Yes, energy prices are hurting the food sector. But burning more fossil fuels is not the answer

Published: February 4, 2025 in The Conversation

PhD Candidate, Integrated Sustainability Analysis group, University of Sydney

Months out from a federal election, the industry lobby is gearing up in opposition to the Albanese government’s renewable energy targets. In a salvo on Monday, food distributors urged the government to increase fossil fuel production, as a way to purportedly tackle high energy prices.

It was followed by comments on Tuesday by the Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry, which also called for fast-tracking of gas expansion to avoid price spikes and blackouts.

Unfortunately, however, these approaches miss the point. They are a short-sighted response to what is, in large part, a climate-induced problem.

In fact, evidence suggests burning more coal and gas will only make things worse for many industries, including the food sector.

More fossil fuels = more industry disruption

The industry group Independent Food Distributors Australia claims Labor’s energy policies are driving up costs for businesses and, in turn, consumers.

In comments published in The Australian, the group’s chief executive Richard Forbes said the phase-out of coal-fired energy was too fast and the government’s renewable energy target was too ambitious. The newspaper claimed business owners instead want Labor to support new gas plants and support upgrades to existing coal plants.

The group represents food manufacturers, suppliers and distributors supporting the food service industry. Its members largely comprise food distribution warehouses operating large refrigerators and freezers.

Unfortunately, however, these approaches miss the point. They are a short-sighted response to what is, in large part, a climate-induced problem.

First, it’s important to ask whether a focus on renewable energy can be blamed for Australia’s high energy prices. The answer is largely no.

That aside, would expanding fossil fuel production ultimately be a boon to food distributors? Evidence suggests it would not.

A study published in 2022, led by my colleagues at the University of Sydney, found that almost one-fifth of total emissions from global food systems were produced by transport and supporting services, such as distribution warehouses. This was equivalent to about 6% of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions.

Of course, greenhouse gas emissions are warming the climate and leading to worse and more frequent natural disasters. And, as another University of Sydney study showed, these disasters have extensive repercussions for the food industry.

It found the disruptions would be hardest felt by the fruit, vegetable and livestock sectors, however effects flowed to other sectors such as transport services. Overall, people in rural areas and those from a low-socioeconomic background were most vulnerable, both to food and nutrition impacts, as well as losses in employment and income.

What’s more, research I led into the economic impact of Australia’s 2019–20 bushfires also reveals the vulnerability of the food ecosystem. The 2024 study, which focused on tourism, found employment and income losses were greatest in the hospitality and transport sectors respectively. Restaurants, cafes and accommodation providers were disproportionately hit by job losses resulting from reduced consumption, including less food being consumed out of home.

evidence suggests burning more coal and gas will only make things worse for many industries, including the food sector.

So what does all this mean? Clearly, expanding polluting energy generation to reduce food distribution costs in the short term will not, ultimately, secure the sector’s future.

Making food distribution more sustainable

Having said all this, Australia’s high energy prices are undoubtedly a stress point for many Australian businesses. So how can the food sector tackle the problem?

Energy requirements (and therefore costs and emissions) differ according to the type of food. Fruits and vegetables, for example, are likely to require a temperature-controlled environment. This generates about double the emissions produced by growing the crops themselves.

Growing and distributing crops that can be transported at ambient temperatures would reduce energy use. This is particularly important given refrigeration needs are likely to increase as the planet warms.

In terms of broader food movements, 94% of domestic transporthappens by road. So, there is a strong case for investing in electric trucks to help guard against energy price hikes.

The weight of food freight has also been correlated with energy use. Cereals – along with fruit and vegetables, flour and sugar beet/cane – are among the food types transported at high tonnages.

As my colleagues have noted, there are huge energy savings to be gained if the global population ate more locally produced food, and if food businesses used cleaner production and distribution methods, such as natural refrigerants.

Looking ahead

Global food systems are crucial to human wellbeing. It’s in everyone’s interests to keep them functioning well and protected from climate-fuelled hazards.

The choices now facing the food-distribution sector represent one of many tradeoffs Australia must make during its transition to a low-carbon future.

Will we continue the polluting, business-as-usual approach or will we embrace Australia’s natural advantages in renewable energy, and protect the planet that supports us?

When it comes to food distribution, will Australia expand gas and coal production as a purported answer to lower energy costs in the short term – or will we move swiftly to decarbonise the sector and buy more local, sustainable food?

REAL ASSETS

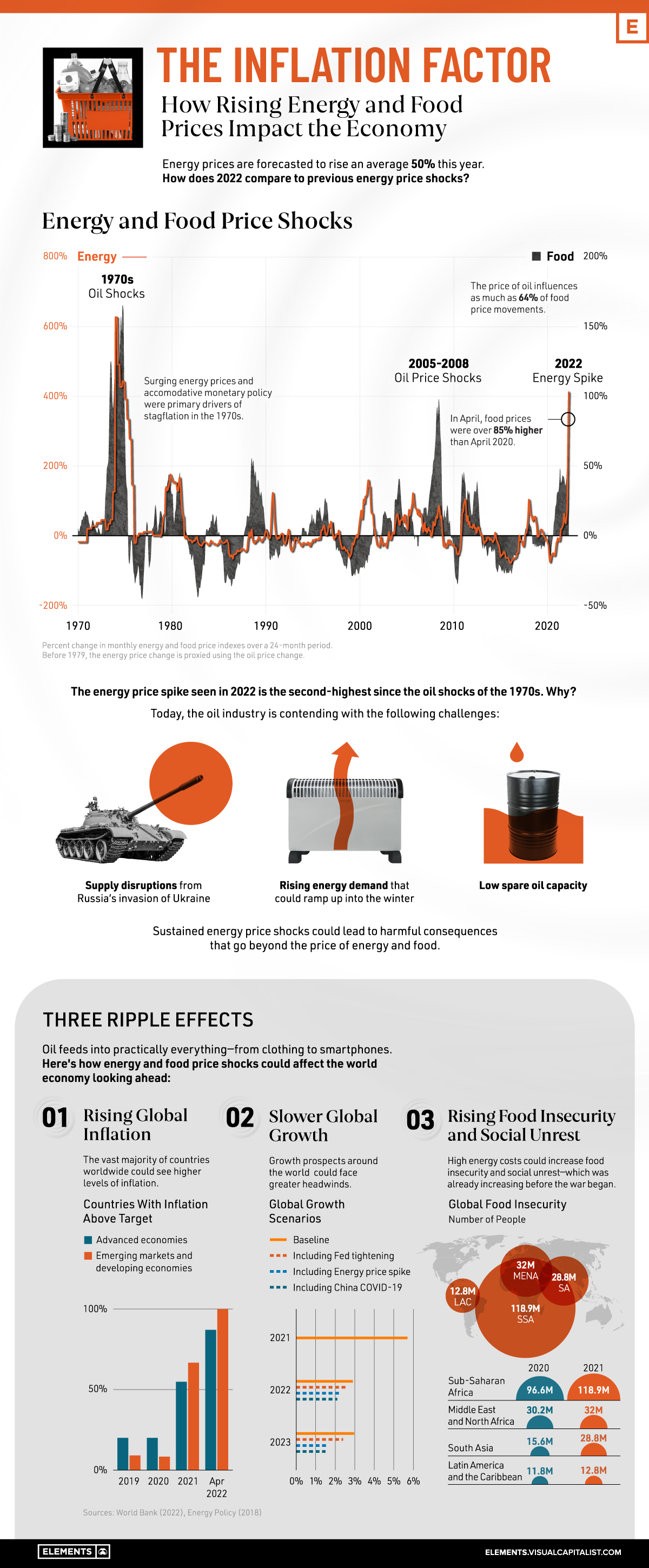

The Inflation Factor: How Rising Food and Energy Prices Impact the Economy

How Rising Food and Energy Prices Impact the Economy

Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the effects of energy supply disruptions are cascading across everything from food prices to electricity to consumer sentiment.

In response to soaring prices, many OECD countries are tapping into their strategic petroleum reserves. In fact, since March, the U.S. has sold a record one million barrels of oil per day from these reserves. This, among other factors, has led gasoline prices to fall more recently—yet deficits could follow into 2023, causing prices to increase.

With data from the World Bank, the above infographic charts energy shocks over the last half century and what this means for the global economy looking ahead.

Energy Price Shocks Since 1979

How does today’s energy price shock compare to previous spikes in real terms?

| U.S.$/bbl Equivalent | Crude Oil | Natural Gas | Coal |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2022* | $93 | $170 | $61 |

| 2008 | $127 | $100 | $46 |

| 1979 | $119 | $72 | $33 |

*2022 forecast

As the above table shows, the annual price of crude oil is forecasted to average $93 per barrel equivalent in 2022. By comparison, during the 2008 and 1979 price shocks, crude oil averaged $127 and $119 per barrel, respectively.

What distinguishes the 2022 energy spike is that prices have soared across all fuels. Where price shocks were more or less isolated in the past, many countries such as Germany and the Netherlands are looking to coal to make up for oil supply disruptions. Meanwhile, European natural gas prices have hit record highs.

Food prices have also spiked. Driven by higher input costs across fuel, chemicals, and fertilizer, agriculture commodity prices are forecasted to rise 18% in 2022. Fertilizer prices alone could increase 70% in part due to Russia’s dominance of the global fertilizer market—exporting more than any country worldwide.

What are 3 Ripple Effects of Rising Energy Prices?

Oil feeds into nearly everything, from food to smartphones. In fact, the price of oil influences as much as 64% of food price movements.

How could energy and food shocks affect the world economy in the near future, and why is a lot riding on the price of oil?

1. Rising Global Inflation

In 2022, inflation became a global phenomenon—impacting 100% of advanced countries and 87% of emerging markets and developing economies analyzed by the World Bank.

| Countries With Inflation Above Target | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | Apr 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emerging Markets and Developing Economies | 20% | 20% | 55% | 87% |

| Advanced Economies | 9% | 8% | 67% | 100% |

Sample includes 31 emerging markets and developing economies and 12 advanced economies

By contrast, roughly two-thirds of advanced economies and just over half of emerging markets experienced inflation above target in 2021.

This has contributed to tighter monetary conditions. The table below shows how rising inflation in the U.S. has corresponded with interest rate hikes since the 1980s:

| Date | Core CPI at Beginning of Cycle | Magnitude of Rate Hikes Over Course of Tightening Cycle |

|---|---|---|

| 1979-81 | 9.3% | 9.0 p.p |

| 1983-84 | 4.6% | 3.0 p.p |

| 1986-89 | 3.6% | 4.0 p.p |

| 1994-95 | 2.8% | 3.0 p.p |

| 1999-00 | 2.0% | 1.75 p.p |

| 2004-06 | 1.9% | 4.25 p.p. |

| 2015-19 | 2.1% | 2.25 p.p |

| 2022-23 | 6.4% | 2.75 p.p |

2023 is an estimate based on market expectations of the level of the Fed Funds rate in mid-2023. U.S. Core CPI for 2023 based on latest data available.

In many cases, when the U.S. has rapidly tightened monetary policy in response to price pressures, emerging markets and developing economies have experienced financial crises amid higher borrowing costs.

2. Slower Global Growth

Energy price shocks could add greater headwinds to global growth prospects:

| Global Growth Scenarios | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 5.7% | 2.9% | 3.0% |

| Including Fed tightening | 2.6% | 2.4% | |

| Including Energy price spike | 2.2% | 1.6% | |

| Including China COVID-19 | 2.1% | 1.5% |

Together, price spikes, hawkish monetary policy, and COVID-19 lockdowns in China could negatively impact global growth.

3. Rising Food Insecurity and Social Unrest

Even before the energy price shock of 2022, global food insecurity was increasing due to COVID-19 and mounting inflationary pressures.

| Number of People in Acute Food Insecurity | 2020 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 97M | 119M |

| Middle East and North Africa | 30M | 32M |

| South Asia | 16M | 29M |

| Latin America and the Caribbean | 12M | 13M |

Sustained food shortages and high food prices could send millions into acute food insecurity.

In addition, high fuel and food prices are often correlated with mass protests, political violence, and riots. While Sri Lanka and Peru have already begun to see heightened riots, Turkey and Egypt are also at risk for social unrest as the cost of living accelerates and food insecurity worsens.

Global Challenges

Since World War II, oil price shocks have been a major constraint on economic growth. As the war in Ukraine continues, the outlook for today’s energy market is far from clear as a number of geopolitical factors could sway oil price movements and its corresponding effects.