1. Introduction

Earth’s inhabitants are threatened by several serious or existential crises: environmental, human health, social justice, loss of democratic decision-making, and nuclear war. In terms of environmental threats, human activities have exceeded six of the nine planetary boundaries defined by Earth system science and are approaching the boundary in a seventh (Stockholm Resilience Centre, 2022). In addition to the environmental threats, the gap between the rich and the poor has been increasing, both within and between countries (Chancel et al., Reference Chancel, Piketty, Saez and Zucman2022; Piketty, Reference Piketty2014; World Economic Forum, 2022). At the time of writing, June 2024, the COVID-19 pandemic has killed over seven million people (WHO, n.d.) and the poorest countries are still experiencing shortages of medical personnel and vaccines (Padma, Reference Padma2021). The inadequately regulated arms trade is increasing the risk of war. Based mainly on the risks of nuclear war and climate change, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists has set the Doomsday Clock to 90 seconds before midnight, ‘because humanity continues to face an unprecedented level of danger’ (Science & Security Board, 2024).

These global threats must be mitigated urgently to avoid dangerous irreversible changes to climate, public health, peace, and social structure (Armstrong McKay et al., Reference Armstrong McKay, Staal, Abrams, Winkelmann, Sakschewski, Loriani, Fetzer, Cornell, Rockström and Lenton2022; Bardi & Alvarez Pereira, Reference Bardi and Alvarez Pereira2022; Brand-Correa et al., Reference Brand-Correa, Brook, Büchs, Meier, Naik and O’Neill2022; Guterres, Reference Guterres2022; Lenton et al., Reference Lenton, Rockström, Gaffney, Rahmstorf, Richardson, Steffen and Schellnhuber2019). But if humanity focuses only on specific threats, it will fail to come to grips with the underlying driving forces, namely the political power of vested interests (e.g. mining, property, financial services, tobacco, and armaments industries) that have dominated government policies in many nation-states and some international organizations in a process known as ‘state capture’ (Chipkin et al., Reference Chipkin, Swilling, Bhorat, Buthelezi, Duma, Friedenstein, Mondi, Peter, Prins and Qobo2018; Dávid-Barrett, Reference Dávid-Barrett2023; Diesendorf & Taylor, Reference Diesendorf and Taylor2023; Klein, Reference Klein2014; Lucas, Reference Lucas2021). One of the tools used by vested interests in state capture comprises the intellectual framework and ideology that justify and support their power, that is, the dominant model of the real economic system. This model is neoclassical economics (NCE) theory together with neoliberalism practice, both defined in the box. This system is substantially based on exploiting the natural environment and most of the world’s human population (Fremstad & Paul, Reference Fremstad and Paul2022; Hickel, Reference Hickel2020; Klein, Reference Klein2014; Sanders, Reference Sanders2016).

These and other critiques of the assumptions, hypotheses, and claims of NCE in books and ‘alternative’ economics journals (e.g. Ackerman, Reference Ackerman2018; Daly & Cobb, Reference Daly and Cobb1990; Davies, Reference Davies2019; Denniss, Reference Denniss2016; Keen, Reference Keen2011; Martins, Reference Martins2016; Quiggin, Reference Quiggin2010; Self, Reference Self1993; Syll, Reference Syll2015; Waring, Reference Waring1988) have had little impact on the teaching of economics in universities, textbooks, publications in leading economics journals, or the public and political discussion of economic issues. Neither have critiques of theoretical, methodological, and policy aspects of NCE by established ‘conventional’ economists, for example, critiques of: Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium models (Stiglitz, Reference Stiglitz2018); NCE treatments of inflation and unemployment (Galbraith, Reference Galbraith2001); the instrumentalist approach to NCE (Lawson, Reference Lawson2001); and the misuse of GDP (Stiglitz et al., Reference Stiglitz, Sen and Fitoussi2010). However, it is unclear whether these authors consider themselves as neoclassical (NC) economists.

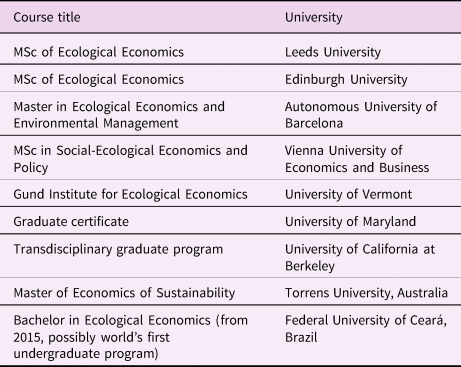

Although the transdisciplinary field of ecological economics focuses directly on achieving planetary and public health and social justice and has grown rapidly since the 1970s, resistance by influential NC economists has ensured that ecological economics, political economy and other ‘heterodox’ approaches to economics have been accepted by only a few Western universities worldwide (see Table 1), have been excluded from prestigious economics journals and have had little public or political impact (Butler et al., Reference Butler, Jones and Stilwell2009; Galbraith, Reference Galbraith2001; Lee, Reference Lee2004; Saith, Reference Saith2022). ‘Leading active members of today’s economics profession, the generation presently in their 40s and 50s, have joined together into a kind of politburo for correct economic thinking’ (Galbraith, Reference Galbraith2001). Scientist critics of NCE are rare – we are aware of three: Blatt (Reference Blatt1983), Philip Smith in Smith and Max-Neef (Reference Smith and Max-Neef2011) and Davies (Reference Davies2019).

Table 1. Majora university courses in ecological economics worldwide, 2024

In view of the critical situation outlined above, the aim of this paper is to offer a critique, from a scientific standpoint, of NCE and the myths it fosters through the ideology of neoliberalism. The principal audience envisaged comprises scientists and researchers other than NC economists working on sustainability problems, however the paper has been written to be accessible to the general public as well. While critiques of single issues in NCE have been published previously as research papers in peer-reviewed journals by economists, both neoclassical and heterodox, these do not provide an overview of many issues that, taken together, challenge systematically the rational scientific basis of NCE.

Our method is to review critically ten key hypotheses and four claims of NCE, on the grounds that they are either (a) contradicted by observation, (b) lead to different results from those reported by NCE, (c) are ill-defined, or (d) are internally inconsistent. Hence, we argue that NCE is fundamentally flawed and must no longer be used as the basis for government socioeconomic policies. We note that the distinction between a poorly justified hypothesis and a claim is not sharp.

The authors of the present paper are four interdisciplinary sustainability researchers trained in scientific disciplines, including one with also a PhD in economics, and an ecological economist. Before outlining our critique, we provide a list of definitions in the box.

Glossary of selected neoclassical economics terms

These definitions are drawn from NCE textbooks and re-interpreted using a critical, scientific perspective. Much of the NCE terminology takes words from the physical sciences – for example, force, equilibrium, efficiency – and gives them new meanings that can be subjective and misleading.

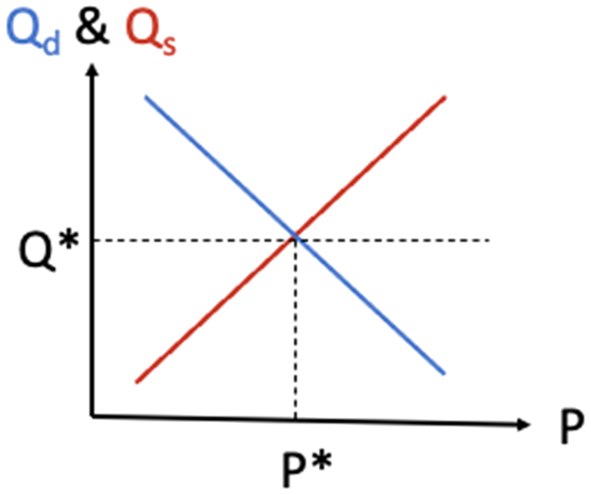

Neoclassical economics (NCE) is a broad theoretical structure that focuses on market supply and demand as the driving ‘forces’ behind the production, pricing, and consumption of goods and services. It assumes that people have ‘rational’ preferences, that they compete to maximize a concept called ‘utility’, and that decisions are made at the margin (i.e. valuing an addition of something and ignoring sunk costs). It ignores the roles of social interactions, culture and institutions in the economy and plays down the role of money, private debt and profits. It treats the environment as, in effect, an infinite resource and an infinite reservoir for waste. For a more precise, more concise definition, see Section 3.1.

Neoliberalism is economic practice that is based mainly on the theoretical hypotheses of NCE to argue for leaving most major socioeconomic decisions to the market and hence for free trade, low taxes, low regulation, and low government spending, except on defence. In neoliberalism, government exists to maintain property rights, support capitalists, and maintain price stability. Critiques for non-specialist readers are Mirowski (Reference Mirowski2014) and Hutchison and Monbiot (Reference Hutchison and Monbiot2024).

Homo economicus is a notional human being that is entirely self-interested and ‘rational’ in the sense of economics and can process all available information. Their preferences are exogenous, i.e. beyond the scope of economics.

Rational behavior is a decision-making process that is based on making choices that result in the maximum level of ‘utility’ for an individual.

Utility was originally introduced as a subjective measure of total satisfaction and individual gains from consuming a good or service. Nowadays, a utility function is a numerical representation of a preference ordering with no psychological connotation (Hands, Reference Hands2010).

Efficiency in NCE is understood in different ways – here are the two most prominent versions:

-

1. A state of the market is called Pareto efficient (or Pareto optimal) if there is no alternative state where improvements can be made to at least one participant’s ‘well-being’ or ‘welfare’ without reducing any other participant’s. In this state, resources are allegedly allocated in the most economically efficient way.

-

2. An economic transaction that produces or purchases or allocates goods or services for low cost or low physical inputs per item.

Market forces are not physical forces but simply factors that influence the price and availability of goods and services. NCE identifies these factors as supply and demand, but underlying them are many other factors such as government policies, advertising, fashion, personal preference, weather, speculation, population number, international transactions, energy availability, infrastructure, and the levels of public and private debt.

General equilibrium is an idealized state of the economy where demand and supply are equal for all markets in the economy. Many NC economists assume that market ‘forces’ tend to drive economies towards ‘general equilibrium’ and, contrary to clear evidence, that the equilibrium is unique and stable. In NCE ‘equilibrium’ includes ‘dynamic equilibrium’ or ‘balanced growth’, where demand and supply are still equal as the economy grows.

A free (or perfect) market is an idealized economic system, free from government interventions and other external constraints, and controlled by privately owned businesses. It does not exist in real industrial societies because the market is shaped by laws on powers of a corporation, banking and investment, government budgets, trade and consumer protection, and taxation.

Constant returns to scale is an economic condition where an increase in a business’s inputs, like capital and labor, increases its outputs at the same rate as the inputs.

An externality is a cost or benefit caused by a producer that is not financially incurred or received by that producer: e.g. carbon emissions by a steelworks in the absence of a carbon price.

Methodological individualism assumes that socioeconomic phenomena can be described in terms of subjective personal motivations by individual actors not influenced by other actors or the society to which they belong.

Methodological instrumentalism: theories are interpreted merely as practical tools or instruments for some purpose other than causal explanation.