. Conserv. 261::109224 [Crossref] [Web of Science] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Axelsson K, Wagner A, Johnstone I, Allen M, Caldecott B, et al. 2024.. Oxford Principles for Net Zero Aligned Carbon Offsetting. Oxford Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment. Revis. ed. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Allen MR, Frame DJ, Friedlingstein P, Gillett NP, Grassi G, et al. 2024.. Geological net zero and the need for disaggregated accounting for carbon sinks. . Nature 638::343–50 [Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Brunner C, Hausfather Z, Knutti R. 2024.. Durability of carbon dioxide removal is critical for Paris climate goals. . Commun. Earth Environ. 5:(1):645 [Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Allen MR, Friedlingstein P, Girardin CAJ, Jenkins S, Malhi Y, et al. 2022.. Net zero: science, origins, and implications. . Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 47::849–87 [Crossref] [Citing articles] [Web of Science] [Google Scholar]

- 74.University of Oxford. 2024.. Redefining ‘net zero’ will not stop global warming, new study shows. . University of Oxford News, Novemb. 18 [Google Scholar]

- 75.Global CCS Institute. 2024.. Global status of CCS. Rep., Global CCS Institute [Google Scholar]

- 76.George JR. 2020.. Letter to Senator Robert Menendez, Inspector General for Tax Administration, Department of the Treasury, April 15 [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hoicka CE, Paterson M, Carter A, MacLean J, Eaton E, Homer-Dixon T. 2022.. Letter from scientists, academics, and energy system modellers: Prevent proposed CCUS investment tax credit from becoming a fossil fuel subsidy. Open Letter, Environmental Defense [Google Scholar]

- 78.García JH, Torvanger A. 2019.. Carbon leakage from geological storage sites: implications for carbon trading. . Energy Policy 127::320–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2018.11.015 [Crossref] [Web of Science] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Romm J. 2025.. The Hype About Hydrogen: False Promises and Real Solutions in the Race to Save the Climate. Island Press [Google Scholar]

- 80.Monastersky R. 2013.. Seabed scars raise questions over carbon-storage plan. . Nature 504:(7480):339–40 [Crossref] [Medline] [Web of Science] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Donnelly E. 2024.. Norway’s Equinor admits it over-reported amount of carbon captured at flagship project for years. . DeSmog, Oct. 28 [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ringrose PS, Mathieson AS, Wright IW, Selama F, Hansen O, et al. 2013.. The In Salah CO2 storage project: lessons learned and knowledge transfer. . Energy Proc. 37::6226–36 [Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Johnson AM Jr. 2008.. An economic analysis of the duty to disclose information: lessons learned from the caveat emptor doctrine. . San Diego Law Rev. 45:(1):79–132 [Google Scholar]

- 84.Smith JB. 2019.. California compliance offsets: problematic protocols and buyer behavior. Work. Pap. 120 , Mossavar-Rahmani Center for Business and Government, Harvard Kennedy School [Google Scholar]

- 85.Cloutier D, Robinson S, Sullivan G. 2021.. The coming U.S. regulatory oversight of, and demand for, climate disclosure. . CRE Real Estate Issues 45:(28). https://cre.org/real-estate-issues/the-coming-u-s-regulatory-oversight-of-and-demand-for-climate-disclosure[Google Scholar]

- 86.Broekhof D, Gillenwater M, Colbert-Sangree T, Cage P. 2020.. Securing climate benefit: a guide to using carbon offsets. Rep. , Greenhouse Gas Management Institute/Stockholm Environment Institute. https://www.offsetguide.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Carbon-Offset-Guide_3122020.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 87.Stavins RN. 1997.. Policy instruments for climate change: How can national governments address a global problem?. Univ. Chicago Leg. Forum 1997::293–329 [Google Scholar]

- 88.Victor DG. 2010.. The politics and economics of international carbon offsets. . In Modeling the Economics of Greenhouse Gas Mitigation: Summary of a Workshop. National Academies Press [Google Scholar]

- 89.Coy P. 2023.. To fight climate change, we need a better carbon market. . New York Times, Aug. 23 [Google Scholar]

- 90.Dutu R, Nosal E, Rocheteau G. 2005.. The tale of Gresham’s law. Econ. Comment., Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland [Google Scholar]

- 91.Watanabe K, Saunders J, Turner G, Nishikawa L. 2024.. Corporate emissions performance and the use of carbon credit. Res. Rep., MSCI [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ecosystem Marketplace Insights Team. 2023.. New research: Carbon credits are associated with businesses decarbonizing faster. Ecosystem Marketplace [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sylvera. 2023.. Carbon credits: permission to pollute, or pivotal for progress? Mark. Anal. Rep., Sylvera [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ecosystem Marketplace. 2023.. State of the voluntary carbon markets 2023. Rep., Forest Trends Association [Google Scholar]

- 95.Trouwloon D, Streck C, Chagas T, Martinus G. 2023.. Understanding the use of carbon credits by companies: a review of the defining elements of corporate climate claims. . Glob. Chall. 7:(4):2200158 [Crossref] [Medline] [Web of Science] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Stolz N, Probst B. 2024.. The negligible role of carbon offsetting in corporate climate strategies. Work. Pap. , Max Planck Institute for Innovation and Competition [Google Scholar]

- 97.Dufrasne G. 2023.. Correlation or causation: Is there a link between carbon offsetting and climate ambition?. Carbon Market Watch, Dec. 2 [Google Scholar]

- 98.Elgin B, Rangarajan S. 2022.. What really happens when emissions vanish. . Bloomberg, Oct. 31 [Google Scholar]

- 99.Gillenwater M. 2008.. Redefining RECs. Part 1: Untangling attributes and offsets. . Energy Policy 36:(6):2109–19 [Crossref] [Web of Science] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Bjørn A, Lloyd S, Brander M, Matthews H. 2022.. Renewable energy certificates threaten the integrity of corporate science-based targets. . Nat. Clim. Change 12:(6):539–46 [Crossref] [Web of Science] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Guix M, Ollé C, Font X. 2022.. Trustworthy or misleading communication of voluntary carbon offsets in the aviation industry. . Tour. Manag. 88::104430 [Crossref] [Web of Science] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Competition and Markets Authority. 2021.. Global sweep finds 40% of firms’ green claims could be misleading. Press Release, UK Government, Jan. 28 [Google Scholar]

- 103.Trencher G, Blondeel M, Asuka J. 2023.. Do all roads lead to Paris? Comparing pathways to net-zero by BP, Shell, Chevron and ExxonMobil. . Clim. Change 176:(7):83 [Crossref] [Web of Science] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Watson E, Massei M, Farrelly A, Castro E, Ernest-Jones H. 2024.. SBTi Corporate Net-Zero Standard, version 1.2. Standard, Science Based Targets Initiative [Google Scholar]

- 105.Environmental Defense Fund. 2018.. How to avoid double counting of emissions reductions. Handbook, Environmental Defense Fund[Google Scholar]

- 106.Schneider L, Duan M, Stavins R, Kizzier K, Broekhoff D, et al. 2019.. Double counting and the Paris Agreement rulebook. . Science 366:(6462):180–83 [Crossref] [Medline] [Web of Science] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Favasuli S. 2021.. Paris accord Article 6 approval set to jump-start evolution of voluntary carbon market. . S&P Global Commodity Insights, Novemb. 17 [Google Scholar]

- 108.United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). 2023.. Overview of Article 6.4: the mechanism. Webinar Slides, United Nations Climate Change Regional Collaboration Centres [Google Scholar]

- 109.Gold Standard for the Global Goals. 2022.. Claims guidelines. Guidel., Gold Standard Foundation [Google Scholar]

- 110.Kreibich N, Hermwille L. 2021.. Caught in between: credibility and feasibility of the voluntary carbon market post-2020. . Clim. Policy21:(7):939–57 [Crossref] [Web of Science] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Grubb M, Vrolijk C, Brack D. 2018.. Kyoto Protocol 1999: A Guide and Assessment. Routledge [Google Scholar]

- 112.Choudhury SR. 2021.. Shades of REDD+: corresponding adjustments, equity, and climate justice. Rep., Ecosystem Marketplace[Google Scholar]

- 113.Schneider L, Kollmuss A, Lazarus M. 2014.. Addressing the risk of double counting emission reductions under the UNFCCC. Work. Pap. 2014-02 , Stockholm Environment Institute [Google Scholar]

- 114.Moura Costa P. 2022.. Opinion: corresponding adjustments and their impact on NDCs and additionality. Rep., Ecosystem Marketplace[Google Scholar]

- 115.The World Bank. 2023.. Corresponding Adjustment and Pricing of Mitigation Outcomes. World Bank Working Paper [Google Scholar]

- 116.Porsborg-Smith A, Nielsen J, Owolabi B, Clayton C. 2023.. Why the voluntary carbon market is thriving. Rep. , Boston Consulting Group [Google Scholar]

- 117.Padin-Dujon A. 2024.. COP29: Correspondingly adjusted carbon credits trading at $7–22, says market analytics firm. . Carbon Pulse, Novemb. 20 [Google Scholar]

- 118.Streck C, Bouchon S, Rocha M, Trouwloon D, Dyck M. 2023.. Double claiming and corresponding adjustments. Rep., Climate Focus[Google Scholar]

- 119.International Carbon Reduction and Offset Alliance (ICROA). 2020.. ICROA’s position on scaling private sector voluntary action post-2020. Rep. , ICROA [Google Scholar]

- 120.Brander M, Broekhoff D, Hewlett O. 2022.. The future of the voluntary offset market: the need for corresponding adjustments. Work. Pap. , University of Edinburgh [Google Scholar]

- 121.Gold Standard Foundation. 2020.. Operationalising and scaling post-2020 voluntary carbon market. Tech. Rep. , Gold Standard Foundation [Google Scholar]

- 122.UN-REDD Programme. Cancun safeguards. UN-REDD Programme. https://www.un-redd.org/glossary/cancun-safeguards

- 123.Olsen KH, Fenhann J. 2008.. Sustainable development benefits of clean development mechanism projects. . Energy Policy 36:(8):2819–30 [Crossref] [Web of Science] [Google Scholar]

- 124.World Bank. 2021.. State and Trends of Carbon Pricing 2021. World Bank [Google Scholar]

- 125.Sills EO, Atmadja S, de Sassi C, Duchelle AE, Kweka D, et al., eds. 2014.. REDD+ on the ground: a case book of subnational initiatives across the globe. Rep., Center for International Forestry [Google Scholar]

- 126.Imai N, Samejima H, Langner A, Ong RC, Kita S, et al. 2009.. Co-benefits of sustainable forest management in biodiversity conservation and carbon sequestration. . PLOS ONE 4:(12):e8267 [Crossref] [Medline] [Web of Science] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Rahman MM, Zimmer M, Ahmed I, Donato D, Kanzaki M, Xu M. 2021.. Co-benefits of protecting mangroves for biodiversity conservation and carbon storage. . Nat. Commun. 12::3875 [Crossref] [Medline] [Web of Science] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Alusiola RA, Schilling J, Klär P. 2021.. REDD+ conflict: understanding the pathways between forest projects and social conflict. . Forests 12:(6):748 [Crossref] [Web of Science] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Duker AEC, Tadesse TM, Soentoro T, De Fraiture C, Kemerink-Seyoum JS. 2019.. The implications of ignoring smallholder agriculture in climate-financed forestry projects: empirical evidence from two REDD+ pilot projects. . Clim. Policy 19:(Suppl. 1):S36–46 [Crossref] [Web of Science] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Milne S, Mahanty S. 2019.. Value and bureaucratic violence in the green economy. . Geoforum 98::133–43 [Crossref] [Web of Science][Google Scholar]

- 131.Milne S, Mahanty S, To P, Dressler W, Kanowski P, Thavat M. 2019.. Learning from “actually existing” REDD+: a synthesis of ethnographic findings. . Conserv. Soc. 17:(1):84 [Crossref] [Citing articles] [Web of Science] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Lachnitt J, Tilianaki M. 2023.. Carbon offsetting at the cost of human rights? The case of TotalEnergies’ BaCaSi project in Congo. Rep., Secours Catholique, Caritas [Google Scholar]

- 133.Counsell S. 2023.. Blood carbon: how a carbon offset scheme makes millions from Indigenous land in Northern Kenya. Rep., Survival International [Google Scholar]

- 134.Battocletti V, Enriques L, Romano A. 2024.. The voluntary carbon market: market failures and policy implications. . Univ. Colo. Law Rev. 95:(3):519–78 [Google Scholar]

- 135.Sawathvong S, Hyakumura K. 2024.. A comparison of the free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC) guidelines and the “Implementation of Governance, Forest Landscapes, and Livelihoods” project in Lao PDR: the FPIC team composition and the implementation process. . Land 13:(4):408 [Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Haya B, Parekh P. 2011.. Hydropower in the CDM: examining additionality and criteria for sustainability. Work. Pap. , University of California, Berkeley [Google Scholar]

- 137.Fearnside PM. 2013.. Credit for climate mitigation by Amazonian dams: loopholes and impacts illustrated by Brazil’s Jirau Hydroelectric Project. . Carbon Manag. 4:(6):681–96 [Google Scholar]

- 138.Fearnside PM. 2015.. Tropical hydropower in the clean development mechanism: Brazil’s Santo Antônio Dam as an example of the need for change. . Clim. Change 131:(4):575–89 [Crossref] [Web of Science] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Hultman N, Lou J, Hutton S. 2020.. A review of community co-benefits of the clean development mechanism (CDM). . Environ. Res. Lett. 15::053002 [Crossref] [Web of Science] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Angelsen A, Jagger P, Babigumira R, Belcher B, Hogarth NJ, et al. 2014.. Environmental income and rural livelihoods: a global-comparative analysis. . World Dev. 64:(Suppl.):12–28 [Crossref] [Medline] [Web of Science] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Chomba S, Kariuki J, Lund JF, Sinclair F. 2016.. Roots of inequity: how the implementation of REDD+ reinforces past injustices. . Land Use Policy 50::202–13 [Crossref] [Citing articles] [Web of Science] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Hengeveld M. 2023.. Carbon offsetting project and human rights abuse in Kenya. Rep., SOMO [Google Scholar]

- 143.Scheba A, Rakotonarivo OS. 2016.. Territorialising REDD+: conflicts over market-based forest conservation in Lindi. , Tanzania. Land Use Policy 57::625–37 [Crossref] [Web of Science] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Human Rights Watch. 2019.. Carbon credits or land grabs? A case study of the Rimba Raya REDD+ project in Central Kalimantan, Indonesia. Rep., Human Rights Watch [Google Scholar]

- 145.Poudyal M, Ramamonjisoa BS, Hockley N, Rakotonarivo OS, Gibbons JM, et al. 2016.. Can REDD+ social safeguards reach the ‘right’ people? Lessons from Madagascar. . Glob. Environ. Change 37::31–42 [Crossref] [Web of Science] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Benjaminsen G. 2014.. Between resistance and consent: project–village relationships when introducing REDD+ in Zanzibar. . Forum Dev. Stud. 41:(3):377–98 [Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Mickels-Kokwe G, Mangwanya L. 2015.. Carbon Conflicts and Forest Landscapes in Africa. London:: Routledge [Google Scholar]

- 148.Yeang D. Community tenure rights and REDD+: a review of the Oddar Meanchey Community Forestry REDD+ project in Cambodia. . Aust. J. South-East Asian Stud. 5:(2):263–74 [Google Scholar]

- 149.Chávez LT. 2024.. Carbon offsetting’s casualties. Rep., Human Rights Watch [Google Scholar]

- 150.Oakland Institute. 2019.. Evicted for carbon credits: Norway, Sweden, and Finland displace Ugandan farmers for carbon trading. Rep., Oakland Institute. https://www.oaklandinstitute.org/sites/oaklandinstitute.org/files/evicted-carbon_0.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 151.Lane R, Newell P. 2016.. The political economy of carbon markets. . In The Palgrave Handbook of the International Political Economy of Energy, ed. T Van De Graaf, BK Sovacool, A Ghosh, F Kern, MT Klare . Palgrave Macmillan [Google Scholar]

- 152.Kansanga MM, Luginaah I. 2019.. Agrarian livelihoods under siege: carbon forestry, tenure constraints and the rise of capitalist forest enclosures in Ghana. . World Dev. 113::131–42 [Crossref] [Web of Science] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Boyle L. 2021.. Carbon offsetting ‘a new form of colonialism,’ says Indigenous leader at COP26. . The Independent, Novemb. 4 [Google Scholar]

- 154.Pham L, Gilbertson T, Witchger J, Soto-Danseco E, Goldtooth TBK. 2022.. Nature-based solutions. Clim. Justice Prog. Brief., Indigenous Environmental Network [Google Scholar]

- 155.Middleton Manning BR, Reed K. 2019.. Returning the Yurok Forest to the Yurok Tribe: California’s first tribal carbon credit project. . Stanford Environ. Law J. 39:(39):71–124 [Google Scholar]

- 156.Schmid DV. 2023.. Are forest carbon projects in Africa green but mean? A mixed-method analysis. . Clim. Dev. 15:(1):45–59 [Crossref][Web of Science] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Docena H, ed. 2010.. Costly dirty money-making schemes: the Clean Development Mechanism projects in the Philippines. Rep., Focus on the Global South [Google Scholar]

- 158.Lee CM, Lazarus M, Smith GR, Todd K, Weitz M. 2013.. A ton is not always a ton: a road-test of landfill, manure, and afforestation/reforestation offset protocols in the U.S. carbon market. . Environ. Sci. Policy 33::53–62 [Crossref] [Web of Science] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Verra. 2017.. VCS version 3 rules and requirements. Verra. https://verra.org/programs/verified-carbon-standard/vcs-version-3-archive-rules-and-requirements/ [Google Scholar]

- 160.Verra. 2024.. VCS Standard, Version 4.7. Verra, April 15. https://verra.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/VCS-Standard-v4.7-FINAL-4.15.24.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 161.European Commission. 2023.. Technical guidance on the application of “do no significant harm” under the EU taxonomy regulation. Recovery and Resilience Facility, European Commission. 2023 O.J. ( C 111) 33 [Google Scholar]

- 162.Dev T. 2023.. Discredited: the voluntary carbon market in India. Rep., Centre for Science and Environment India [Google Scholar]

- 163.McConnell C, Maina N, Woolfrey S. 2024.. Carbon offset deals and the risks of green grabbing. Rep., International Institute for Sustainable Development [Google Scholar]

- 164.Partnership for Market Readiness. 2021.. A Guide to Developing Domestic Carbon Crediting Mechanisms. World Bank [Google Scholar]

- 165.Chomba S, Kariuki J, Lund JF, Sinclair F. 2016.. Roots of inequity: how the implementation of REDD+ reinforces past injustices. . Land Use Policy 50::202–13 [Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Luttrell C, Sills E, Aryani R, Ekaputri AD, Evinke MF. 2018.. Beyond opportunity costs: Who bears the implementation costs of reducing emissions from deforestation and degradation?. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Change 23:(2):291–310 [Crossref] [Medline] [Web of Science][Google Scholar]

- 167.Lyons K, Westoby P. 2014.. Carbon colonialism and the new land grab: plantation forestry in Uganda and its livelihood impacts. . J. Rural Stud. 36::13–21 [Crossref] [Citing articles] [Web of Science] [Google Scholar]

- 168.da Silva CA, dos Santos SC, Rossetto OC. 2024.. The Paiter Suruí Indigenous people in defence of their territory: the case of the Suruí Forest Carbon Project (PCFS)—Rondonia/Brazil. . In Traditional Knowledge and Climate Change, ed. A Penteado, SP Chakrabarty, OH Shaikh . Springer [Google Scholar]

- 169.Brown HC. 2024.. Forest-preservation credits win seal of approval from industry watchdog. . Wall Street Journal, Novemb. 20 [Google Scholar]

- 170.Mundy S. 2024.. Solving the carbon market ‘integrity crisis. .’ Financial Times, Aug. 7 [Google Scholar]

- 171.Integrity Council for the Voluntary Carbon Market (ICVCM). 2024.. ICVCM annual review 2023–2024: building integrity in carbon markets. Annu. Rep., ICVCM [Google Scholar]

- 172.Forest Trends Association. 2024.. State of the voluntary carbon market 2024. Rep., Ecosystem Marketplace [Google Scholar]

- 173.West TAP, Börner J, Sills EO, Kontoleon A. 2020.. Overstated carbon emission reductions from voluntary REDD+ projects in the Brazilian Amazon. . PNAS 117:(39):24188–94 [Crossref] [Medline] [Web of Science] [Google Scholar]

- 174.Elgin B. 2023.. Carbon offsets undercut California’s climate progress, researchers find. . Bloomberg, Sept. 21 [Google Scholar]

- 175.Greenfield P. 2024.. Cookstove carbon offsets overstate climate benefit by 1,000%, study finds. . The Guardian, Jan. 23 [Google Scholar]

- 176.Pontecorvo E. 2024.. Clean cookstoves are kind of bogus, too. . Heatmap, Jan. 23 [Google Scholar]

- 177.Blake H. 2023.. The great cash-for-carbon hustle. . New Yorker, Oct. 16 [Google Scholar]

- 178.Parker B. 2023.. Carbon offsetting schemes are ‘fraud’, says major airline CEO. . The Independent, July 26 [Google Scholar]

- 179.Greenfield P. 2023.. Delta Air Lines faces lawsuit over $1bn carbon neutrality claim. . The Guardian, May 30. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2023/may/30/delta-air-lines-lawsuit-carbon-neutrality-aoe [Google Scholar]

- 180.Rathi A, White N, Pogkas D. 2024.. More companies ditch junk carbon offsets but new buyers loom. . Bloomberg, Oct. 24 [Google Scholar]

- 181.Ødegård C. 2024.. Governing the voluntary carbon market. Master’s Thesis , University of Oslo [Google Scholar]

- 182.White N. 2024.. Resignations at carbon oversight body raise quality questions. . Bloomberg, Dec. 10 [Google Scholar]

- 183.West TAP, Wunder S, Sills EO, Börner J, Rifai SW, et al. 2023.. Action needed to make carbon offsets from forest conservation work for climate change mitigation. . Science 381:(6660):873–77 [Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- 184.Blanchard L, Haya B, Lezak S, Anderegg W. 2024.. The history of “contribution” approaches for climate mitigation: a narrative review. . SSRN Scholarly Pap. 4971756. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4971756

- 185.Dufrasne G. 2020.. Above and beyond carbon offsetting: alternatives to compensation for climate action and sustainable development. Policy brief., Carbon Market Watch. https://carbonmarketwatch.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/AboveAndBeyondCarbonOffsetting.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 186.Kreibich N, Fraling J, Schulze-Steinen M, Kühlert M. 2024.. A guide to implementing the contribution claim model. Foundation Development and Climate Alliance. https://allianz-entwicklung-klima.de/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/2409_Guide_Contribution-Claim-Model.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 187.Fearnehough H, Skribbe R, de Grandpré J, Day T, Warnecki C. 2023.. A guide to climate contributions. Rep., New Climate Institute[Google Scholar]

- 188.UNFCCC Article 6.4 Supervisory Body. Application of the requirements of Chapter V.B (Methodologies) for the development and assessment of Article 6.4 mechanism methodologies (v.01.1). Standard, UNFCCC [Google Scholar]

- 189.United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). 2024.. Guidance on cooperative approaches referred to in Article 6, paragraph 2, of the Paris Agreement and in decision 2/CMA.3. UNFCCC. https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/cma3_auv_12a_PA_6.2.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 190.Fransen T, Henderson C, O’Connor R, Alayza N, Caldwell M, et al. 2022.. The state of nationally determined contributions: 2022. Rep., World Resources Institute [Google Scholar]

- 191.Romm J. 2023.. Why direct air carbon capture and storage (DACCS) is not scalable and ‘net zero’ is a dangerous myth. White Paper, Penn Center for Science, Sustainability, and the Media, University of Pennsylvania [Google Scholar]

- 192.Fankhauser S, Smith SM, Allen M, Axelsson K, Hale T, et al. 2022.. The meaning of net zero and how to get it right. . Nat. Clim. Change12:(1):15–21 [Crossref] [Web of Science] [Google Scholar]

- 193.Pathak M, Slade R, Pichs-Madruga R, Ürge-Vorsatz D, Shukla PR, et al. 2023.. Technical summary. . In Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the 6th Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, ed. PR Shukla, J Skea, R Slade, A Al Khourdajie, R van Diemen, et al . Cambridge University Press [Google Scholar]

- 194.Mac Dowell N, Fennell PS, Shah N, Maitland GC. 2017.. The role of CO2 capture and utilization in mitigating climate change. . Nat. Clim. Change 7:(4):243–49 [Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- 195.Smith S, Geden O, Gidden M, Lamb W, Nemet G, et al., eds. 2024.. The State of Carbon Dioxide Removal—2nd Edition. Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment, University of Oxford. [Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- 196.Carton W, Asiyanbi A, Beck S, Buck HJ, Lund JF. 2020.. Negative emissions and the long history of carbon removal. . Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 11:(6):e671 [Crossref] [Web of Science] [Google Scholar]

- 197.Ho DT. 2023.. Carbon dioxide removal is not a current climate solution—we need to change the narrative. . Nature 616:(7955):9[Crossref] [Medline] [Web of Science] [Google Scholar]

- 198.EnergyAustralia. 2025.. Go Neutral Litigation – EnergyAustralia acknowledges issues with “offsetting” and moves away from carbon offsets for its residential customer products. News Release, May 19, https://www.energyaustralia.com.au/about-us/media/news/go-neutral-litigation-energyaustralia-acknowledges-issues-offsetting-and-moves [Google Scholar]

- 199.Drucker PF. 1963.. Managing for business effectiveness. . Harvard Bus. Rev. 41:(3):53–60 [Google Scholar]

- 200.European Academies’ Science Advisory Council (EASAC). 2022.. Forest bioenergy update: BECCS and its role in integrated assessment models. Rep., EASAC [Google Scholar]

- 201.Romm J. 2023.. Why scaling bioenergy and bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS) is impractical and would speed up global warming. White Paper, Penn Center for Science, Sustainability, and the Media, University of Pennsylvania [Google Scholar]

- 202.McQueen N, Desmond MJ, Socolow RH, Psarras P, Wilcox J. 2021.. Natural gas versus electricity for solvent-based direct air capture. . Front. Clim. 2::618644 [Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- 203.Lattner J, Stevenson S. 2021.. Renewable power for carbon dioxide mitigation. . AIChE J. 2021:(3):51–58 [Google Scholar]

- 204.Kahsar R, Bloch C, Newcomb J, Wohl G. 2022.. Direct air capture and the energy transition. Strategic Insight, RMI, July 18. https://rmi.org/direct-air-capture-and-the-energy-transition/ [Google Scholar]

The Australia Institute Carbon Offset report 2023: Here are 22 Times Carbon Offsets Were Found to be Dodgy

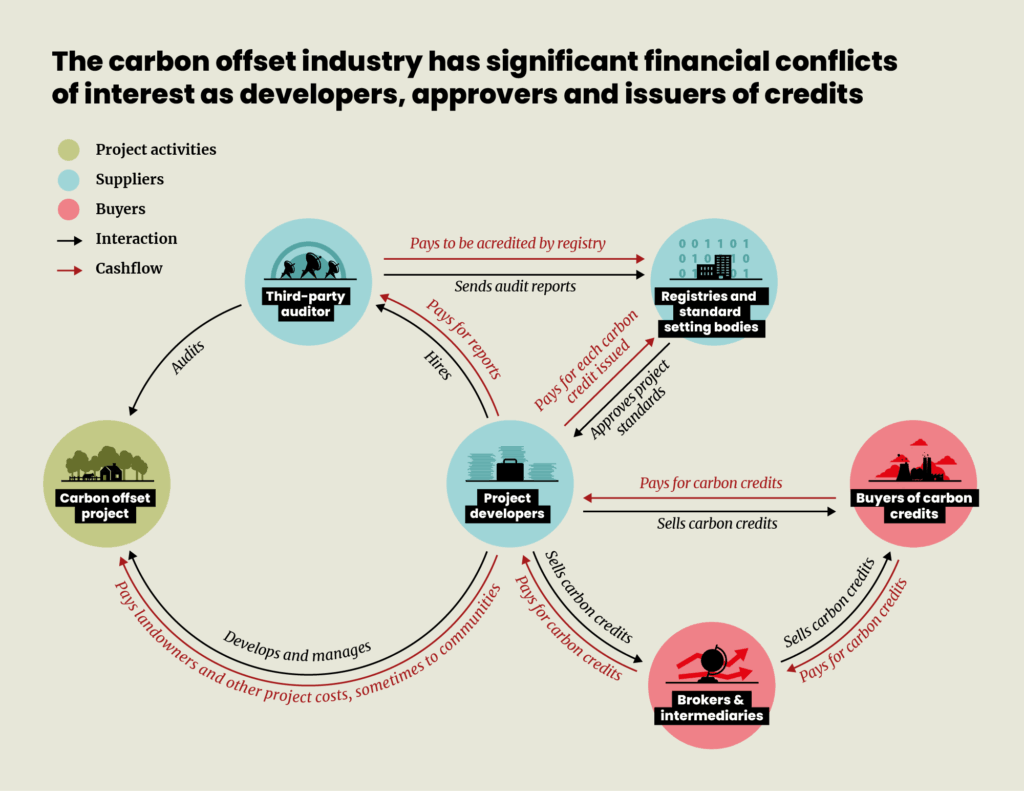

Carbon offsetting has received a lot of attention recently. As businesses and governments look to meet their climate targets, many are turning to carbon offsets. That is, they are paying someone else to reduce or avoid putting greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, so they don’t have to.

Yet, study after study, and report after report, exposes serious integrity issues with carbon offsets – both here in Australia and globally. Carbon offsets are issued and deployed at an array of scales, around the world – sometimes voluntarily, sometimes to meet obligations under regulations. Across these various forms of carbon offsets, the thing that seems to be common are questions over their quality.

Here we bring together a list of just some of the many studies and independent investigations that, collectively, highlight the general lack of integrity of carbon offsets. Across the various locations and methodologies surveyed here, all raise serious questions about continued reliance on carbon offsets to meet climate mitigation goals.

As these studies show, depending on carbon offsets to avoid dangerous climate change is fatally flawed. Offsets are deployed to justify continued emissions, just as we need to be directly scaling down our use of fossil fuels.

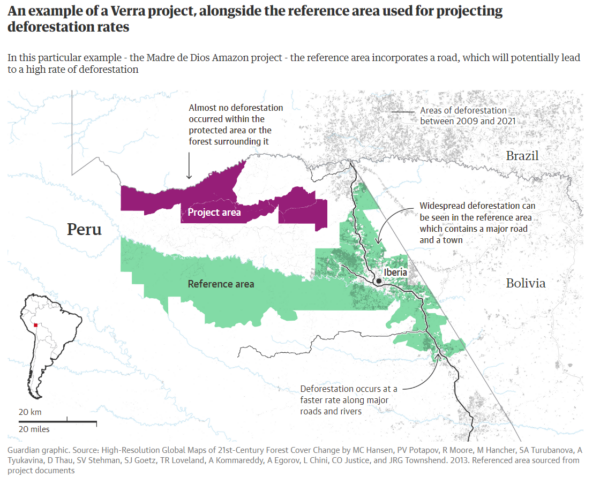

1/ The Guardian (and others) found that 90% of rainforest carbon offsets are worthless.

Revealed: more than 90% of rainforest carbon offsets by biggest certifier are worthless, analysis shows, Patrick Greenfield, The Guardian, 2023.

Key Finding: This research, conducted by The Guardian, Die Zeit and SourceMaterial, looked at forest carbon offsets approved by Verra – the world’s leading certifier of offsets for the voluntary market. It found that more than 90% of these certified rainforest offsets “did not represent genuine carbon reductions”.

2/ Of 2,000 major offset projects, only 12% led to real emissions reductions.

Systematic review of the actual emissions reductions of carbon offset projects across all major sectors, Benedict Probst, Malte Toetzke, Laura Diaz Anadon, Andreas Kontoleon, Volker, Hoffman, pre-print article, 2023.

Key Finding: This research looked surveyed existing empirical studies of more than 2,000 offset projects. The research looked at several different offset types, finding that 0% of offsets for renewable offsets let to real emissions reductions, 0.4% for cookstoves, 25% for forestry, and 27.5% for chemical processes. Overall, “88% of the total credit volume across these four sectors in the voluntary carbon market does not constitute real emissions reductions.”

3/ More than $700 million worth of Australian Carbon Credit Units leading to “very little change”.

Summary Results of Analysis of the Integrity Risk and Performance of Human-induced Regeneration (HIR) Projects using CEA data, Andrew Macintosh, Don Butler, Megan C. Evans, Marie Waschka and Dean Ansell, ANU, 2023.

Key Finding: This research looked at Australian Carbon Credit Unit (ACCUs) issued under the ‘Human-Induced Regeneration’ method. Generally, these credits are awarded where a change in grazing practices by landholders allows for tree cover to regenerate, thereby drawing down carbon. This research surveyed 189 HIR projects across Australia, and found that “the vast majority of HIR projects that have been credited to date have resulted in very little (and often negative) tree cover change”. As such, 24,600,748 ACCUs have been issued – worth $763 million at today’s prices – which have led to minimal, if any, carbon sequestration.

4/ Credits were granted for projects that would have happened anyway in UN-run Clean Development Mechanism

Do Carbon Offsets Offset Carbon? Raphael Calel, Jonathan Colmer, Antoine Dechezleprêtre, Matthieu Glachant, CESIFO Working Papers, 2021.

Key Finding: Under the UN-run Clean Development Mechanism, credits can be issued for renewable energy projects. This research surveyed 1,350 wind farms across India, considering whether they would have been viable without additional income from CDM credits. It found 52% of these projects would have been built anyway, meaning that “the sale of these offsets to regulated polluters has substantially increased global carbon dioxide emissions.”

5/ Inflated baselines lead to millions of junk carbon credits in a Zimbabwean avoided deforestation project.

The Great Cash-for-Carbon Hustle, Heidi Blake, The New Yorker, 2023.

Key Finding: Investigative reporting found that only fifteen million of the forty-two million carbon credits generated by a project in Zimbabwe represented legitimate avoided emissions. This investigation also raised questions about the share of benefits from carbon-credit income that went to local communities, compared to the company that ran the project.

6/ Junk ‘zombie’ offsets are being used being used to meet climate targets.

Data exclusive: The ‘junk’ carbon offsets revived by the Glasgow Pact Chloé Farand, Maribel Ángel-Moreno, Léopold Salzenstein and Jelena Malkowski, Climate Home News, 2022.

Key Finding: The world’s largest carbon offsetting program, the Clean Development Mechanism, has resulted in millions of carbon offsets with dubious climate benefits with some being associated with human rights abuses. Despite being over 10 years old these offsets are still being used to meet climate targets.

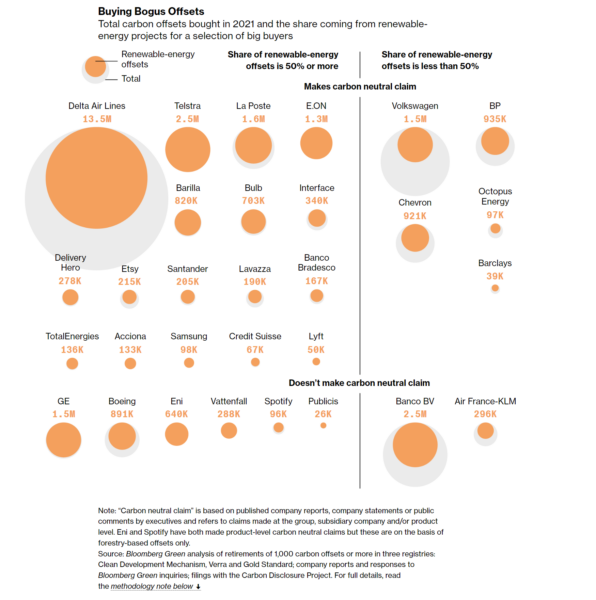

7/ The world’s biggest companies are making offsetting claims with old renewable energy projects.

Junk Carbon Offsets Are What Make These Big Companies ‘Carbon Neutral’ Akshat Rathi, Natasha White and Demetrios Pogkas, Bloomberg News, 2022.

Key Finding: One-third of the carbon offsets purchased from the 100 highest-selling projects in 2021 are tied to low-integrity renewable energy projects.

8/ Avoided deforestation projects do not avoid deforestation.

Action needed to make carbon offsets from forest conservation work for climate change mitigationThales A.P. West, et al., Science, 2023.

Key Finding: This research looked at the effects of 26 avoided-deforestation projects, across 6 countries – all part of the UN’s REDD program, which seeks to reduce emissions and enhance the removal of greenhouse gases through forest management. Researchers found that most projects have not significantly reduced deforestation” and that “for projects that did, reductions were substantially lower than claimed”. This raises serious questions about the integrity of global carbon accounting.

9/ Californian forest offsets may have actually increased emissions.

Little evidence of management change in California’s forest offset program, Jared Stapp, et al., Nature Communications: Earth & Environment, 2023.

Key Finding: This study looked at forest carbon offsets generated under the Californian state market. Analysis “failed to show additionality”, meaning that there no carbon emissions were reduced or offset by these projects. Following from this, “offsets increase net emissions if they do not reflect real emission reductions beyond the baseline scenario” – or, put simply, carbon offsets in California have resulted in increased emissions.

10/ Study finds that reduced deforestation credits “should not be treated as equivalent to fossil fuel emissions”

Quality Assessment of REDD+ Carbon Credit Project, Barbara K. Haya, et al., Berkeley Carbon Trading Project, 2023.

Key Finding: This major research project, developed by fourteen academics, assessed the effectiveness of REDD+ carbon crediting programs, all verified by Verra for the voluntary market. The research found that these REDD+ methods “generate credits that represent a small fraction of their claimed climate benefit. Estimates of emissions reductions were exaggerated across all quantification factors”. An implication of this is that “REDD+ credits should not be traded with, or treated as equivalent to, fossil fuel emissions.” In short, these carbon credits do not represent real emissions reductions.

11/ Research shows that forestry carbon offsets based on flawed science.

Comprehensive review of carbon quantification by improved forest management offset protocols, Barbara K. Haya, et al., Frontiers in Forests and Global Change, 2023.

Key Finding: Improved Forest Management (IFM) offsets have produced 11% of global voluntary offsets to date “deviate from scientific understanding related to baselines, leakage, risk of reversal, and the accounting of carbon in forests and harvested wood products, risking significant over-estimation of carbon offset credits.” Put simply, these offsets are based on dodgy science, and where used to justify the use of fossil fuels elsewhere, result in increased emissions.

12/ Half of the Amazonian forests that were issued carbon offsets to prevent deforestation have been cleared.

Why Carbon Credits For Forest Preservation May Be Worse Than Nothing, Lisa Song, ProPublica, 2019

Key Finding: This report drew on satellite imagery of projects that were granted carbon credits for avoided deforestation in Brazil – that is, projects that protected forests from being cleared. Four years later, half of these areas had been cleared.

13/ Researchers found Australia is at risk of failing on climate targets, as the Safeguard Mechanism relies on broken offsets.

Why offsets are not a viable alternative to cutting emissions, Climate Analytics, 2023.

Key Finding: This research considered the integrity of ACCUs, as well as their use as offsets under the Safeguard Mechanism. Researchers calculated when ACCUs are used to mitigate emissions from LNG production, for every tonne of emissions saved 8.4 tonnes are released. For coal the equivalent figure is 58-67 tCO2e. The key finding here is that offsetting fossil fuel extraction leads to significant downstream emissions, even if the credits have integrity.

14/ Papua New Guinea REDD+ project generates 800 million carbon credits, despite no evidence of imminent forest clearing.

Carbon cowboys and cattle ranches: Submission on the proposed REDD+ project in Oro Province of Papua New Guinea, Polly Hemming and Andrea Babon, The Australia Institute, 2022.

Key Finding: Research analyzed a project proposal for a large, avoided deforestation project in PNG, which was credited by Verra. Research found that “The proponents have not adequately or credibly justified their assumptions around the current rate of forest loss… Nor have they demonstrated how the forest is at imminent risk of clearing that would only be curbed by the existence of the project.”

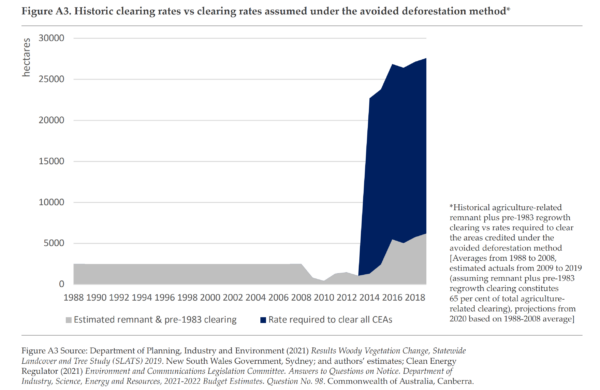

15/ Australian avoided-deforestation offsets assume an impossible increase in historic land clearing rates – of between 751 and 12,804 percent.

Questionable integrity: Non-additionality in the Emissions Reduction Fund’s Avoided Deforestation Method, Richie Merzian, Polly Hemming and Annica School, The Australia Institute and Australian Conservation Foundation, 2021.

Key Finding: This research looked at the avoided deforestation method in Australia. As of 2021, the Australian Government had bought 26.3 million ACCUs granted under this method, worth $310 million. The methodology used to create these credits was found to be fundamentally flawed, making heroic assumptions about future increases to land-clearing rates, of between 751 and 12,804 percent. Where these faulty credits are used to offset emissions elsewhere, total emissions continue to rise.

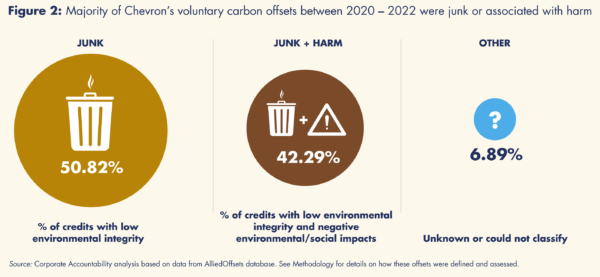

16/ 93% of the offsets used by fossil-fuel company Chevron to back up its ‘net-zero’ claims appear to be ‘junk’.

Destruction is at the heart of everything we do: Chevron’s junk climate action agenda and how it intensifies global harm, Rachel Rose Jackson and Adrien Tofighi-Niaki, Corporate Accountability, 2023.

Key Finding: Global fossil fuel giant Chevron has announced it will be ‘net zero’ by 2050. These claims rest on widespread use of carbon offsets and carbon capture and storage (CCUS) technologies. Both of these approaches are flawed: 93% of Chevron’s offsets have been found to have “low integrity”, and CCUS consistently fails to meet its targets – in some cases by 50%. Further, this study found that 42% of the carbon offsets used by Chevron are “linked to claims or allegations of inflicting harm on communities and spurring degradation of ecosystems, particularly in the Global South”. Finally, Chevron’s ‘net zero’ “aspiration” applies to only 10% of its emissions, leaving 90% unmitigated.

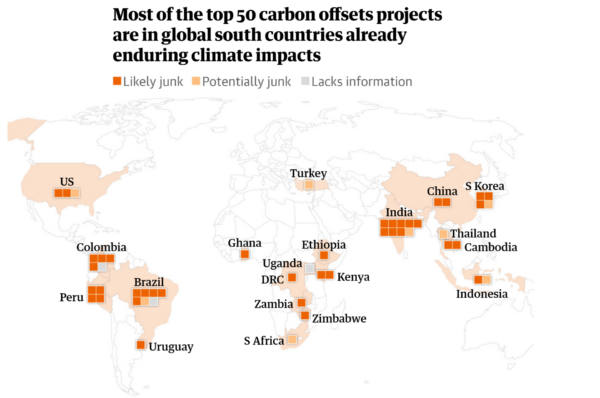

17/ Analysis finds that over $1 billion worth of carbon credits, from the global top 50 offset projects, are worthless.

Revealed: top carbon offset projects may not cut planet-heating emissions, Nina Lakhani, The Guardian and Corporate Accountability, 2023.

Key Finding: This analysis looked at the top 50 projects that have sold the most carbon offsets in the global market. The results found that 39 of these 50 projects, or 78% percent, were likely junk, and that eight others (16%) were problematic. The remaining 3 projects could not be assessed due to a lack of information. Projects were failed on various grounds, including: no additionality, exaggerated claims, inflated baselines, non-permanence, and leakage.

18/ Investigation found logging in forests that are supposed to be protected from deforestation.

Carbon colonialism, Stephen Long, Meghna Bali and Max Murch, ABC News, 2023.

Key Finding: This investigation looked at carbon offset projects, certified for the global voluntary market by Verra, in Papua New Guinea. Carbon credits from this project have been sold to the Sydney Opera House, Planet Ark, and Nespresso. But the forests that were supposed to be protected by these credits are being logged anyway. This ABC report also found that local communities were receiving less than a quarter of the returns from offset sales, with an Australian company taking the rest as profit.

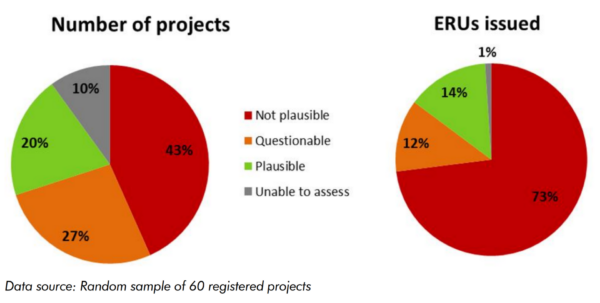

19/ Three-quarters of Kyoto Protocol Joint Implementation offsets are unlikely to represent real emission reduction.

Has Joint Implementation reduced GHG emissions? Lessons learned for the design of carbon market mechanisms, Anja Kollmuss, Lambert Schneider and Vladyslav Zhezherin, Stockholm Environment Institute, 2015.

Key Finding: This research considered the integrity of offset projects under the Kyoto Protocol, finding that three quarters of them were worthless. This analysis suggests that these offsets enabled around 600 million tonnes of additional greenhouse gas emissions– equivalent to a year of Australia’s total emissions.

20/ The Norway government has found that emissions reductions from REDD+ projects are delayed and uncertain.

The Office of the Auditor General of Norway’s investigation of Norway’s International Climate and Forest Initiative, Office of the Auditor General, Norway, 2018.

Key Finding: The government of Norway has been a leading contributor to the REDD+ offset scheme since 2008. This research by the Auditor General found that emissions reductions from these projects were delayed by local political struggles, and that the gains from these projects are uncertain.

21/ Oxford University researchers found more 27% of ‘biodiversity units’ at ‘high risk of non-delivery’

Achieving biodiversity net gain by addressing governance gaps underpinning ecological compensation policies, Emily E. Rampling, Sophus O. S. E. zu Ermgassen, Isobel Hawkins, Joseph W. Bull, Conservation Biology, 2023

Key Finding: The English government is introducing a requirement that new infrastructure developments demonstrate they achieve a Biodiversity Net Gain (BNG). 27% of all Biodiversity Net Gain units fall within governance gaps that expose them to a high risk of non-compliance.

22/ Le Monde found carbon credits purchased by companies including Samsung, Air France, and Boeing, did not actually represent offset emissions.

Brazil: Three carbon offset projects accused of being scams, Anne-Dominique Correa, Le Monde, 2023.

Key Finding: Verra-certified carbon offset projects in Portel, Brazil, were found to not represent the emissions reductions claimed, and their legality has also been called into question, with accusations of using public land they declared to be private.