The climate case for cheap food

An analysis of diets worldwide reveals that lower-cost diets are often substantially less carbon-intensive than the meals people eat most often.

By Emma Bryce in Anthropocene

From: Environmental impacts and monetary costs of healthy diets worldwide

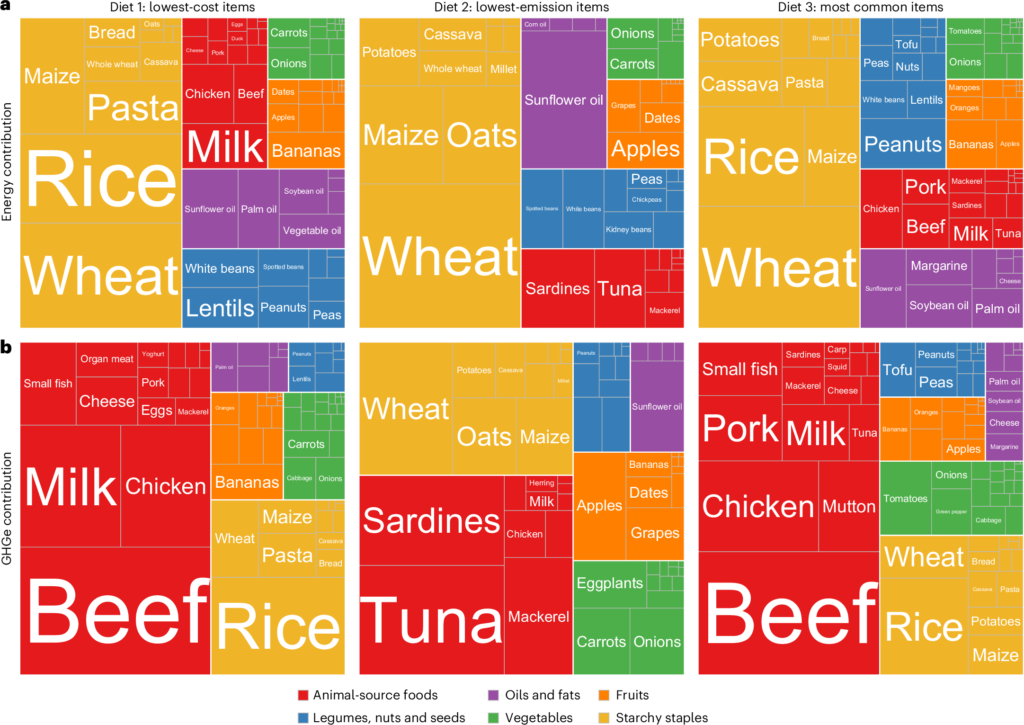

a, Dietary energy shares of food items are colour coded in each of six HDB food groups: animal-source foods; starchy staples; legumes, nuts and seeds; vegetables; fruits; and oils and fats. b, Shares of GHG-equivalent (GHGe) emissions are shown for each item in the same food groups. Both sets of results are shown for three extreme benchmark diet scenarios: diet 1 (lowest-cost items), diet 2 (lowest-emission items) and diet 3 (most common items) in each country. Data shown are from 171 countries for diets 1 and 2 and 159 countries for diet 3.

People can eat sustainably and protect their wallets at the same time: in fact a new study that drew on data from almost every country finds that diets which are good for people and the planet are typically some of the cheapest, too.

That challenges assumptions that sustainable diets are by default more expensive, the researchers say.

For the study, they gathered dietary data from 171 countries, calculating the economic costs and greenhouse gas impacts of locally-available foods in each case. The researchers then took a diet of the most commonly-consumed foods in each country, and compared it with other hypothetical diets, made up of from the same array of local foods, but tweaked to focus on lowering greenhouse gas emissions, or reducing costs.

Their modeling showed that consuming diets made up of the most common foods across the globe would generate 2.44 kilograms of CO2-equivalent per person each day, and cost an average $9.96. Compared to that, national diets designed to have the lowest greenhouse gas emissions and still meet nutritional demands in each case would slash daily per capita global emissions to an average 0.67 kgCO2e.

Then, when the researchers tried to balance health with low cost by developing nutritional diets that used the least expensive foods in each country, they found this would cost just $3.68 per person per day on average—three times less than the default diet made of the most consumed foods.

The economic impact of plant-based diets: fewer jobs, lower costs, and big climate benefits

More interestingly, this healthy, economical diet was also more sustainable, generating an average 1.65 kgCO2e per person per day. While that’s higher than diets designed purely to reduce emissions, it’s a third less than the default common food diet—and suggests that sustainable food can be an affordable choice.

This study trades on the fact that there is enough variety within dietary food groups that we are able to swap out pricier, higher-impact foods for lower-impact options that are just as nutritious. As a general rule this means that “choosing less expensive options in each food group is a reliable way to lower the climate footprint of one’s diet,” the researchers say.

There were some interesting exceptions. In many countries dairy milk is the cheapest and most nutritious of animal-sourced foods, and yet it produces substantial emissions. Foods like mackerel and sardines in these countries would have lower emissions per calorie and are a similarly nutritious substitute—but would be slightly pricier, the researchers found.

Likewise, rice is one of the cheapest grains globally, but the way it’s farmed produces large amounts of methane. Wheat and barley, meanwhile, cost a little more but produce much less in the way of greenhouse gas.

But overall, the logic holds: it’s possible to eat on a budget and do your bit for the planet, according to the research: “At the grocery store, frugality is a helpful guide to sustainability.”

Bai et. al. “Environmental impacts and monetary costs of healthy diets worldwide.” Nature Food. 2025.

How to understand the figure:

Figure 4 uses a mosaic plot with rectangles proportional to dietary energy and GHG emissions from each item, colour coded by food group, in the global average of three benchmark healthy diets using only the lowest-cost items (diet 1), the lowest-emission items (diet 2) and the most commonly consumed items (diet 3). Some items make large energy contributions in all three diet scenarios, indicating that they are consistently inexpensive and commonly consumed and have low emissions, notably wheat, maize, white beans, apples, onions and carrots. Other foods are inexpensive and commonly consumed but have higher emissions than other options in the same food group, such as rice, pasta, palm oil, milk, chicken and beef. A third category of food items, such as oats and sardines, often have the lowest emissions in their food group but are neither the least expensive nor the most commonly consumed options. As shown in Figs. 1 and 2, the lowest-emission items generally also have lower cost per day than other commonly consumed items in their food group. The largest trade-offs shown in Fig. 4 are for starchy staples, because rice is inexpensive and widely consumed in large quantities with higher emissions (averaging 2.19 kgCO2e) compared with wheat (0.57 kgCO2e) and maize (0.48 kgCO2e). By contrast, oats have relatively low average emissions (0.67 kgCO2e) but are almost never either the lowest-cost or the most widely consumed starchy staple.

Item selection is based only on food group targets specified in the HDB (Healthy Diet Basket) derived from national dietary guidelines, so the resulting mix of foods also generally meets all essential nutrient requirements as measured by mean adequacy ratios around 0.95 across diets. Minor shortfalls are observed for calcium, vitamin C, riboflavin and vitamin B12 in diet 1; vitamin C, riboflavin and calcium in diet 2; and calcium, riboflavin, vitamin B12 and vitamin A in diet 3. These gaps may partly reflect the use of national average food price data and nutrient composition values primarily from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) database, but they highlight nutrients that could warrant attention when designing cost-effective, low-emission diets (Supplementary Table 7).