Ditch premium to halve aviation emissions!

Article: Large carbon dioxide emissions avoidance potential in improved commercial air transport efficiency

- Stefan Gössling,

- Milan Klöwer,

- Jorge Cardoso Leitão,

- Sebastian Hirsch,

- Dietrich Brockhagen &

- Andreas Humpe

Communications Earth & Environment volume 7, Article number: 13 (2026) Cite this article

- 185 Altmetric

- Metrics details

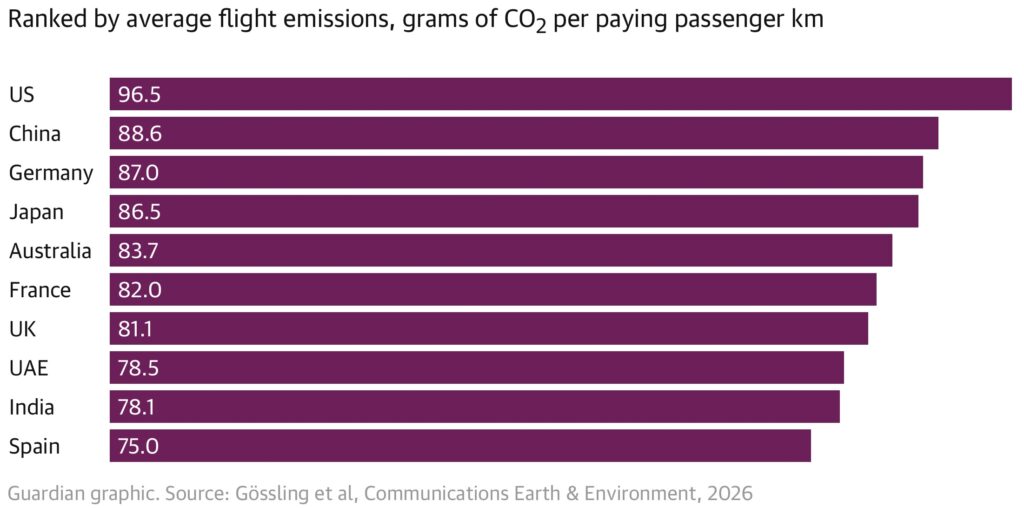

Gössling said replacing premium seats with denser economy seating was probably the most important factor. Overall, first and business class passengers are responsible for more than three times the emissions of economy passengers, he said, and up to 13 times more in the most spacious premium cabins. (Quote from The Guardian)

Abstract

Aviation’s climate impact continues to grow, with little progress toward emission reductions aligned with global targets. While technological advances attract attention, operational efficiency across aircraft, airlines, airports, city pairs, and regions remains underexplored. Here we assess carbon dioxide efficiency for 27.5 million flights between 26,156 city pairs in 2023, using data from Airline Data, International Civil Aviation Organization, International Air Transport Association. Results show wide variation: 32–890 gram carbon dioxide per revenue passenger kilometres across routes and 60–360 gram carbon dioxide per revenue passenger kilometre across aircraft models. Efficiency differs by region and is lowest in Africa, Australia, and Norway, and highest in Brazil, India, and Southeast Asia. Operating all routes at their demonstrated optimum could cut emissions by 10.7%. A theoretical 50% reduction is possible with the most efficient aircraft, all-economy layouts, and 95% load factors. Efficiency-focused policy could swiftly reduce fuel use without limiting air transport capacity.

from The Guardian based on Gossling et al. article.

Introduction

Global commercial aviation released between 892 and 936 Mt of carbon dioxide (CO₂) in 20191,2,3, contributing roughly 4% of the world’s net human-driven effective radiative forcing4,5. Industry projections indicate that the sector is likely to see robust growth over the next twenty years6,7. As demand growth has outpaced efficiency gains in the past, emissions from the sector will continue to rise unless new technologies, including sustainable aviation fuels (SAF), become available at scale8,9,10. However, with recent Airbus’ decision to delay work on hydrogen-electric aircraft; technical and economic barriers to e-fuel production11,12; and the cost and production limits to SAF13,14, it is unlikely that the sector will decarbonize in line with global climate stabilization objectives15,16.

Factors driving the growth of emissions in air transport include the expansion of airlines, airports, and the role of subsidies17, as well as patterns of flight distribution and the influence of frequent fliers on demand generation18. Less attention has been given to the potential for reducing emissions, including through improved fuel efficiency in the air transport system. Fuel consumption can be optimized in four general ways: aircraft technology & design; alternative fuels & fuel properties; aviation operations & infrastructure; and socio-economic & policy measures19. Aircraft technology & design refers to airframe (weight, aerodynamics) and engine fuel efficiency. New fuels with properties similar to Jet A1 will reduce net CO2emissions. Operations & infrastructure refers to optimized flight routes, including altitude, air traffic control systems, dynamic scheduling, efficient ground handling, airport designs and airport congestion20. Higher passenger load factors reduce fuel consumption per passenger, as do economy-class only seating configurations3,21,22. Regarding policies, subsidies make air transport less efficient23, while any form of charge directly or indirectly targeting emissions (SAF fuel quotas, landing fees, air passenger duties, emission trading) is an incentive for airlines to operate more efficiently. Efficiency gains will be an important pillar of any decarbonisation strategy for the sector24, although growth rates have consistently outpaced efficiency gains in the past25.

Historically, average passenger load factors have seen an upward trend, from 63.2% in 1980 to 82.4% in 2019, while emissions per RPK fell from 280 g CO₂ per RPK to 90 g CO₂ per RPK25. Yet, recent restrictions in airspace use due to military conflicts (specifically Russia-Ukraine) have increased flight distances and global fuel consumption26. Several large airlines have also started to introduce more premium travel options27, decreasing fuel efficiency. In the future, avoidance of super-saturated flight zones to reduce contrail formation and subsequent non-CO2 warming is projected to increase fuel use28, while the introduction of supersonic aircraft will decrease fuel efficiency and accelerate radiative forcing29.

While factors influencing fuel consumption have been discussed, differences in global operational efficiency appear to have never been investigated. We analyze passenger air transport efficiency between aircraft, airlines, airports, city pairs, and geographical regions. The potential of three strategies—operating only the most efficient aircraft, adopting an all-economy class configuration, increasing load factors—is assessed to determine the hypothetical maximum efficiency for the current air transport system.

Conclusions

Further growth in aviation will make the sector increasingly relevant for climate change mitigation. Efficiency gains have importance, because the replacement of Jet A1 with SAF does not eliminate non-CO₂ components, even though lower soot particle emissions can reduce effective radiative forcing31. Strategies minimizing fuel use are thus preferable, as they contribute to a reduction in CO₂ as well as non-CO₂ effects. This article highlights the considerable potential for efficiency gains in the sector: higher load-factors, the scaling back of premium-class seating, or the replacement of inefficient aircraft models with efficient ones provide opportunities for considerable fuel savings.

While airlines often claim that fuel savings are in their own economic interest, the reality is that many airlines continue to fly with old aircraft, low load factors, or growing shares of premium-class seating. For example, aircraft remain in service for 25 years32. Global passenger load factors have generally increased over time, but have yet to surpass the 85% threshold25. New policies and policy corrections are needed to accelerate efficiency gains in aviation. For example, low load factors may be a result of public service obligations and other subsidies provided by governments23, encouraging – and even forcing – airlines to fly even though demand is marginal. Another example is the hub-and-spoke model, under which airlines fly passengers from smaller airports to central hubs where they can transfer to other flights. Spoke routes may be served with smaller, less efficient aircraft, have lower load factors, and not be profitable on their own33.

Climate policies, where they exist, currently focus on decarbonizing air transport through the adoption of SAF. For example, the European Union’s ReFuel programme forces airlines to adopt greater shares of SAF34, defined as a percentage share of total fuel use. Paradoxically, this legislation could lead to an increase in overall warming, even if quotas are successfully met, if total fuel use increases faster than the share replaced with SAF. Inefficiency considerations in air transport are an alternative climate governance inroad: as the CO2intensity cap model illustrates, efficiency-based policies have a great potential to curb emissions. These may include soft policies (a public airline efficiency rating), market-based measures (phasing out subsidies, higher landing fees for inefficient airlines or aircraft), or regulatory approaches (CO2 intensity caps). Notably, there is precedent for such policies in other sectors: the EU energy label and minimum performance standards for white appliances35, bonus-malus systems in vehicle insurance36 or fuel economy standards37, as recently approved by the Marine Environment Protection Committee for international shipping38. Resistance to any such policies must be expected, as airlines operate within economic constraints, a business environment shaped by subsidies, expectations of continued growth, and limited ambition for climate change mitigation.