Male mosquitoes to be genetically engineered to poison females with semen

Published:

Recombinant venom proteins in insect seminal fluid reduce female lifespan

Nature Communications volume 16, Article number: 219 (2025)

Abstract

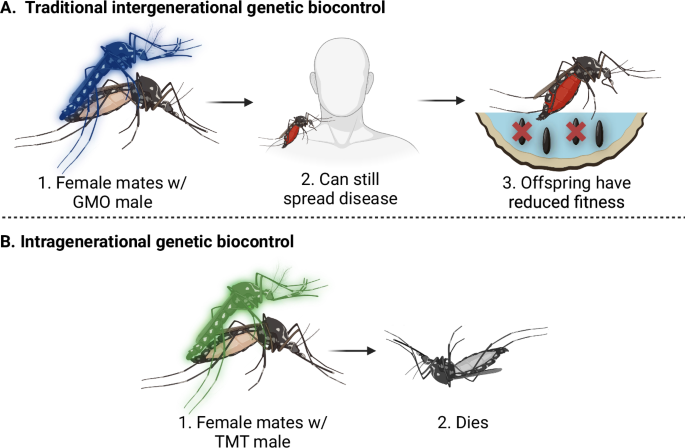

The emergence of insecticide resistance has increased the need for alternative pest management tools. Numerous genetic biocontrol approaches, which involve the release of genetically modified organisms to control pest populations, are in various stages of development to provide highly targeted pest control. However, all current mating-based genetic biocontrol technologies function by releasing engineered males which skew sex-ratios or reduce offspring viability in subsequent generations which leaves mated females to continue to cause harm (e.g. transmit disease). Here, we demonstrate intragenerational genetic biocontrol, wherein mating with engineered males reduces female lifespan. The toxic male technique (TMT) involves the heterologous expression of insecticidal proteins within the male reproductive tract that are transferred to females via mating. In this study, we demonstrate TMT in Drosophila melanogaster males, which reduce the median lifespan of mated females by 37 − 64% compared to controls mated to wild type males. Agent-based models of Aedes aegyptipredict that TMT could reduce rates of blood feeding by a further 40 – 60% during release periods compared to leading biocontrol technologies like fsRIDL. TMT is a promising approach for combatting outbreaks of disease vectors and agricultural pests.

Introduction

Insect pests pose a major challenge to human and environmental health. Malaria, spread by several species of Anopheles mosquitoes, causes 608,000 deaths per year1 and rates of arboviral diseases spread primarily by the Aedes aegypti mosquito, including dengue, Zika, chikungunya, and yellow fever, are reaching unprecedented levels due to increased global trade and warming climates2. Dengue virus alone causes 390 million human infections each year and is now considered the most common vector-borne viral infection worldwide3. Recent studies have calculated that the cumulative cost of biological invasions is increasing four-fold every decade4, with a conservative estimate of US$162.7 billion for damages caused in 20175. Invertebrate pests, primarily insects, are responsible for ~40% of these damages5,6, and estimates of annual losses for all major food crops ranges between 20 and 30% due to damages by pests and pathogens7. Arboviral diseases such as avian malaria also pose a significant ecological threat to many native species, and are believed to be a key driver of population decline in New Zealand and Hawaiian forest birds8,9.

Pesticides are the first line of defence against many invasive species, particularly mosquitoes10. However, over-reliance on insecticides has resulted in the widespread emergence of resistance11. Over-application of insecticides has also resulted in declining populations of non-target species, and are responsible for many other environmental and human-health concerns12. Modern integrated pest management is trending towards reducing reliance on chemical insecticides in favour of other environmentally friendly management techniques to reduce the emergence of resistances10,13.

Genetic biocontrol, defined as the release of organisms which have been genetically altered to reduce the spread and harm caused by a target species14, is one such alternative that’s been gaining broader public acceptance15. Early and well established genetic biocontrol technologies (GBT) such as the sterile insect technique (SIT) involve the release of mass numbers of males which have been radiologically sterilised16, thereby reducing the reproductive potential of the females. More modern GBT, such as the release of insects carrying a dominant lethal gene (RIDL)17 and gene drives18 function by propagating transgenes which reduce the fitness of future generations as the transgenes are inherited. Cage and field trials of these second-generation GBT have begun to demonstrate their improved efficacy19,20,21, requiring fewer released males compared to conventional approaches to achieve similar population control, albeit with a potential trade-off between enhanced efficacy and reduced control over the degree of transgene introgression14.

Currently, all GBT require a minimum of a generation to take effect on the target population and often much longer until the harm from a pest outbreak is mitigated19. While this generational lag period is less problematic for species where immature life stages are the primary cause of harm, it poses a significant challenge for many disease vectors and agricultural pests where adult females are the main concern. For example, wild female Ae. aegypti have a median adult lifespan of 2–3 weeks22,23, will typically mate within 24–48 h of emerging24, and on average will take 0.63–0.76 blood meals per day25. Females that mate with GBT males may not produce viable offspring, but they can continue to spread disease or damage crops. Although current GBT are highly effective at intergenerational population control, a more rapid response to outbreaks of disease vectors is critical to mitigate the spread of arboviruses and avert the risk of epidemics, particularly in regions with seasonal population dynamics26.

An alternative approach to GBT that has been speculated on is utilising seminal fluid proteins (SFP) as a target to affect the fitness or fertility of mated females27,28,29,30. SFPs are produced within the male accessory glands (MAG) and stored within the lumen until they are transferred to females along with sperm and other compounds. SFPs such as ovulin (Acp26Aa) and sex peptides are known to generate various post-mating responses and physiological changes in females, such as reduced mating receptivity and median lifespan31,32. It has been demonstrated in Drosophila melanogaster that several low molecular weight SFP can pass through the female reproductive tract and enter the circulatory system (haemolymph), and even to act on receptors in the central nervous system (CNS)33,34. Evidence is mounting that mosquito SFP also act on receptors found within the CNS, with 30% of radiolabelled Culex SFP localising to the female head and thorax35, and intra-thoracic but not intra-abdominal SFP injections resulting in mating refractoriness in Anopheline and Aedes females36,37,38,39.

Here we describe the toxic male technique (TMT), which is—to the best of our knowledge—the first example of an intragenerational GBT. By genetically engineering pest species to express toxic, low molecular weight compounds within the MAG, the survival of mated females can be reduced (Fig. 1). Using D. melanogaster as a proof of concept, we engineer males to express one of seven insect-specific venom proteins in a MAG-specific pattern. Of the >1600 characterised venom compounds, 60% of these are cysteine-knotted mini-proteins40, which range from 2.6 to 14.8 kDa and are highly stable, taxonomically selective and less susceptible to pore region mutations associated with insecticide resistances41. Like endogenous SFP, the recombinant venom peptides should remain safely sequestered within the lumen of the MAG and not enter the male’s haemolymph. If the recombinant venom peptides pass through the mated female’s reproductive tract to affect the target ion channel receptors in her CNS, the neurotoxic effects are likely to be fast-acting and dose-dependent.

Current mating-based methods of genetic biocontrol (A) function by affecting the viability or sex ratio of the offspring of subsequent generations. However, mated females persist in the target area and can continue to cause harm (e.g. spread disease). Intragenerational biocontrol (B), such as TMT, directly affects the fitness of mated females, thereby rapidly reducing the harm caused by the target population. Created in BioRender. Maselko, M. (2024) https://BioRender.com/r25q201.

The median lifespans of wild-type females mated to two of the TMT strains are reduced by 37–64% after initial exposure compared to control females mated to wild-type males. Single-pair mating assays find that TMT males are able to court wild-type females as effectively as wild-type males. MAG-specific expression of a 5.2 kDa venom peptide has no significant effect on the lifespan of adult TMT males, but expression of a 2.9 kDa venom peptide reduces lifespan by 59% compared to wildtype and transgenic controls. To determine the theoretical capability of TMT to suppress a pest population in comparison to female-specific RIDL (fsRIDL), the current state-of-the-art GBT, we develop an agent-based model to simulate an idealised Ae. aegypti release programme19. Sensitivity analysis of the model found that the improved performance of TMT compared to fsRIDL is consistent across a broad range of values of polyandry, density-dependent mortality, and release ratios, with TMT reducing blood feeding rates by a further 40–60% in most simulations. These results demonstrate the potential of TMT as the next generation of genetic biocontrol, which is especially suited to rapidly respond to outbreaks of disease vectors and agricultural pests.

References

-

World Health Organization. World malaria report 2023. (2023)

-

Roiz, D. et al. Integrated Aedes management for the control of Aedes-borne diseases. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 12, e0006845 (2018).

-

Wilder-Smith, A. et al. Epidemic arboviral diseases: priorities for research and public health. Lancet Infect. Dis. 17, e101–e106 (2017).

-

Diagne, C. et al. High and rising economic costs of biological invasions worldwide. Nature592, 571–576 (2021).

-

Bacher, S. et al. Impacts of invasive alien species on nature, nature’s contributions to people, and good quality of life. In Thematic Assessment Report on Invasive Alien Species and their Control of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. (eds. Roy, H. E., Pauchard, A., Stoett, P. & Renard Truong, T.) Ch. 4 (Zenodo, 2023). https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7430731.

-

Leroy, B. et al. Analysing economic costs of invasive alien species with the invacost r package. Methods Ecol. Evol. 13, 1930–1937 (2022).

-

Savary, S. et al. The global burden of pathogens and pests on major food crops. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 3, 430–439 (2019).

-

Howe, L. et al. Malaria parasites (Plasmodium spp.) infecting introduced, native and endemic New Zealand birds. Parasitol. Res. 110, 913–923 (2012).

-

van Riper, III C., van Riper, S. G., Goff, M. L. & Laird, M. The epizootiology and ecological significance of malaria in Hawaiian land birds. Ecol. Monogr. 56, 327–344 (1986).

-

World Health Organization. Test Procedures for Insecticide Resistance Monitoring in Malaria Vector Mosquitoes (World Health Organization, 2013).

-

Liu, N. Insecticide resistance in mosquitoes: impact, mechanisms, and research directions. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 60, 537–559 (2015).

-

Ansari, M. S., Moraiet, M. A. & Ahmad, S. In Environmental Deterioration and Human Health(eds. Malik, A., Grohmann, E. & Akhtar, R.) Ch. 6 (Springer, 2014).

-

Bueno, A. F. et al. Challenges for adoption of integrated pest management (IPM): the soybean example. Neotrop. Entomol. 50, 5–20 (2021).

-

Teem, J. L. et al. Genetic biocontrol for invasive species. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 8, 452 (2020).

-

Winneg, K. M., Stryker, J. E., Romer, D. & Jamieson, K. H. Differences between Florida and the rest of the United States in response to local transmission of the zika virus: implications for future communication campaigns. Risk Anal. 38, 2546–2560 (2018).

-

Knipling, E. F. Possibilities of insect control or eradication through the use of sexually sterile males. J. Econ. Entomol. 48, 459–462 (1955).

-

Fu, G. et al. Female-specific insect lethality engineered using alternative splicing. Nat. Biotechnol. 25, 353–357 (2007).

-

Esvelt, K. M., Smidler, A. L., Catteruccia, F. & Church, G. M. Concerning RNA-guided gene drives for the alteration of wild populations. eLife 3, e03401 (2014).

-

Carvalho, D. O. et al. Suppression of a field population of Aedes aegypti in Brazil by sustained release of transgenic male mosquitoes. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 9, e0003864 (2015).

-

Shelton, A. M. et al. First field release of a genetically engineered, self-limiting agricultural pest insect: evaluating its potential for future crop protection. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 7, 482 (2020).

-

Hammond, A. et al. Gene-drive suppression of mosquito populations in large cages as a bridge between lab and field. Nat. Commun. 12, 4589 (2021).

-

Sheppard, P. M., Macdonald, W. W., Tonn, R. J. & Grab, B. The dynamics of an adult population of Aedes aegypti in relation to dengue haemorrhagic fever in Bangkok. J. Anim. Ecol. 38, 661–702 (1969).

-

Sowilem, M. M., Kamal, H. A. & Khater, E. I. Life table characteristics of Aedes aegypti(Diptera: Culicidae) from Saudi Arabia. Trop. Biomed. 30, 301–314 (2013).

-

Ramírez-Sánchez, L. F., Hernández, B. J., Guzmán, P. A., Alfonso-Parra, C. & Avila, F. W. The effects of female age on blood-feeding, insemination, sperm storage, and fertility in the dengue vector mosquito Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae). J. Insect Physiol. 150, 104570 (2023).

-

Scott, T. W. et al. Longitudinal Studies of Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) in Thailand and Puerto Rico: blood feeding frequency. J. Med. Entomol. 37, 89–101 (2000).

-

Weaver, S. C. Prediction and prevention of urban arbovirus epidemics: a challenge for the global virology community. Antivir. Res. 156, 80–84 (2018).

-

Alfonso-Parra, C. et al. Synthesis, depletion and cell-type expression of a protein from the male accessory glands of the dengue vector mosquito Aedes aegypti. J. Insect Physiol. 70, 117–124 (2014).

-

Marshall, J. M., Pittman, G. W., Buchman, A. B. & Hay, B. A. Semele: a killer-male, rescue-female system for suppression and replacement of insect disease vector populations. Genetics 187, 535–551 (2011).

-

Hurtado, J., Revale, S. & Matzkin, L. M. Propagation of seminal toxins through binary expression gene drives could suppress populations. Sci. Rep. 12, 6332 (2022).

-

Sirot, L. K. et al. Identity and transfer of male reproductive gland proteins of the dengue vector mosquito, Aedes aegypti: potential tools for control of female feeding and reproduction. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 38, 176–189 (2008).

-

Chapman, T., Liddle, L. F., Kalb, J. M., Wolfner, M. F. & Partridge, L. Cost of mating in Drosophila melanogaster females is mediated by male accessory gland products. Nature373, 241–244 (1995).

-

Avila, F. W., Sirot, L. K., LaFlamme, B. A., Rubinstein, C. D. & Wolfner, M. F. Insect seminal fluid proteins: identification and function. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 56, 21–40 (2011).

-

Lung, O. & Wolfner, M. F. Drosophila seminal fluid proteins enter the circulatory system of the mated female fly by crossing the posterior vaginal wall. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 29, 1043–1052 (1999).

-

Yapici, N., Kim, Y.-J., Ribeiro, C. & Dickson, B. J. A receptor that mediates the post-mating switch in Drosophila reproductive behaviour. Nature 451, 33–37 (2008).

-

Young, A. D. M. & Downe, A. E. R. Male accessory gland substances and the control of sexual receptivity in female Culex tarsalis. Physiol. Entomol. 12, 233–239 (1987).

-

Klowden, M. J. Sexual receptivity in Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes: absence of control by male accessory gland substances. J. Insect Physiol. 47, 661–666 (2001).

-

Shutt, B., Stables, L., Aboagye-Antwi, F., Moran, J. & Tripet, F. Male accessory gland proteins induce female monogamy in anopheline mosquitoes. Med. Vet. Entomol. 24, 91–94 (2010).

-

Helinski, M. E. H., Deewatthanawong, P., Sirot, L. K., Wolfner, M. F. & Harrington, L. C. Duration and dose-dependency of female sexual receptivity responses to seminal fluid proteins in Aedes albopictus and Ae. aegypti mosquitoes. J. Insect Physiol. 58, 1307–1313 (2012).

-

Duvall, L. B., Basrur, N. S., Molina, H., McMeniman, C. J. & Vosshall, L. B. A peptide signaling system that rapidly enforces paternity in the Aedes aegypti mosquito. Curr. Biol. 27, 3734–3742.e5 (2017).

-

Kuhn-Nentwig, L., Stöcklin, R. & Nentwig, W. Venom composition and strategies in spiders. Adv. Insect Physiol. 40, 1–86 (2011).

-

King, G. F. Tying pest insects in knots: the deployment of spider‐venom‐derived knottins as bioinsecticides. Pest Manag. Sci. 75, 2437–2445 (2019).

-

Leader, D. P., Krause, S. A., Pandit, A., Davies, S. A. & Dow, J. A. T. FlyAtlas 2: a new version of the Drosophila melanogaster expression atlas with RNA-Seq, miRNA-Seq and sex-specific data. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, D809–D815 (2018).

-

Ishikawa, T. et al. DCRY is a Drosophila photoreceptor protein implicated in light entrainment of circadian rhythm. Genes Cells 4, 57–65 (1999).

-

Lee, P.-T. et al. A gene-specific T2A-GAL4 library for Drosophila. eLife 7, e35574 (2018).

-

Yoffe, K. B., Manoukian, A. S., Wilder, E. L., Brand, A. H. & Perrimon, N. Evidence for engrailed-independent wingless autoregulation in Drosophila. Dev. Biol. 170, 636–650 (1995).

-

Chapman, T. et al. The sex peptide of Drosophila melanogaster: female post-mating responses analyzed by using RNA interference. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100, 9923–9928 (2003).

-

Shearin, H. K., Macdonald, I. S., Spector, L. P. & Stowers, R. S. Hexameric GFP and mCherry reporters for the Drosophila GAL4, Q, and LexA transcription systems. Genetics 196, 951–960 (2014).

-

Manning, A. The control of sexual receptivity in female Drosophila. Anim. Behav. 15, 239–250 (1967).

-

Manning, A. A sperm factor affecting the receptivity of Drosophila melanogaster females. Nature 194, 252–253 (1962).

-

Proverbs, M. D., Newton, J. R. & Campbell, C. J. Codling moth: a pilot program of control by sterile insect release in British Columbia. Can. Entomol. 114, 363–376 (1982).

-

Wee, S. L. et al. Effects of substerilizing doses of gamma radiation on adult longevity and level of inherited sterility in Teia anartoides (Lepidoptera: Lymantriidae). J. Econ. Entomol.98, 732–738 (2005).

-

Edward, D. A., Fricke, C., Gerrard, D. T. & Chapman, T. Quantifying the life‐history response to increased male exposure in female Drosophila melanogaster. Evolution 65, 564–573 (2011).

-

Von Philipsborn, A. C., Shohat-Ophir, G. & Rezaval, C. Single-pair courtship and competition assays in Drosophila. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2023, pdb.prot108105 (2023).

-

Ling, J. et al. A nanobody that recognizes a 14-residue peptide epitope in the E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme UBC6e modulates its activity. Mol. Immunol. 114, 513–523 (2019).

-

Degner, E. C. & Harrington, L. C. Polyandry depends on postmating time interval in the dengue vector Aedes aegypti. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 94, 780–785 (2016).

-

Harrington, L. C. et al. Heterogeneous feeding patterns of the dengue vector, Aedes aegypti, on individual human hosts in rural Thailand. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 8, e3048 (2014).

-

Chan, M. & Johansson, M. A. The incubation periods of dengue viruses. PLoS ONE 7, e50972 (2012).

-

ten Broeke, G., van Voorn, G. & Ligtenberg, A. Which sensitivity analysis method should I use for my agent-based model? JASSS 19, 5 (2016).

-

Quistad, G. B., Dennis, P. A. & Skinner, W. S. Insecticidal activity of spider (Araneae), centipede (Chilopoda), scorpion (Scorpionida), and snake (Serpentes) venoms. J. Econ. Entomol. 85, 33–39 (1992).

-

Schwartz, E. F., Mourão, C. B. F., Moreira, K. G., Camargos, T. S. & Mortari, M. R. Arthropod venoms: a vast arsenal of insecticidal neuropeptides. Pept. Sci. 98, 385–405 (2012).

-

Guo, S., Herzig, V. & King, G. F. Dipteran toxicity assays for determining the oral insecticidal activity of venoms and toxins. Toxicon 150, 297–303 (2018).

-

Oh, R. J. Repeated copulation in the brown planthopper, Nilaparvata lugens Stál (Homoptera; Delphacidae). Ecol. Entomol. 4, 345–353 (1979).

-

Cabauatan, P. Q., Cabunagan, R. C. & Choi, I.-R. In Planthoppers: New Threats to the Sustainability of Intensive Rice Production Systems in Asia (eds. Heong, K. L. & Hardy, B.) 357–368 (International Rice Research Institute, 2009).

-

Denecke, S., Swevers, L., Douris, V. & Vontas, J. How do oral insecticidal compounds cross the insect midgut epithelium. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 103, 22–35 (2018).

-

Kandul, N. P. et al. Transforming insect population control with precision guided sterile males with demonstration in flies. Nat. Commun. 10, 84 (2019).

-

Massonnet-Bruneel, B. et al. Fitness of transgenic mosquito Aedes aegypti males carrying a dominant lethal genetic system. PLoS ONE 8, e62711 (2013).

-

Upadhyay, A. et al. Genetically engineered insects with sex-selection and genetic incompatibility enable population suppression. eLife 11, e71230 (2022).

-

Ejima, A. & Griffith, L. C. Measurement of courtship behavior in Drosophila melanogaster. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2007, pdb.prot4847 (2007).

-

Mueller, J. L., Linklater, J. R., Ravi Ram, K., Chapman, T. & Wolfner, M. F. Targeted gene deletion and phenotypic analysis of the Drosophila melanogaster seminal fluid protease inhibitor Acp62F. Genetics 178, 1605–1614 (2008).

-

Zhang, S. D. & Odenwald, W. F. Misexpression of the white (w) gene triggers male-male courtship in Drosophila. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 92, 5525–5529 (1995).

-

Sirot, L. K., Buehner, N. A., Fiumera, A. C. & Wolfner, M. F. Seminal fluid protein depletion and replenishment in the fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster: an ELISA-based method for tracking individual ejaculates. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 63, 1505–1513 (2009).

-

Maselko, M. & Beach, S. Plasmid sequences for: Recombinant venom proteins in insect seminal fluid reduces female lifespan. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13910640(2024).

-

Joiner, M. A. & Griffith, L. C. Visual input regulates circuit configuration in courtship conditioning of Drosophila melanogaster. Learn. Mem. 7, 32–42 (2000).

-

Hegde, R., Hegde, S., Gataraddi, S., Kulkarni, S. S. & Gai, P. B. Novel and PCR ready rapid DNA isolation from Drosophila. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids 41, 1162–1173 (2022).

-

Sauers, L. A., Hawes, K. E. & Juliano, S. A. Non-linear relationships between density and demographic traits in three Aedes species. Sci. Rep. 12, 8075 (2022).

-

Goindin, D., Delannay, C., Ramdini, C., Gustave, J. & Fouque, F. Parity and longevity of Aedes aegypti according to temperatures in controlled conditions and consequences on dengue transmission risks. PLoS ONE 10, e0135489 (2015).

-

Christophers, A. A. The yellow fever mosquito, its life history, bionomics and structure. J. Natl Med. Assoc. 54, 132 (1960).

-

Almeida, S. J. D., Martins Ferreira, R. P., Eiras, Á. E., Obermayr, R. P. & Geier, M. Multi-agent modeling and simulation of an Aedes aegypti mosquito population. Environ. Model. Softw.25, 1490–1507 (2010).

-

Maneerat, S. & Daudé, E. A spatial agent-based simulation model of the dengue vector Aedes aegypti to explore its population dynamics in urban areas. Ecol. Model. 333, 66–78 (2016).

-

Pimid, M. et al. Parentage assignment using microsatellites reveals multiple mating in Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae): implications for mating dynamics. J. Med. Entomol. 59, 1525–1533 (2022).

-

Seabold, S. & Perktold, J. Statsmodels: econometric and statistical modeling with Python. In Proc. 9th Python in Science Conference 92–96 (2010).

-

Herman, J. & Usher, W. SALib: an open-source Python library for sensitivity analysis. J. Open Source Softw. 2, 97 (2017).

-

Pedregosa, F. et al. Scikit-learn: machine learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 12, 2825–2830 (2011).

-

Davidson-Pilon, C. lifelines: survival analysis in Python. J. Open Source Softw. 4, 1317 (2019).

-

Hunter, J. D. Matplotlib: a 2D graphics environment. Comput. Sci. Eng. 9, 90–95 (2007).

-

Waskom, M. L. seaborn: statistical data visualization. J. Open Source Softw. 6, 3021 (2021).

-

Maselko, M. & Beach, S. J. Data and code for: recombinant venom proteins in insect seminal fluid reduces female lifespan. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13927099 (2024).

-

MaselkoLab. TMT-Aedes-model. GitHub (2024).