Fossil fuel firms may have to pay for climate damage under proposed UN tax

Framework Convention on International Tax Cooperation could also force ultra-rich to pay global wealth tax

Guardian Fossil fuels

Fiona Harvey and Heather StewartSun 1 Feb 2026 23.00 AEDTShare

Fossil fuel companies could be forced to pay some of the price of their damage to the climate, and the ultra-rich subjected to a global wealth tax, if new tax rules are agreed under the UN.

Negotiations on a planned global tax treaty will resume at the UN headquarters in New York on Monday, with dozens of countries supporting stronger rules that would make polluters pay for the impact of their activities.

dozens of countries supporting stronger rules that would make polluters pay

But developing countries are worried the current draft of the proposals is too weak, and want more robust backing from the rich world. Clear proposals on taxing the profits of fossil fuel companies have been watered down in their language, and proposals for a global asset registry that would help in taxing wealthy individuals have been removed from the text.

Marlene Nembhard Parker, main delegate for Jamaica at the negotiations for the UN Framework Convention on International Tax Cooperation, said: “In the context of Hurricane Melissa, which wiped the equivalent of 40% off our GDP overnight, it is time that the draft template text on sustainable development gets fleshed out. A much clearer link now needs to be made to environmental taxation and climate change, with clearer agreements on the actions that must be taken, nationally and internationally, particularly for the countries and industries who are most responsible.”

Negotiating the convention, which could be adopted as soon as the end of next year if countries can iron out details, was now urgent, she added, as more countries were afflicted by climate-related disasters. “This [tax] is critical for domestic resource mobilisation so that countries can sustainably rebuild and become resilient to increasingly devastating climate impacts, rather than become more dependent on borrowing and debt,” she told the Guardian. “There can be no sustainability without dealing with climate change in the way we design our global tax rules.”

“This [tax] is critical for domestic resource mobilisation so that countries can sustainably rebuild and become resilient to increasingly devastating climate impacts, rather than become more dependent on borrowing and debt,”

Progress on the tax treaty, which was first proposed by African countries in 2022, has been slow so far. The US has withdrawn from the talks, though this need not prevent other countries pressing ahead. Some rich countries have also argued that tax matters should be discussed within the OECD, of which only advanced economies are members, rather than within the UN, where all countries have a say.

If it can be made to work, the treaty could be a big step forward in making fossil fuel producers pay for the damage they cause, and in ensuring the richest contribute. Inequality rates have soared in recent years, with the wealthiest 0.001% of the population – roughly 56,000 people – holding three times more wealth than the poorer 50%, and the disparity is growing.

Sergio Chaparo Hernandez, of the Tax Justice Network (TJN), said, “The next round of talks in New York will be a real test: can member states craft international tax rules that are fit for the age of climate catastrophe?”

He added: “Civil society is pushing for the convention to include a clear mandate to advance progressive environmental taxation: making sure polluters pay, and that richer countries lead in ways that reduce global inequalities and support climate-resilient development in countries most affected – consistent with their historical responsibilities.”

Countries are losing $492bn (£359bn) a year in tax, as multinational corporations and wealthy individuals use tax havens to underpay, according to TJN. Oil and gas companies have made hundreds of billions in bumper profits in recent years, especially from the spike in prices that followed Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. According to Eurodad and the Global Alliance for Tax Justice, a 20% surtax on the profits of the 100 biggest producers would have yielded more than $1tn in the 10 years since the Paris climate agreement was signed in 2015.

Countries are losing $492bn (£359bn) a year in tax, as multinational corporations and wealthy individuals use tax havens to underpay,

For many of those most vulnerable to the climate crisis, taxing the companies that are driving the crisis is essential to achieving climate justice. Tapugao Falefou, Tuvalu’s permanent representative to the UN, said: “The responsibility lies with the world’s biggest polluters. The fossil fuel industry and the super-rich continue to increase their wealth while we try to keep our heads above water.”

Countries could impose taxes on fossil fuel consumption for themselves, and many do so, but only those where the extractive industries are based can put direct charges on its exploitation, hence the push for a global tax regime. Similarly, many countries are reluctant to consider wealth taxes, despite evidence of their success in some countries, for fear of putting the ultra-wealthy to flight, but if a large group of countries were to agree on minimum taxes on wealth it could help assuage such fears. An annual wealth tax of up to 5% on the ultra-rich would raise about $1.7tn a year.

The responsibility lies with the world’s biggest polluters. The fossil fuel industry and the super-rich

The UK had previously been regarded by campaigners as sceptical about whether the UN is the right locus for tax negotiations, but campaigners say it has recently taken a more positive approach, including endorsing the “polluter pays” principle.

A spokesperson for the UK’s Treasury said: “The UK has been an active participant in tax negotiations at the UN and remains committed to working constructively to ensure inclusive and effective international tax cooperation.”

An annual wealth tax of up to 5% on the ultra-rich would raise about $1.7tn a year.

Insights Decarbonization Energy Policy Australia Canada Indonesia Sweden Switzerland

IEEFA Australia: The case for introducing a carbon tax

March 15, 2022

Adrian Blundell-Wignall

As the evidence mounts every day that the worst is happening sooner than scientists expected, politicians of both parties in Australia skirt around having a meaningful climate policy – while pretending otherwise to voters.

The Prime Minister’s “Australian way” policy means moving to zero emissions without reliance on carbon taxes. Taxpayers’ money will be used to pay carbon credits to companies that do good things, such as not cutting trees and capturing and burying carbon (all on a “cash now, outcomes later” basis). Electricity prices won’t be allowed to skyrocket. Coal mining jobs will be protected.

Politicians skirt around having a meaningful climate policy – while pretending otherwise to voters

It’s already working, apparently. The government claims we are 20% down in carbon dioxide emissions if you take 2005 as a base year, right after broadscale land clearing in Queensland was abolished by a state Labor government in 2004. That’s clever. A tree chopped down puts carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. Just stop it and emissions are reduced compared with the year before.

That’s not what you get if you focus on industry carbon – the fossil fuel you burn and put into the atmosphere. Carbon emissions were up 5% by 2019 compared with 2005 (and down by only 2.7% in 2020 if anyone wants to take credit for the impact of COVID-19).

Our politicians repeatedly put out misleading claims, and spread fears. The truth becomes blurred for the average citizen. That’s anomie.

Let’s try to straighten the record just a little. The carbon we burn in producing our domestic GDP is about 400 million tonnes, about 1.1% of global emissions. But we consume far less than we produce, and the large excess (nearly four times what we consume) is sold abroad, where it is burned.

The combined amount of carbon released domestically and abroad from the burning of our fossil fuels is approximately 1.1 billion tonnes a year, roughly 4.3% of global emissions.

That’s enormous for a country that represents just over 1% of global GDP. The combined emissions are up 60% since 2005.

The country’s combined emissions are up 60% since 2005

Here is a simple truth. It doesn’t matter where the fossil fuel is burned. The carbon dioxide pumped into the atmosphere has exactly the same effect on climate change, regardless of whether it’s burned here or abroad. That’s what matters for our grandchildren.

Canada, another resource-rich country, is larger than Australia and might be expected to produce more carbon from its fossil fuels. Canada contributes about 3.1% globally. Now that’s nothing to be proud of – it exports a lot of oil to the U.S. – but for a resource-rich country it is doing better than us.

No meaningful climate policy

Australia is worse than Canada for two main reasons. First, we sell more of the really nasty stuff: coal. Second, we rank 60th out of 61 countries in the world on climate policy. The U.S., at 61st, is stone last.

We have nothing like a meaningful climate policy.

Canada, ranking 29th on policy, sets a minimum carbon tax, currently at $US32 per tonne and set to rise to $US170 by 2030. The regressivity of the carbon tax is addressed by tax rebates and revenue redistributions.

Australia’s Coalition government abolished the carbon pricing scheme of the Gillard government in 2014. Since then, it has repeated the mantra that putting a meaningful tax on carbon – notwithstanding that many countries have one – will destroy our Aussie way of life.

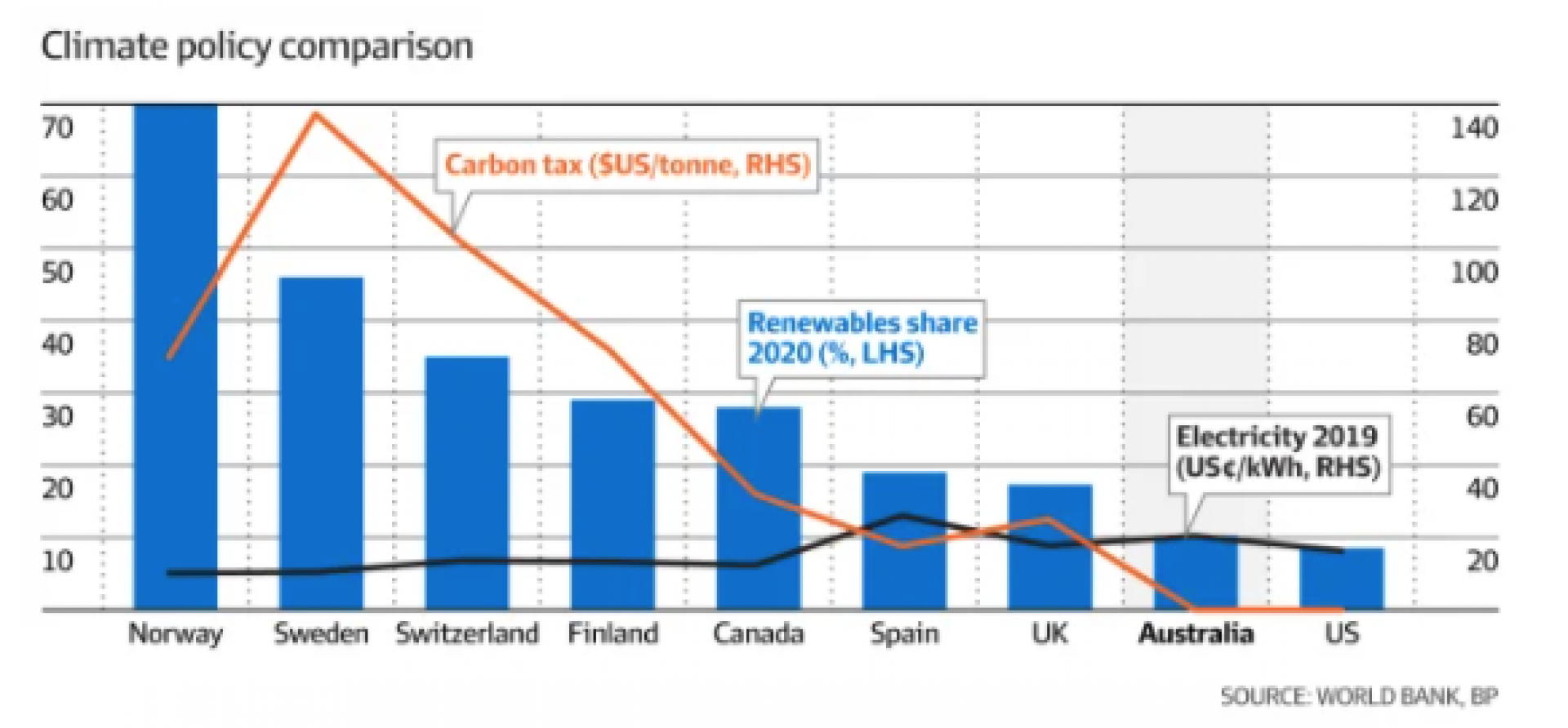

The progress Australia has made on renewable energy reflects where it sits on the climate policy ranking scale. The chart shows a selection of OECD economies that consume a significant quantity of energy (more than 1 billion gigajoules), with carbon taxation, renewable energy, and power prices compared.

No-tax Australia and no-tax U.S. sit at the bottom. The Scandinavian countries and Switzerland, facing very high carbon taxes (especially Sweden), sit at the top on green energy. These countries (and Canada) have very high living standards despite taxing carbon.

We take pride in exporting coal

In addition to refusing to tax carbon, the Federal government subsidises fossil fuels through tax breaks and grants. State governments also provide support for fossil-fuel power stations and port infrastructure to better supply coal and gas to the rest of the world.

Our current governments are actually proud of exporting coal: “Australia will keep selling coal for as long as the world keeps buying it” (Keith Pitt). It’s about digging out our huge reserves of coal (and gas) and selling it abroad before the world stops us from doing so.

With a carbon tax, other countries would buy less of our coal. That’s the whole point.

Phasing out coal and reducing subsidies should be central to our policy approach

Phasing out coal and pushing a national plan that accelerates our path towards renewable energy via taxes and reducing subsidies should be central to our policy approach. Help for coal mining families to transition to other sectors that have a future would be a counterpart to this approach.

It speaks volumes that entrepreneurs such as Twiggy Forrest have stepped in, or Mike Cannon-Brookes before withdrawing his AGL bid this week. They aren’t doing it because of moral values. It’s because it makes economic sense. They are not constrained by trying to hold on to power in marginal seats while holding together fragile political alliances.

A sound climate policy would broaden and accelerate these sorts of investments and act to reduce electricity prices (not increase them) because renewables are much cheaper.

The blue line on the chart shows that higher carbon tax and renewables are associated with lower electricity prices.

Meaningful climate policy won’t be part of the coming election

Both parties have projects such as public money for electric cars, solar power and batteries. Nothing wrong with that. But the policies are not in place to catch up with what some other important OECD countries have already achieved. Anomie reigns.

The blurring of basic truths on both sides of politics means, sadly, that meaningful climate policy won’t be part of the coming election. Cannon-Brookes and others have attempted to do things that make sense, but without policy leadership it won’t improve the climate outlook for our grandchildren quickly enough.

An Australian carbon tax and global co-operation on border taxes are essential for achieving that goal.

By IEEFA guest contributor Adrian Blundell-Wignall

This excerpt is from a commentary that first appeared in the AFR.

Related articles:

IEEFA: Postcard from 2030. Energy is clean, finance is moral, wish you were here

IEEFA Australia: How fossil fuel subsidies are thwarting Queensland’s renewable energy ambitions

IEEFA: The cash hit-list to counter climate change

Adrian Blundell-Wignall

Adrian Blundell-Wignall is a guest contributor at IEEFA.

Related Content

Building credibility in Indonesia’s energy transition: Insights from the ETM and JETP Indonesia

Mutya Yustika, Ramnath N. Iyer

Briefing Note Union Budget 2026: Strong fiscal signals, fragmented support for India’s energy transitionFebruary 04, 2026Vibhuti Garg Insights Submission: Preparing for emerging industries across Northern AustraliaFebruary 04, 2026Kevin Morrison, Kaira Rakheja Testimony | Submission Getting Bangladesh’s renewable energy transition on trackFebruary 03, 2026Shafiqul Alam Insights

In India’s EV success, a blueprint for adoption of e-cooking

Insights Momentum shifts east in green steel transitionFebruary 02, 2026Simon Nicholas Insights How credit ratings can undermine climate finance for the global southJanuary 30, 2026Subham Shrivastava, Labanya Prakash Jena Insights Bridging the net-zero gapJanuary 30, 2026Shantanu Srivastava, Tanya Rana Report

Cutting Australian mining’s diesel emissions

Briefing Note Budget 2026: Leveraging the clean energy transition to contain rising energy subsidies January 29, 2026Purva Jain, Vibhuti Garg Insights Offshore wind stop-work orders are costing consumers, delaying needed electricityJanuary 28, 2026Seth Feaster, Dennis Wamsted Insights Uganda’s oil industry is delayed, over budget, and results are likely to fall shortJanuary 28, 2026Fact Sheet

Climate-resilient development in Uganda

Matthew Huxham, Will Scargill, Gaurav Upadhyay…

Report Reassessing oil in UgandaJanuary 28, 2026Matthew Huxham, Will Scargill Report Oman forges ahead as a green iron and steel hubJanuary 26, 2026Soroush Basirat Insights

Join our newsletter

Keep up to date with all the latest from IEEFA

Footer menu

Newsroom

All NewsPress ReleasesIEEFA in the MediaMedia Inquiries

Research

All ResearchInsightsReportsBriefing NoteFact Sheets

About

What We DoWho We AreConferenceEmployment

Get in Touch

Contact us

INSTITUTE FOR ENERGY ECONOMICS AND FINANCIAL ANALYSIS

PO Box 472, Valley City, OH

44280-0472 USA

T: +1-216-353-7344

E: staff@ieefa.org

© 2025 Institute for Energy Economics & Financial Analysis.