The perverse dilemma of reef recovery: Less fish now, more food later.

Scientists say coral fisheries could sustainably provide thousands of additional meals per square kilometer. But it requires sacrifice from communities that already have little to spare.

January 7, 2026

Coral reefs are the breadbaskets of the ocean, home to an outsized amount of the fish that wind up on people’s plates.

But reefs could be producing a lot more food. With careful management, these places could generate enough additional fish to feed millions more people, many in places wracked with malnutrition, according to new research in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The results “reinforce that effective reef fisheries monitoring and management has substantial and measurable benefits beyond environmental conservation; it has food security and public health implications,” said Jessica Zamborain-Mason, the lead author and a marine scientist at the King Abdullah University of Science and Technology in Saudi Arabia.

effective reef fisheries monitoring and management has substantial and measurable benefits beyond environmental conservation; it has food security and public health implications

But it will be no easy task making good on this promise. Coral reefs are being buffeted by underwater heat waves, with scientists warning climate change threatens much of the world’s coral. Many of these reefs have little oversight, so regulatory infrastructure such as scientists and managers is lacking. Perhaps most daunting is the difficulty of restricting fishing in places where people rely on it to survive day-to-day.

“If you’re going to reduce fishing pressure to give yourself more fish protein in the long run on a sustainable basis, you need some way to meet the nutritional shortfall in the short term. I think that’s the biggest challenge,” said Sean Connolly, an ecologist at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute who worked on the study.

To estimate the gap between what reefs produce today and what they could produce, the scientists built a model of fisheries productivity at reefs around the world. It relied on sampling done at more than 2,000 sites. Of those, 150 were protected or remote, uninhabited reefs, providing a reference point for how many fish would be at a particular kind of reef if it weren’t subject to fishing.

To determine the maximum amount of fish that could be harvested from these reefs if they were sustainably managed, the scientists adopted a widely-used metric that fishers should take no more than half the total biomass of what would be found in an untouched reef. If the biomass fell below that 50% benchmark, it was overfished.

Trying to save coral reefs? Think like a hedge fund manager.

The calculation revealed a yawning gap in many places between how much fish should be in the water in a well-managed fishery, and how many fish were actually there. In the most extreme cases, less than 10% of fish biomass was found on reefs in Kenya, Mauritius and Oman. But they weren’t alone. Overfished reefs globally had a 32% fish deficit compared to what could be swimming there if the reefs were fished to maximum level while still remaining sustainable, the scientists reported.

The work “quantifies how much is being lost by having overfished reef fish communities in terms of food provisioning and, in turn, how much could be gained from rebuilding reef fish stocks and managing them at sustainable levels,” said Zamborain-Mason.

If all those fisheries were allowed to recover, the additional fish would translate into a staggering 9,000 extra meals for every square kilometer of coral reef, the scientists found. Much of the benefit would come in the developing world, in countries with high levels of hunger. In Indonesia, an additional 1.4 million people would get the recommended amount of fish in their diet. In the Philippines it would meet the needs of more than 800,000. More than 500,000 Tanzanians would experience similar gains.

“Countries with higher malnutrition indexes could benefit more from recovered reef fish stocks,” said Connolly.

But it would take years of careful management, and disruptions to people’s current ways of life, to translate these calculations into reality. With the most draconian regulations – a ban on fishing – the median time to recovery for a reef would be 6 years. A more measured approach, by contrast, would take nearly half a century for the median fishery. Some of the most battered places could take up to 70 years. And that’s without accounting for how habitat loss from dying coral might diminish fish productivity.

Such measures could require wrenching changes in people’s way of life. While the scientists don’t spell out detailed reforms, they note that fishing reductions would have to be paired with alternative food production such as farming. In the cases of small islands with little available land, it could require finding other seafood or importing food from abroad.

In other words, making reef fisheries both more sustainable and more productive sounds appealing. Making it happen could be very hard.

Zamborain-Mason, et. al. “Potential yield and food provisioning gains from rebuilding the world’s coral reef fish stocks.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Dec. 16, 2025.

AI summary of article

The study by Zamborain-Mason et al. in PNAS (Dec 2025) reveals that rebuilding depleted coral reef fish stocks could boost sustainable yields by nearly 50%, offering millions of extra seafood servings, particularly benefiting food-insecure regions with high malnutrition. Reaching these gains requires fish biomass to double, potentially adding 20,000 to 162 million servings annually in some areas, but faces challenges from climate change and implementation hurdles for local management.

Key Findings

- Significant Yield Increase: Global coral reefs could produce almost 50% more sustainable fish if stocks recover to maximum production levels.

- Food Security Boost: This recovery could provide millions of people with recommended daily seafood intake, especially in countries with high hunger rates, like parts of Africa and Southeast Asia.

- Biomass Requirement: Achieving these benefits means fish stocks generally need to double their current standing biomass (around 32 tonnes/km²).

- Benefits for Vulnerable Nations: The greatest potential gains in servings correlate with higher global hunger indexes, highlighting benefits for food-insecure nations.

Challenges & Context

- Climate Change: Heatwaves threaten coral reefs, complicating recovery efforts.

- Management Gaps: Implementing effective local fisheries management, including monitoring and restrictions, is difficult where people rely on daily fishing for survival.

- “Less Now, More Later” Dilemma: Recovery requires temporarily reducing fishing (restricting fishing now) to build stocks, a tough choice for communities needing immediate food.

Significance

The research emphasizes that effective reef management offers significant food security and public health benefits, not just environmental ones, suggesting a dual approach of local management alongside global climate action.

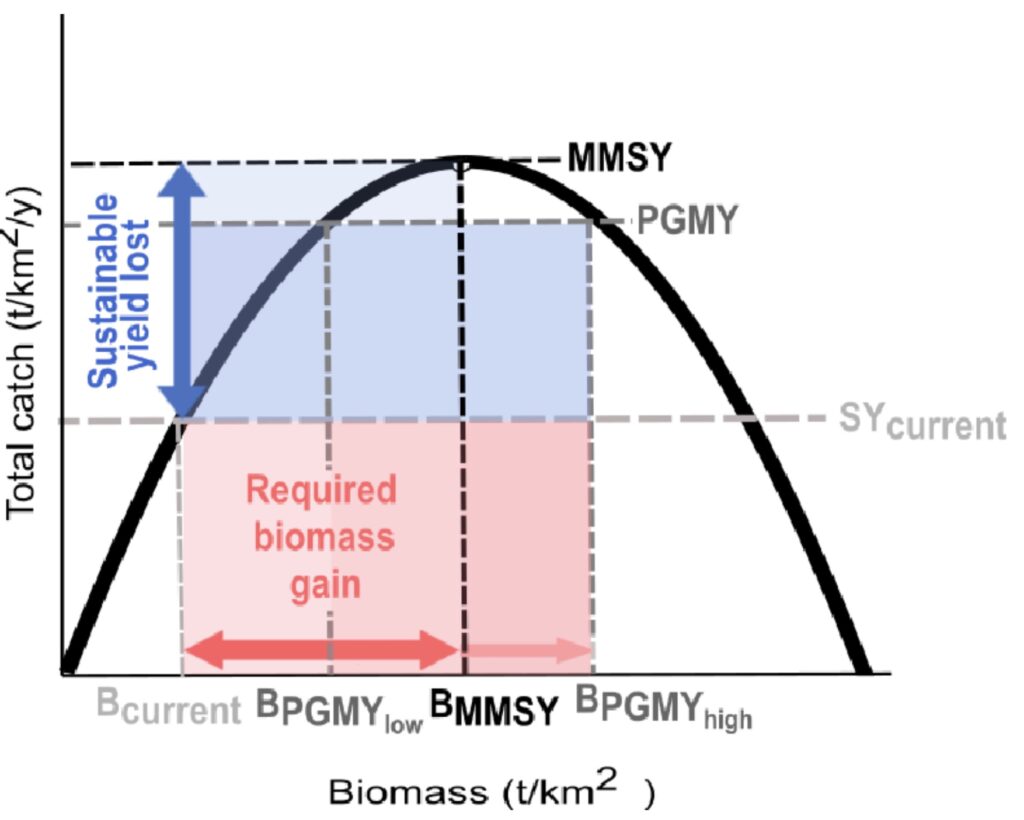

Figure 1| Theoretical relationship between sustainable yield losses and required biomass 116 gains in coral reef fisheries. Conceptual surplus production curve diagram exemplifying how to quantify (i) the sustainable yield lost from having fish assemblages below biomass levels aimed at maximizing sustainable production BMMSY (Bcurrent<BMMSY) and (ii) the required biomass increases to recover assemblages to either maximum production values (MMSY) or pretty good multispecies yields (PGMY). The x axis represents the standing fish assemblage biomass and the y axis the sustainable total catch or estimated surplus production for the whole multispecies assemblage. The solid line represents the expected surplus production along a gradient of biomass (assuming a Graham-Schaefer surplus curve for the multispecies assemblage, according to which MMSY is achieved at biomass levels corresponding to 50% of unfished biomass). SYcurrent is the expected long-term yield (i.e., surplus) from a hypothetical multispecies assemblage given its standing biomass (Bcurrent); BMMSY is the estimated biomass at which MMSY is achieved; and BPGMY are the estimated biomass at which PGMY are attained (below and above BMMSY: BPGMY,low and BPGMY,high, respectively). Note that we are not comparing current yields (i.e., how much is being caught on a reef) with potential maximum sustainable yields (i.e., how much could be caught sustainably if managing assemblages to maximize production) but instead how much sustainable yields could increase from their current hypothetical sustainable levels,