Download an amateur bird watcher app!

If you listen closely in Kentucky, you can hear the rainforest in southern Mexico.

A new analysis of billions of amateur bird sightings reveals the dependence of North America’s songbirds on a handful of Central American forests.

November 26, 2025 Anthropocene

The hills of Kentucky might seem like a separate world from the Selva Maya rainforest in Central America. But they are just a song away.

When someone hears the twitter of the tiny Kentucky warbler in the woods of Appalachia, the sounds are inextricably linked to what’s happening to this imperiled jungle in southern Mexico, Guatemala and Belize.

That connection, spanning thousands of kilometers, is being highlighted by scientists who used amateur bird sightings to illuminate the ties between birds that capture the hearts of North American birders and Central and South American forests threatened by deforestation.

“If we lose the last great forests of Central America—and we are—we lose the birds that define our eastern forests in North America,” said Jeremy Radachowsky, an ecologist involved in the new research as head of the Wildlife Conservation Society’s Mesoamerica program.

It’s not news that hundreds of bird species head south to escape North America’s winters, much as human sun birds flock to Palm Springs. Nor is it a surprise to hear that Latin American tropical forests are disappearing at an alarming rate, much of it to create grazing land for cattle. The statistics are grim: North American has lost an estimated 2.5 billion migratory birds from more than 400 species over the last half century. The five largest tropical forests in Mexico and Central America—an area equal to all of Virginia – have shrunk by between 5% and 30% in the last 25 years.

The new work by Radachowsky and colleagues at the society and Cornell University seeks to break through the lifeless abstraction of these numbers by putting a face—and feathers—on the problem, and to show people in wealthy, political powerful North America that they have a personal stake in what’s happening to the forests of their southern neighbors.

To do that, the scientists turned to eBird, an online birding hub run by Cornell University’s legendary ornithology lab. There, amateur birders have recorded billions of bird sightings from around the world, providing a vast trove of data for scientists to mine.

For some birds, a “taxi” helps recalibrate out-of-sync migrations

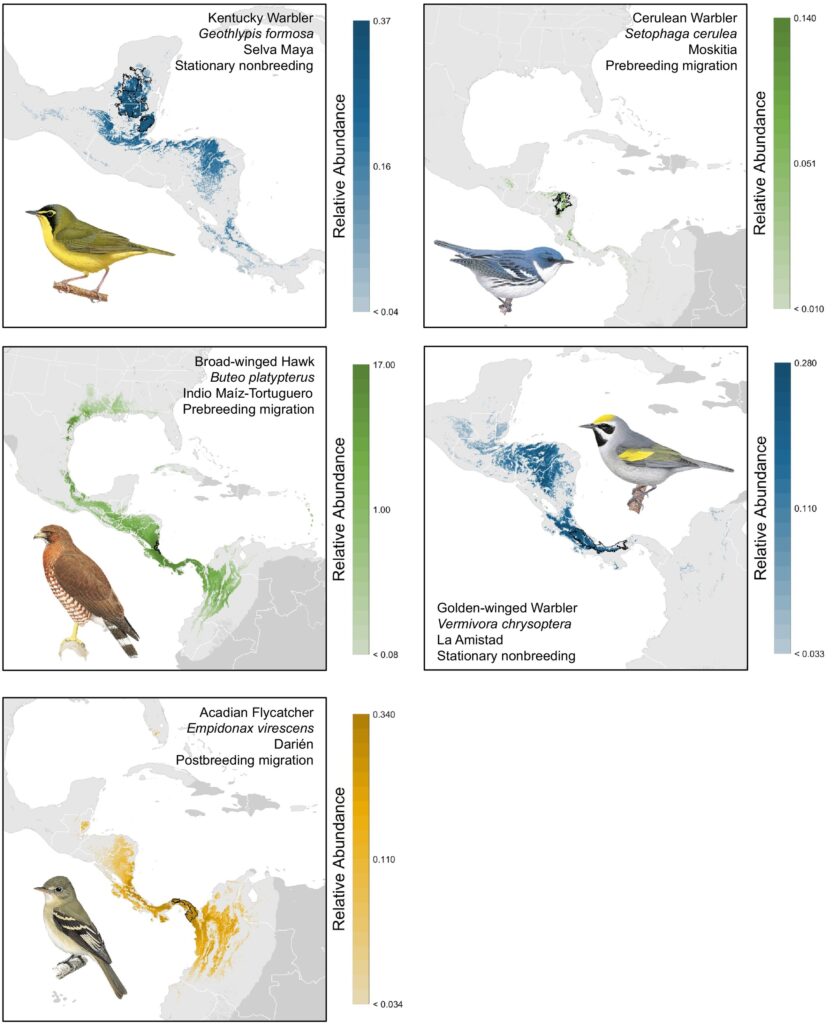

In this case, researchers wanted to trace how migratory birds moved between North America and forests to the south, with a particular focus on what the conservation society calls Mesoamerica’s “Five Great Forests”— the Selva Maya, the Moskitia in Nicaraqgua and Honduras, the Indio Maíz-Tortuguero in Costa Rica and Nicaragua, the La Amistad of Costa Rica and Panama, and the Darién in Panama and Colombia.

They used computer models to translate the collection of individual bird sightings from 2022 throughout much of the Americas into a picture of the numbers of birds from individual species in any place at a given time.

The data revealed that at least 163 different migratory species passed through or stayed in one of these five forests. Of that, 40 species had at least 10% of their global population in those forests for at least one week of the year, and 20% or more of the populations of 16 of those species, scientists reported last week in Biological Conservation.

“Every fall, billions of birds pour south through the narrow land bridge of Central America,” said Viviana Ruiz Gutierrez, director of Conservation Science at the Cornell lab and a co-author. “The density of migratory warblers, flycatchers, and vireos crowded into these five forests is astounding, and means that each hectare protected there safeguards a disproportionate number of birds.”

The tiny, lemon-yellow Kentucky warbler stands out. At the peak of the season, nearly half of its total population (46%) turned up in one of these five forests, chiefly the Selva Maya. Almost a third of the world’s cerulean warblers, named for their deep blue coloring, were passing through the Moskitia in early April as they headed north. Both species are in decline, as are these forests.

By clarifying how these distant places are linked through individual species – what the scientists termed “sister landscapes” – the scientists hope the research could help foster conservation efforts that cross political boundaries. Among other things, bringing resources from far away to boost local efforts “so that we can work together across the Americas to bring back our shared migratory birds,” says Gutierrez.

Lello-Smith, et. al. “Leveraging participatory science data to guide cross-border conservation of migratory birds: A case study from Mesoamerica’s Five Great Forests.” Biological Conservation. Nov. 19, 2025.

Highlights

- •Quantified migratory bird concentrations at nonbreeding sites with eBird information

- •Mesoamerica’s 5 Great Forests support 10–46 % of the populations of 40 migratory birds

- •“Sister” breeding regions identified via abundance concentrations of shared species

- •Demonstrate data-driven approach to guide international investments and partnerships

Abstract

With extinction risk for migratory species increasing globally, there is urgent need to safeguard the most important places used by migrants throughout their annual cycles. This requires prioritizing key sites and strengthening international collaboration and investment in less wealthy regions; yet progress has been limited by incomplete knowledge of how sites contribute to sustaining migratory populations and how sites are connected across seasons. Focusing on Mesoamerica’s Five Great Forests (5GF) – the region’s largest remaining and urgently threatened forests – we illustrate how information derived from the eBird participatory science platform can be used to assess the importance of nonbreeding sites for migratory birds and to identify “stewardship connections” between Mesoamerica and North America, based on abundance concentrations of shared species. We found that the 5GF support 20–46 % of the global populations of 16 Nearctic-Neotropical migratory species and ≥ 10 % of another 24 species outside of the breeding season. Key breeding grounds with stewardship connections to the 5GF include densely forested parts of the Northeastern U.S., Ontario and Québec, Minnesota and Wisconsin, the Mississippi Delta and Appalachian regions, and the Texas Hill Country. Our results provide evidence of the role of the 5GF as anchor points for migratory bird conservation and offer a powerful, data-driven communication tool to guide international investments and partnerships to protect these vital sites. More broadly, we demonstrate a flexible approach for leveraging participatory science information to identify cross-border connections around suites of shared species, with the aim of accelerating joint habitat stewardship for migratory birds.