South Korean lawmakers propose earlier coal phase-out in new 2030–35 bill

The country’s opposition moves to legislate a faster coal exit than the 2040 timeline cited at COP30, introducing a bill that would mandate a 2030–35 shutdown while ensuring a just transition for workers.

Bob Burton Coalwire:

Several South Korean MPs have drafted a bill requiring the closure of all coal power plants by 2035. The bill was drafted in consultation with the Coalition for the Enactment of the Coal Phase-out Law, a coalition of environmental, community, unions and progressive political parties. South Korea’s coal fleet has a combined capacity of 39.1 gigawatts (GW). The South Korean government recently announced that it has joined the Powering Past Coal Alliance and will close 40 of its 61 operating coal units by 2040, with the closure dates of the remaining 21 units set to be finalised in 2026. In the last four years, seven new units were commissioned: Shinseocheon Unit 1, Goseong High Units 1 and 2, Gangneung Eco Power Units 1 and 2, and Samcheok Blue Power Units 1 and 2. Each of the seven units has a capacity of 1 GW or slightly more, with three of the four plants built by private utilities.

By Taejun Kang Nov. 26, 2025 in ecobusiness.com

South Korean lawmakers have proposed a new bill to phase out all coal-fired power plants between 2030 and 2035, seeking to bring the country’s coal exit forward from the 2040 timeline that the government announced last week at the COP30 climate conference.

The initiative follows environment minister Kim Sung-hwan’s declaration at COP30 that South Korea, which operates the world’s seventh-largest coal fleet, would stop building new unabated coal plants and gradually retire existing ones. Out of the country’s 61 coal-fired power plants, 40 are already scheduled to close by 2040, Kim told delegates in Belém.

South Korea commits to coal phase-out, adding to clean energy momentum at COP30

This had been announced in tandem with Seoul formally joining the Powering Past Coal Alliance (PPCA), a coalition of more than 180 governments, companies and organisations committed to transitioning from unabated coal to clean energy.

Back in Seoul, opposition lawmakers are now pushing to lock in an earlier, legally binding timetable.

“The government has signalled its intention to phase out coal through its 2040 target and by joining the PPCA, but more proactive, early phase-out policies aligned with international trends and carbon neutrality goals are needed,” said Kim Jeong-ho, one of the lawmakers who proposed the bill that would require all coal plants to shut down between 2030 and 2035, with the exact schedule to be finalised by a new “Coal Phase-out Committee”.

The lawmakers said their aim was to create “a legal foundation that brings forward the coal phase-out timeline and ensures workers and local communities are not left behind, so that the nation can address the climate crisis and protect people’s lives”.

a legal foundation that … ensures workers and local communities are not left behind

The proposed law also seeks to guarantee the participation of power plant workers and local residents in the transition process through the Coal Phase-out Committee. It defines the responsibility of central and local governments to provide employment guarantees, job transfers and retraining, as well as support for shifting coal sites and workers into renewable energy.

“It is now time to make the shutdown of coal power a matter of law, not simply a declaration,” another lawmaker Seo Wang-jin said, calling the bill “a promise to safeguard the rights of future generations and respond responsibly to the climate crisis”.

It is now time to make the shutdown of coal power a matter of law, … to safeguard the rights of future generations

The proposed bill was drafted in consultation with civil society and labour groups, including the Coalition for the Enactment of the Coal Phase-out Law, a network of 75 organisations spanning environmental NGOs, local community groups, climate movements, trade unions and progressive parties. The bill must still clear committee review and a plenary vote before it can become law.

The lawmakers’ move came as international pressure for a faster coal exit mounts. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) have warned that the 1.5°C goal cannot be met without rapid reductions in coal power.

Separately, the International Energy Agency (IEA) says advanced economies need to end coal generation by 2030, while the G7 has pledged to phase out coal by 2035. Climate research group Climate Analytics has estimated that South Korea would have to retire coal completely by 2029 to remain aligned with the Paris Agreement.

the International Energy Agency (IEA) says advanced economies need to end coal generation by 2030, while the G7 has pledged to phase out coal by 2035

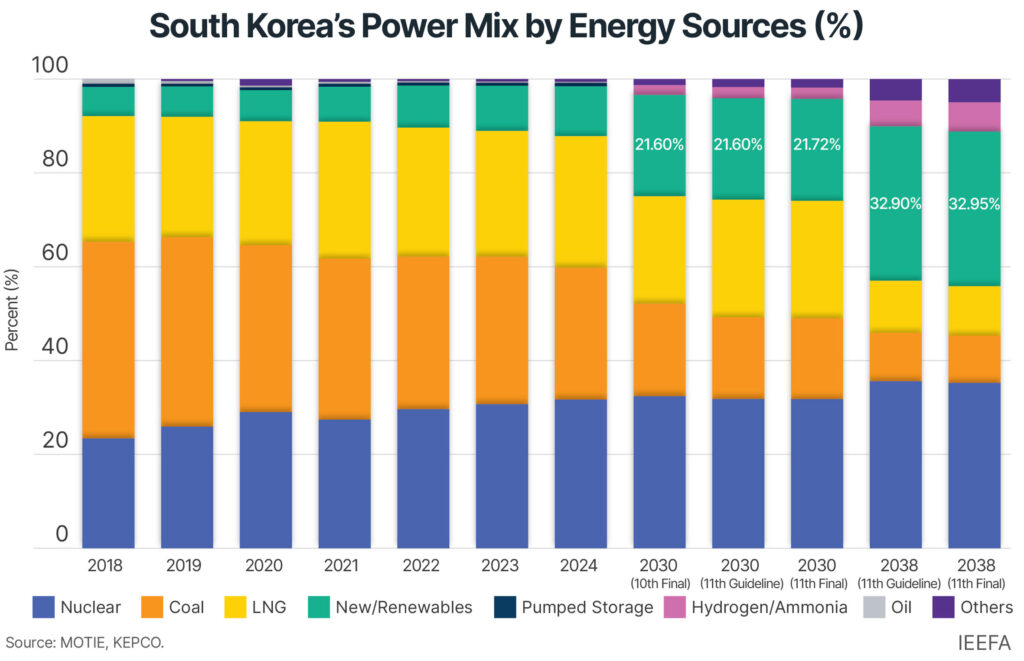

At COP30, the climate minister Kim said Seoul was “determined to foster renewable energy industries including wind, solar, battery energy storage systems (BESS) and the electricity grid,” noting that solar and wind currently make up less than 10 per cent of the country’s power mix.

South Korea recently announced a 2035 target to halve emissions from 2018 levels and is developing policies for a “more efficient power mix” in which renewables take a large share, with nuclear as a complementary source and gas as an emergency backup. Kim also highlighted up to US$20 million in low-interest loans pledged for greenhouse gas reduction projects.

But South Korean climate advocates say more is needed beyond coal. Public finance from South Korea still ranks among the world’s second-largest sources of fossil fuel funding, channelling about US$10 billion a year into oil and gas, according to non-profit Solutions for Our Climate. The group’s latest analysis suggests the shift to clean energy could double jobs and add more than US$7 trillion in economic value by 2035.

the shift to clean energy could double jobs and add more than US$7 trillion in economic value by 2035

17 Trillion Won New Coal Plants at Risk Under Climate Push

Government’s 2040 Coal Phase-Out Clashes With Recent Investments, Legal Risks

By Han Sam-hee 2025.12.01. in Chosun

The Ministry of Climate, Energy and Environment has begun formulating the 12th Basic Plan for Electricity Supply and Demand (2025–2040). Two key issues are at stake: whether the plan to build “two large-scale nuclear reactors and one small modular reactor (SMR),” included in the 11th iteration, will survive, and whether the pledge to phase out coal power generation by 2040 will be genuinely implemented. President Lee Jae-myung has repeatedly expressed skepticism about new nuclear construction, asking, “Will there be regions willing to accept it?” Minister Kim Sung-whan of the Climate and Energy Ministry, known as an anti-nuclear advocate, has raised significant doubts about the feasibility of proceeding with new nuclear projects.

The “2040 coal phase-out” was a campaign promise and included in the government’s September-announced national agenda. Minister Kim also declared South Korea’s accession to the Powering Past Coal Alliance (PPCA) at the 30th Conference of the Parties to the Climate Convention in Brazil last month, making it the second Asian country to join after Singapore. Given the consistent flow of campaign pledges, national tasks, and the PPCA commitment, the 2040 coal phase-out is likely to proceed forcefully.

Retiring aging coal plants is difficult to oppose due to their air pollution impact. However, seven coal plants completed in the past four years pose a different challenge. These include Shinseocheon Unit 1 in South Chungcheong Province (commenced operation in 2021), Goseong High 1 and 2 in South Gyeongsang Province (2021), Gangneung Eco Power 1 and 2 on the East Coast (2022–2023), and Samcheok Blue Power 1 and 2 (2024–2025). Except for Shinseocheon Unit 1, all are privately funded. Each of these seven 1-gigawatt (GW) ultra-supercritical facilities required approximately 2.5 trillion Korean won in investment, totaling around 17 trillion Korean won. Coal plants typically have a 30-year design lifespan, extendable by over a decade with upgrades. This means they could operate until the early 2050s or even the 2060s. However, under the 2040 phase-out policy, these new plants would be retired after just 15–20 years of operation. Compounding the issue, East Coast coal plants already faced low utilization rates of 17–18% last year due to insufficient grid infrastructure, as the East Coast–Singapyeong ultra-high-voltage direct current (HVDC) transmission line, originally slated for completion in 2019, remains unfinished.

The seven new plants were approved under the 6th Basic Plan for Electricity Supply and Demand in February 2013, during the final year of the Lee Myung-bak administration. At the time, nuclear expansion was unthinkable following the Fukushima disaster (March 2011). In September 2011, South Korea experienced unprecedented rolling blackouts due to power reserve shortages. As the Paris Agreement (2015) had not yet been signed, South Korea was not obligated to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The Lee Myung-bak administration had little choice.

Private investors received government approvals and proceeded with construction. The Moon Jae-in administration’s 8th and 9th plans also permitted these projects. If private investors file lawsuits, it is unclear what legal defenses the government could muster. Foreign investors might also seek compensation for damages caused by abrupt policy changes.

Reducing greenhouse gases is a global imperative, and South Korea must actively participate as a responsible member of the international community. However, such efforts require shared burdens among major economies. South Korea announced its “2035 NDC” at the climate conference, pledging to cut emissions by at least 53% (compared to 2018 levels) by 2035. Yet, a review of 113 countries’ 2035 NDCs submitted by the conference’s opening (November 10) showed an average reduction of only 12% (compared to 2019 levels). South Korea’s target is over four times stricter than the global average.

China’s greenhouse gas emissions are 20 times higher than South Korea’s and 1.5 times the combined total of the seven major Western nations. However, China’s 2035 NDC targets only a 7% reduction from its peak emissions, which is less than one-sixth of South Korea’s reduction relative to its 2022 emissions. While China has driven down costs for solar, wind, batteries, and electric vehicles, it continues to expand coal power. With 1,200 GW of coal capacity—30 times South Korea’s 39 GW—China is building an additional 204 GW. It has not joined the PPCA, nor have other major coal consumers like India and Japan.

There were concerns that the creation of the Climate and Energy Ministry would prioritize “climate defense” over “energy supply.” In an era where power supply capacity determines national competitiveness, decarbonization must align with global peers. A balanced approach is needed. Repeated calls for decarbonization while rejecting nuclear energy—a zero-carbon source—raise questions about the government’s true commitment to phasing out coal or achieving carbon neutrality.