The trillions of microbes inhabiting tree bark can suck up planet-warming gases, scientists have discovered.

January 14, 2026

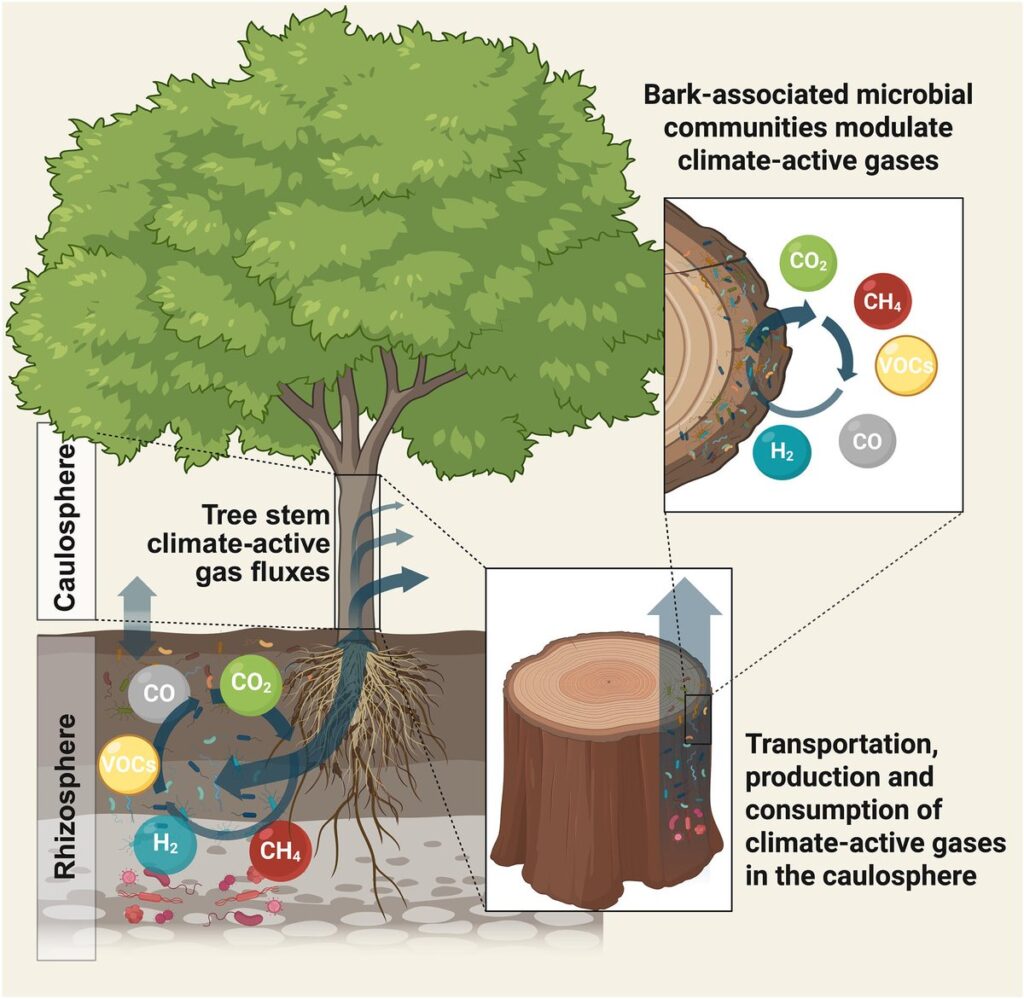

Trees act as conduits linking soils and the atmosphere, facilitating gas exchange and as a niche for microbial communities adapted to metabolizing gas substrates. Together, trees and bark microbiota function as a modulator of the emission and uptake of multiple climate-active gases in forest ecosystems. Original article: Bark microbiota modulate climate-active gas fluxes in Australian forests here: https://lnkd.in/gPTWaWYa

Trees have a well-earned reputation as climate heroes for their ability to suck up carbon dioxide and respire oxygen.

But until now, people have been overlooking tinier but far more numerous parts of the equation: the trillions of bacteria inhabiting tree bark.

Scientists in Australia spent five years peering into the microscopic world of bark, emerging with a description of a place teeming with life, much of it consuming and “exhaling” gases important for the climate. They dubbed it the “barkosphere.”

The numbers alone are staggering. A single square meter of this woody substance can be home to 6 trillion microbes, the scientists reported last week in Science. And there’s enough bark in the world to cover nearly every square meter of land on Earth.

Until recently, trees’ outer skin had been largely ignored. The microbes’ “existence and roles have been overlooked for many decades,” said Pok Man “Bob” Leung, a scientist at Monash University in Australia, who was involved in the new work.

It’s not just the sheer numbers that matter, it’s what they do. “Remarkably, most of these microbes are tree-adapted specialists that feed on climate-active gases,” Leung said.

If you want a fast-growing forest to suck up more carbon, pick slow-growing trees

The researchers discovered this by sampling bark from eight species of Australian trees in a variety of ecosystems, from swamps to upland forests. They then scanned the genetic material collected with the bark to figure out what species of microbes were present, and what the genetic sequences said about their ability to consumer or produce different kinds of gases. They found evidence that many of the bacteria were equipped to extract sustenance from abundant gases including methane, hydrogen and carbon monoxide.

To see how these genetic tools translated into activity, the scientists measured how much of certain gases were consumed and released by bark placed in a special sealed chamber, as well as on sections of trees encased in an airtight shell.

The results revealed that the microbes were consuming gases on an enormous scale. “This microbial activity across this massive ‘bark continent’ is potentially removing millions of tons of climate-active gases every year,” said Luke Jeffrey, a scientist at Southern Cross University who was also part of the research.

The microbes showed the most consistent appetite for hydrogen. Every species tested had microbes that consumed it. Multiply that by the world’s 3 trillion trees, and these little beasts could be sucking up 55 million metric tons of hydrogen every year, the scientists said in a posting at The Conversation.

While hydrogen isn’t directly a greenhouse gas, its presence can slow the breakdown of a methane, a potent climate-warmer. All that hydrogen disappearing into bark could translate to the equivalent of offsetting 15% of human-caused methane emissions each year, the scientists reported.

While people have talked about addressing climate change in part by planting trees, the discovery of this hidden world of bark adds a whole new dimension. It could also inform people’s calculations about which trees are the most potent climate warriors. “We now know different trees host different microbes,” said Chris Greening, a Monash University scientist. “If we can identify the trees with the most active gas-consuming microbes, they could become priority targets for reforestation and urban greening projects.”

Leung, et. al. “Bark microbiota modulate climate-active gas fluxes in Australian forests.” Science. Jan. 8, 2026.

Post: Luke Jeffrey LinkedIn

🚨 Thrilled to share our new research, just published on the cover of the latest issue of Science Magazine!

This paper is one I’ve had the privilege of co–first authoring with the incredibly talented Pok Man LEUNG (aka Bob), alongside Chris Greening, Damien Maher and amazing colleagues and team at Southern Cross University and Monash University.

It represents more than 5-years of collaborative work, from initial ideas and field campaigns through to sequencing, experiments, analyses, and publication!

So what did we find?

Tree bark — usually thought of as an inert, protective layer — is actually a vast and active living interface between forests, the atmosphere, and biodiversity . We discovered that bark hosts abundant, diverse, and highly specialised microbial communities that actively interact with climate-relevant gases 🌳🦠

Across eight common Australian tree species, from hashtag#paperbarks, hashtag#casuarinas and hashtag#mangroves to hashtag#acacias and hashtag#eucalypts, bark contains trillions of microbial cells per square meter. These communities are distinct from soils and water, and uniquely adapted to life on tree surfaces.

Remarkably, many of these microbes use gases such as hashtag#Methane, hashtag#Hydrogen, and hashtag#CarbonMonoxide as energy sources. Our lab and field experiments show that bark microbes can remove multiple greenhouse and trace gases from the atmosphere — with particularly strong uptake and affinity for hydrogen.

Given the immense global surface area of tree bark (comparable to the Earth’s land surface), this points to a previously unrecognised, large-scale atmospheric sink, with meaningful implications for how forests help regulate climate.

At the same time, these systems are dynamic: under low-oxygen conditions inside bark, some microbes may switch to producing methane or hydrogen, highlighting how climate-driven changes like flooding or warming could alter these processes in the future.

This work ultimately reshapes how we think about trees — not just as carbon stores, but as hosts to diverse microbial ecosystems that play an active role in regulating the atmosphere. 🦠🌲🦠 🌳 🦠🌴

Link to the original article: Bark microbiota modulate climate-active gas fluxes in Australian forests here: https://lnkd.in/gPTWaWYa

An accompanying perspective by Vincent Gauci here: https://lnkd.in/g2FdaU2n

The Conversation article here:

https://lnkd.in/gmNgKSbF

Thank you for the funding and support Southern Cross University, Monash University and the Australian Research Council (ARC)