The quiet power of safeguarding the wild

A pause in the Anthropocene led to an eagle baby boom

Decades of monitoring failed to detect it, but the Covid lockdown showed that human activity—not just predators or habitat—has been quietly stifling Bonelli’s eagle reproduction.

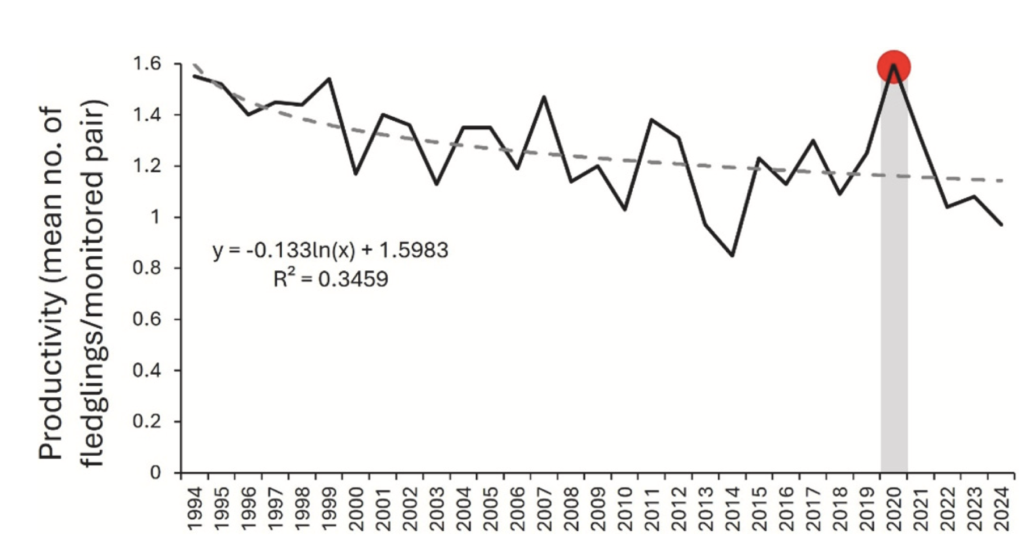

province of Granada, southeastern Spain, during the period 1994–2024. The

regression line is represented by a dashed line. To enhance clarity, the productivity

in the year of the COVID-19 lockdown (2020) is highlighted with a red

circle and a shaded area.

Gil Sánchez, et. al. “The COVID-19 lockdown unmasked the overwhelming impact of human activity on the breeding success of an endangered raptor.” Biological Conservation. Nov. 2025

December 3, 2025

Humans are so enmeshed with the lives of wild creatures, it can be hard even for scientists to see when our presence is causing problems.

For three decades, scientists have tracked Bonelli’s eagles in southern Spain. The area is home to much of the endangered European population of the massive bird, which can sport a nearly six-foot long wingspan. But even there it faces numerous threats, and productivity has been declining since scientists started following the birds in 1994.

Previous research has pointed to four main problems: territorial conflicts among individuals in the species; clashes with golden eagles; nests in colder, north-facing cliffs; and lead poisoning from eating game birds shot by hunters.

But it took the lockdown early in the COVID pandemic to help scientists at Granada University realize that they had been overlooking a major driver of poor reproduction rates: Human activity close to nesting eagles.

Humans had been so omnipresent throughout other years, that their effect on the birds was rendered invisible. Then, in early 2020, virtually all outdoor activity was banned in Spain as public health officials tried to slow the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. For months, the birds experienced surroundings largely devoid of the din of the Anthropocene.

Scientists around the world have tried to document the effect of the lockdown on the natural world, dubbed the “Anthropause”, with varying degrees of success. Anecdotes of wildlife running free in urban centers made their way through social media. The research-based findings were more mixed. One global analysis of wildlife cameras found that some animals became more active as humans stayed inside, while others actually moved around less.

Where would birds be without us?

But fewer studies documented changes in more detailed ecological dynamics, which are often where real effects are felt by animals. Did certain species fare better or worse?

In the case of Bonelli’s eagles, they did much better. The lockdown coincided with critical moments in the lives of eagle nestlings, which hatch in the early spring. Over 30 years, eagle pairs have, on average, produced 1.26 offspring in a year. But in 2020, that number rose to 1.6, a dramatic (and statistically significant) 27% increase. In the following four years, after the lockdown ended, productivity fell back to normal, the researchers reported in Biological Conservation.

What drove this sudden baby boom? To figure it out, the scientists looked at how the productivity at individual nests coincided with the usual suspects – golden eagles, diet, etc. But they also measured how close the nests were to sources of human activity, such as roads and paths. And they checked for the presence of human activities within 500 meters of a nest, including partridge hunting, traffic, hiking and cycling.

The analysis revealed that proximity to human activities was a primary factor in the productivity difference between 2020 and other years. Partridge hunting and traffic stood out as having the strongest effect. “Remarkably, the influence of these disturbances had remained largely undetected, despite three decades of monitoring,” the scientists wrote.

There are a few ways these activities might cause problems. Hunting might scare off eagle prey or change prey behavior; it might disturb the eagles themselves; and in extreme cases the eagles can get shot if they attack caged partridges that hunters use to lure wild partridges. Traffic, meanwhile, is associated with activities such as hiking that can bother the birds.

The new insight opens the door to measures that might boost eagle numbers. Conservation efforts should focus on restricting human access to nesting areas and tightening hunting regulations, particularly the use of lures by partridge hunters, the scientists write.

That will probably be more effective than waiting for another pandemic.

Gil Sánchez, et. al. “The COVID-19 lockdown unmasked the overwhelming impact of human activity on the breeding success of an endangered raptor.” Biological Conservation. Nov. 2025.